During the 2022 federal election campaign, the Morrison government was all too eager to brandish its national security credentials. Its message to voters was that the Asia Pacific was brimming with threats from aggressive, authoritarian China.

Then, when Solomon Islands signed a secret security deal with China, Australian media attention swung sharply to the Pacific and commentators with little real experience of the region sprang into action.

The debate seemed to treat the Pacific as a vacant expanse where China was locked in a contest with the West, led by Australia as its chief representative. There was little discussion about the people of the Pacific themselves, their concerns about climate change and environmental degradation, or their development aspirations.

Since coming into office, the Albanese government has engaged the region with energy and a more positive tone. But as Australians we still need to do more to elevate the quality of public discussion about the region. Like others whose work focuses on the Pacific, I find it disappointing that media interest evaporates if there is no obvious “China angle”.

As the Pacific Islands Forum is holding its annual summit this week, we’ve asked experts on the Pacific to examine the great power competition in the region. How are countries like the US, Australia, China and others attempting to wield power and influence in the Pacific? And how effective has it been? You can read the rest of the series here.

To be sure, China’s behaviour in the Pacific is a legitimate matter of concern for both Australia and the region.

Beijing is investing heavily in its defence relations with the Pacific and promoting a different model of governance based on an authoritarian set of values. Many islanders are also concerned about creeping Chinese influence on the governance, media freedom and political independence of their nations.

The trouble is the way Australians talk about the Pacific often conveys the impression that “strategic denial” is the only motivation underpinning the country’s approach to the region – that we are more interested in excluding others than we are in the region itself.

There is nothing new about this. We are simply continuing a pattern that can be traced back to the very beginnings of colonial Australia.

Preventing settlement on the continent

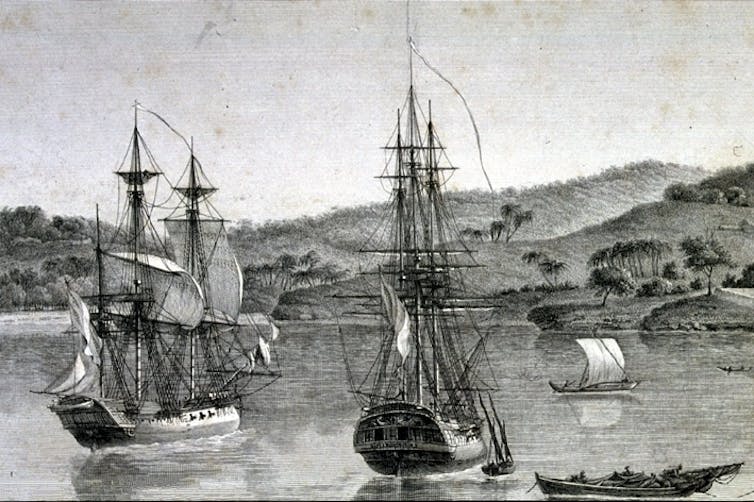

Denying the Pacific to others was among the reasons behind Britain’s decision to establish the New South Wales colony. The planners argued it would provide a base from which to attack Spanish commerce in the ocean. They also saw an opportunity to deny French occupation of the continent.

As British Home Secretary Lord Sydney noted in 1786, a settlement at Botany Bay would

be a means of preventing the emigration of Our European Neighbours to that Quarter.

The appointment of Arthur Philip as the first governor of the colony effectively put him in charge of the entire eastern half of the continent, as well as a vast expanse of ocean radiating out from Cape York in the north to the southern tip of what is now Tasmania.

In the early 1800s, the Australian colonies responded with anxiety to a series of strategic threats – real or perceived – from foreign powers in the Pacific.

For example, just after war broke out between Britain and Napoleon Bonaparte’s France in 1803, Governor Philip King dispatched an expedition to settle Van Diemen’s Land out of concern it might be of strategic use to France.

Two decades later, rumours of French plans for a colony in Western Australia motivated Britain to establish its own there, too.

Russia followed closely behind France as a perceived threat in the Pacific. This intensified in the 1850s when Britain was part of an alliance that fought Russia in the Crimean War. The movement of a Russian naval squadron near Australian waters in 1854 prompted the reorganisation of imperial forces in the colonies and the construction of defensive batteries around Sydney Harbour.

Then, in the late 19th century, alarm bells rang about the French again. Colonial officials and newspapers strongly opposed the establishment of a French penal colony in New Caledonia and settlement in New Hebrides (now Vanuatu), not far from Australia’s shores.

A new threat emerges

Around the same time, the newly unified Germany came to be regarded in the colonies as the main threat to “natural” British dominance in the Pacific. This concern focused on the island of New Guinea as German missionary and trading activity expanded there from the early 1870s.

The authorities in London thought the Australians’ concerns were overblown and had no wish to provoke either Berlin or Paris at a delicate time in European affairs.

This tension, however, led to one of the more dramatic moments in colonial history. Fearing imminent German annexation of New Guinea, Queensland Premier Thomas McIlwraith sent a police magistrate to Port Moresby in 1883 to claim the island on behalf of the British empire.

British authorities, however, suspected the move was motivated by a desire to source “blackbirding” labour for Queensland’s sugarcane plantations and refused to approve the action, sparking colonial outrage.

Just a year later, the British ended up establishing a protectorate in southeastern New Guinea anyway, after Germany moved into the northeastern corner. But Australian anger about the British “betrayal” did not subside, helping drive the push for an independent policy towards the Pacific and eventually Australian nationhood.

A national mindset on the Pacific takes hold

In fact, the first major convention of the colonies to discuss federation in 1883 was prompted by an immediate need to oppose French and German colonisation in the Pacific.

Around the same time, renewed tensions between Russia and Britain in the Pacific led to an expansion of the colonies’ military forces and the establishment of an auxiliary Royal Navy squadron in Australian waters.

So, when the Constitution was drafted in 1901, the framers specifically gave the Commonwealth the power to make laws “with the islands of the Pacific”. This reflected the growing sense that British authorities were not taking the colonies’ security concerns about the Pacific seriously enough.

A new national way of thinking of the Pacific was beginning to take hold. Early Australian leaders saw the Pacific similarly to how it was depicted during the 2022 election campaign – a vast, empty region where alien powers threatened Australian security interests.

And just like today, arguments for greater national sovereignty in defence came up against the belief that Australia’s security could best be guaranteed through an alliance with a major power.

For example, the Australian public strongly approved of a visit by the US Navy in 1908, which demonstrated to a rising Japan that Australia had powerful friends. But some voices were also critical of relying too heavily on the United States. The Bulletin magazine opined that if Japan was to attack,

there may be one chance in ten that the United States will be our ally.

Shifting our perspective

Throughout the 20th century, more conflicts and geopolitical rivalries have only strengthened this mindset that Australia must retain hegemony over the Pacific to keep threats at bay.

The second world war in the Pacific was crucial to shaping Australia’s defence posture and the misgivings it continues to have about potential threats.

In recent years, this concern has shifted from Japan and Germany to China. As it has emerged as a regional power, Beijing has taken an aggressive approach to security issues in the Pacific and attempted to woo Pacific partners with concessional finance arrangements and opaque support for politicians.

On the plus side, Australia’s relations with the region have matured. Canberra respected the post-war drive for independence in the Pacific and has poured billions of dollars in aid money into the region to help the new nations develop.

Australian diplomacy has also become more responsive to the concerns of island nations, and has been in the spotlight again this week during Prime Minister Anthony Albanese visit to Cook Islands for the Pacific Islands Forum.

But our public discussions about the Pacific still contain echoes of the past. This contributes to a narrow, seemingly insecure, viewpoint on the region.

The Morrison government’s mishandling of its communication with Pacific countries about the AUKUS initiative shows how a singular focus on strategic denial can undermine our relations. Pacific nations were shocked by the idea that nuclear-powered submarines would be deployed in their region, particularly those that had experienced nuclear testing in the past.

Some leaders lashed out, like Fijian Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama:

If we can spend trillions on missiles drones, and nuclear submarines, we can fund climate action.

Our diplomacy on this issue has improved since.

Successive Australian governments stretching back to the early colonial administrators were not necessarily wrong in pointing to the potential security threats arising from the activities of others in the region.

But the real failing – then and now – has been to project only these concerns in the way we talk to, and about, the Pacific.

Ian Kemish AM is affiliated with the ANU National Security College, Griffith Asia Institute and University of Queensland. His strategic advisory business Forridel assists private and public sector organisations with stakeholder engagement across the Indo-Pacific region. He also chairs KTF, a foundation which partners with the Australian Government, PNG authorities and several private sector entities.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.