Sturgeons are one of the oldest groups of fishes. Sporting an armor of five rows of bony, modified scales called dermal scutes and a sharklike tail fin, this group of several-hundred-pound beasts has survived for approximately 160 million years. Because their physical appearance has changed very little over time, supported by a slow rate of evolution, sturgeon have been called living fossils.

Despite their survival through several geological time periods, many present-day sturgeon species are at threat of extinction, with 17 of 27 species listed as “critically endangered.”

Conservation practitioners such as the Virginia Commonwealth University monitoring team are working hard to support recovery of Atlantic sturgeon in the Chesapeake Bay area. But it’s not clear what baseline population level people should strive toward restoring. How do today’s sturgeon populations compare with those of the past?

We are a molecular anthropologist and a biodiversity scientist who focus on species that people rely on for subsistence. We study the evolution, population health and resilience of these species over time to better understand humans’ interaction with their environments and the sustainability of food systems.

For our recent sturgeon project, we joined forces with fisheries conservation biologist Matt Balazik, who conducts on-the-ground monitoring of Atlantic sturgeon, and Torben Rick, a specialist in North American coastal zooarchaeology. Together, we wanted to look into the past and see how much sturgeon populations have changed, focusing on the James River in Virginia. A more nuanced understanding of the past could help conservationists better plan for the future.

Sturgeon loomed large for millennia

In North America, sturgeon have played important subsistence and cultural roles in Native communities, which marked the seasons by the fishes’ behavioral patterns. Large summertime aggregations of lake sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens) in the Great Lakes area inspired one folk name for the August full moon – the sturgeon moon. Woodland Era pottery remnants at archaeological sites from as long as 2,000 years ago show that the fall and springtime runs of Atlantic sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus) upstream were celebrated with feasting.

Archaeological finds of sturgeon remains support that early colonial settlers in North America, notably those who established Jamestown in the Chesapeake Bay area in 1607, also prized these fish. When Captain John Smith was leading Jamestown, he wrote “there was more sturgeon here than could be devoured by dog or man.” The fish may have helped the survival of this fortress-colony that was both stricken with drought and fostering turbulent relationships with the Native inhabitants.

This abundance is in stark contrast to today, when sightings of migrating fish are sparse. Exploitation during the past 300 years was the key driver of Atlantic sturgeon decline. Demand for caviar drove the relentless fishing pressure throughout the 19th century. The Chesapeake was the second-most exploited sturgeon fishery on the Eastern Seaboard up until the early 20th century, when the fish became scarce.

At that point, local protection regulations were established, but only in 1998 was a moratorium on harvesting these fish declared. Meanwhile, abundance of Atlantic sturgeon remained very low, which can be explained in part by their lifespan. Short-lived fish such as herring and shad can recover population numbers much faster than Atlantic sturgeon, which live for up to 60 years and take a long time to reach reproductive age – up to around 12 years for males and as many as 28 years for females.

To help manage and restore an endangered species, conservation biologists tend to split the population into groups based on ranges. The Chesapeake Bay is one of five “distinct population segments” the U.S. Endangered Species Act listing in 2012 created for Atlantic sturgeon.

Since then, conservationists have pioneered genetic studies on Atlantic sturgeon, demonstrating through the power of DNA that natal river – where an individual fish is born – and season of spawning are both important for distinguishing subpopulations within each regional group. Scientists have also described genetic diversity in Atlantic sturgeon; more genetic variety suggests they have more capacity to adapt when facing new, potentially challenging conditions.

Sturgeon DNA, then and now

Archaeological remains are a direct source of data on genetic diversity in the past. We can analyze the genetic makeup of sturgeons that lived hundreds of years ago, before intense overfishing depleted their numbers. Then we can compare that baseline with today’s genetic diversity.

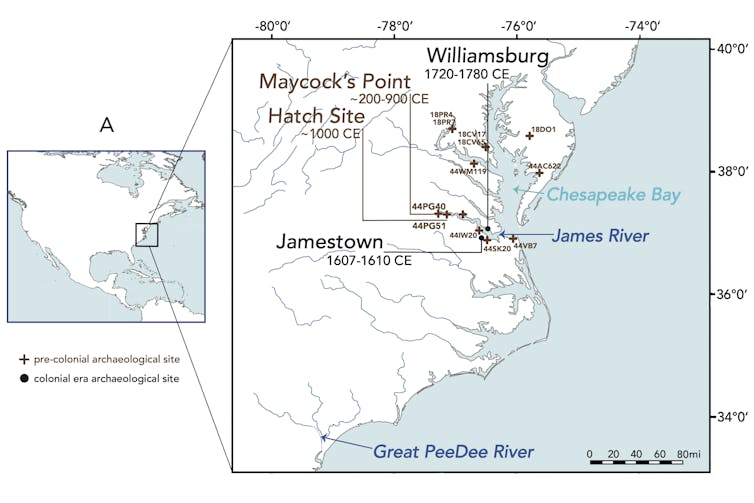

The James River was a great case study for testing out this approach, which we call an archaeogenomics time series. Having obtained information on the archaeology of the Chesapeake region from our collaborator Leslie Reeder-Myers, we sampled remains of sturgeon – their scutes and spines – at a precolonial-era site where people lived from about 200 C.E. to about 900 C.E. We also sampled from important colonial sites Jamestown (1607-1610) and Williamsburg (1720-1775). And we complemented that data from the past with tiny clips from the fins of present-day, live fish that Balazik and his team sampled during monitoring surveys.

DNA tends to get physically broken up and biochemically damaged with age. So we relied on special protocols in a lab dedicated to studying ancient DNA to minimize the risk of contamination and enhance our chances of successfully collecting genetic material from these sturgeon.

Atlantic sturgeon have 122 chromosomes of nuclear DNA – over five times as many as people do. We focused on a few genetic regions, just enough to get an idea of the James River population groupings and how genetically distinct they are from one another.

We were not surprised to see that fall-spawning and spring-spawning groups were genetically distinct. What stood out, though, was how starkly different they were, which is something that can happen when a population’s numbers drop to near-extinction levels.

We also looked at the fishes’ mitochondrial DNA, a compact molecule that is easier to obtain ancient DNA from compared with the nuclear chromosomes. With our collaborator Audrey Lin, we used the mitochondrial DNA to confirm our hypothesis that the fish from archaeological sites were more genetically diverse than present-day Atlantic sturgeon.

Strikingly, we discovered that mitochondrial DNA did not always group the fish by season or even by their natal river. This was unexpected, because Atlantic sturgeon tend to return to their natal rivers for breeding. Our interpretation of this genetic finding is that over very long timescales – many thousands of years – changes in the global climate and in local ecosystems would have driven a given sturgeon population to migrate into a new river system, and possibly at a later stage back to its original one. This notion is supported by other recent documentation of fish occasionally migrating over long distances and mixing with new groups.

Our study used archaeology, history and ecology together to describe the decline of Atlantic sturgeon. Based on the diminished genetic diversity we measured, we estimate that the Atlantic sturgeon populations we studied are about a fifth of what they were before colonial settlement. Less genetic variability means these smaller populations have less potential to adapt to changing conditions. Our findings will help conservationists plan into the future for the continued recovery of these living fossils.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.