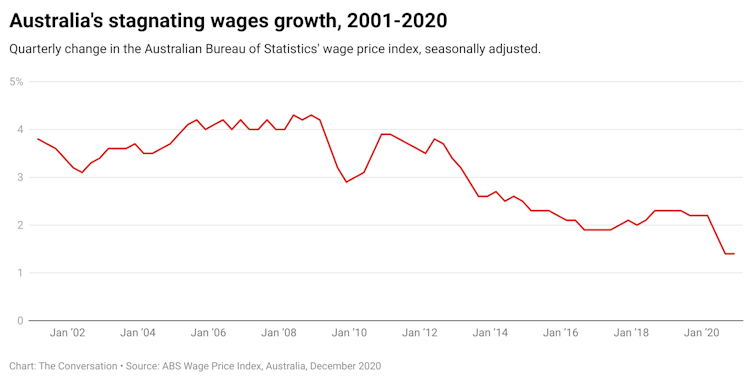

Australia has a serious wage problem. Over the past decade wages for all but the top 20% of income earners have flat-lined.

This is part of the longer-term problem concerning productivity and wages identified by groups like the OECD – namely, workers have not shared in productivity gains, with “labour market flexibility” experiments mostly to blame.

So the decision of the Fair Work Commission – the guardian of what’s left of Australia’s historical approach to ensuring decent pay – to increase the minimum wage by 2.5% is significant.

The commission reviews the minimum wage annually. Last year it granted a 1.7% increase – the lowest in 12 years. This year’s 2.5% is less than the 3.5% wanted by unions, but more than the 1.1% sought by employer groups.

The increase directly affects only about a fifth of Australian employees. It will, however, have indirect benefit for workers earning more, and aid economic renewal.

Higher wages are good for employment

The 2.5% increase is more than what Treasury and the Reserve Bank forecast for average wages over the coming year, but also something these conservative institutions would welcome.

Sluggish wage growth does not just result in greater wage inequality. It effectively retards demand, a key determinant of employment.

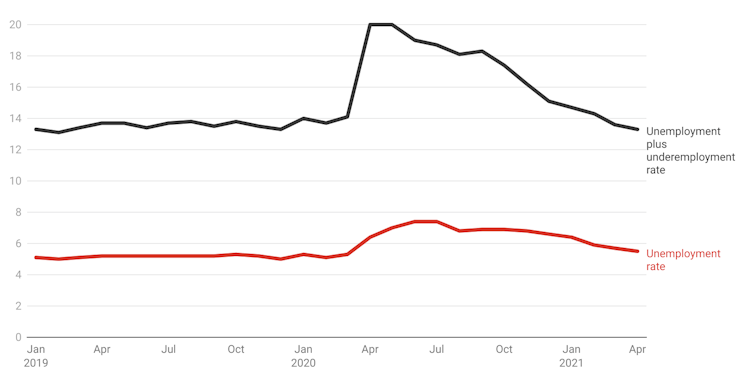

Unemployment and underemployment have affected about one Australian worker in eight (12-13%) for more a decade. Only expansive monetary, fiscal and wages policy offer any hope of boosting employment.

Unemployment and underemployment in Australia

Most immediately, the decision will benefit up to 200,000 workers paid the national minimum wage rate (which will increase to $20.33 an hour) and about 2.2 million employees that rely on awards whose conditions reflect the minimum conditions (that is, they aren’t covered by an enterprise agreement or other contract that guarantees them more).

The commission has ruled the increases won’t apply to most retail workers before September, and for those in aviation, tourism, fitness and a few retail sectors before November.

With these exceptions, the flow-on will be immediate for workers employed by reputable employers subject to union scrutiny. It may be slower in more informal enterprises where award compliance is more variable.

Read more: Resistance to raising the minimum wage reflects obsolete economic thinking

Indirect impacts

There will be flow-on affects to other workers, though less than in the past.

Up to the early 1990s, movements in one part of the award system rippled through to other job classifications in a very direct way. This has not been the case since workers – especially those on middle and upper incomes – have been required to bargain at enterprise level for wages.

Such “bargaining”, however, has been supressed for more than a decade, due to:

chronic and significant unemployment and underemployment

the crippling of union bargaining capacity through restraints on collective industrial action entrenched in the Fair Work Act

the imposition of legislated caps on wage increases for public-sector workers since the early 2010s, which have also helped suppress private-sector wages.

That said, having a publicly defined wages norm of 2.5% is helpful to all workers. It provides a benchmark for what is reasonable to claim in enterprise bargaining or negotiating an individual contract.

A hint of prices and wages accord

The Fair Work Commission tacitly noted it could have granted more.

Its decision, it said, was influenced by legislated changes to income tax that have benefited low and middle income earners. It also acknowledged the importance of the Superannuation Guarantee Levy increasing by 0.5% from July.

In weighing these factors there are elements of a tacit incomes policy – something Australia hasn’t had since the Hawke-Keating era of the 1980s and early 1990s.

During that period the federal government made agreements (known as prices and incomes accords) with the trade union movement to explicitly coordinate “industrial wages” (that is, actually wages) and the “social wage” (that is, provisions such as Medicare and superannuation that effectively increased living standards). In exchange for increases in the social wage, unions curbed their demands for industrial wage rise, which helped the government tackle inflation.

There are echoes of those ideas in this decision. Indeed Fair Work Commission president Ian Ross, who was in charge of the wage review, was a key official at the Australian Council of Trade Unions in the last years of the accords.

Getting the balance right

Institutions like the Fair Work Commission and its annual wages review are rare globally. It is the legacy of Australia’s pioneering system of regulated wages and employment conditions that began in 1904 with the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration. The court’s first landmark decision in 1907 (known as the Harvester decision) was to define and set a “living wage”.

Read more: A national living wage is on the table. Now let's talk about a global living wage

Over the decades this arbitration system has adjusted wages in light of changes to economic and social conditions. More often than not it has got the balance right – ensuring improved labour standards for workers in economically sustainable ways.

Even with the push for “labour market flexibility” since the 1980s, things – especially at the bottom of labour market – would certainly be worse were it not for the award system and its current custodian, the Fair Work Commission.

This decision reveals the commission can still provide important leadership in supporting recovery from a deep economic crisis. More will be needed if we are to “build back better”.

John Buchanan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.