Rising situates itself as a festival of new art, performance and music that takes place in the heart of Naarm/Melbourne just as the weather turns cold and the days get darker and shorter.

Now in its fourth year, the festival mapped out a walkable festival footprint in and around the CBD.

Rising has become known for unlocking and transforming hidden landmarks and spaces of the city. The festival provides access and a sometimes alternative perspective of the histories and memories of these sites.

Rising is engaging with ideas of the city as a site of power in determining how urban spaces and cityscapes are active mediums for defining categories of inclusion.

The festival is slowly working out what its voice is, and how it might want to impact this city. But significant actions and strategies still appear to be missing from its thinking and approach.

Interventions from First Nations artists

The city itself is a contested site of identity and belonging.

During lockdown in 2021, and returning again this year, The Rivers Sing heralded the end of each day.

From Deborah Cheetham Fraillon (Yorta Yorta), the extraordinarily haunting, large-scale audio installation echoed across the Yarra River with a vocal landscape of words from English and Boon Wurrung and Woiwurrung language.

The Blak Infinite, an art installation and exhibition curated by Kimberley Moulton (Yorta Yorta) and Kate ten Buuren (Taungurung), transformed Federation Square. The square became host to artworks exploring narratives of First People’s connection to the sovereign and political environmental movements.

The Blak Infinite was anchored by Embassy from Richard Bell (Kamilaroi, Kooma, Jiman and Gurang Gurang).

Embassy is a direct salute to the first Aboriginal Embassy that activists set up under a beach umbrella on the lawns of Parliament House in 1972. A tent that hosts public events and discussions, this installation has toured the world, creating a First-Nations-led urban space for reflection and action on Aboriginal rights.

The political and disruptive insertion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander narratives layered directly across and onto these sites creates a powerful tension. It reveals ongoing colonial impacts on city landscapes and actively demonstrates the exclusion of certain histories and cultural memories.

Making space for new audiences

This relationship with the city as a contested site of identity and belonging resonated with other work I saw during the festival.

In two performances, I experienced a strong sense of community gathering and coming together, which felt both political, disruptive and strategic.

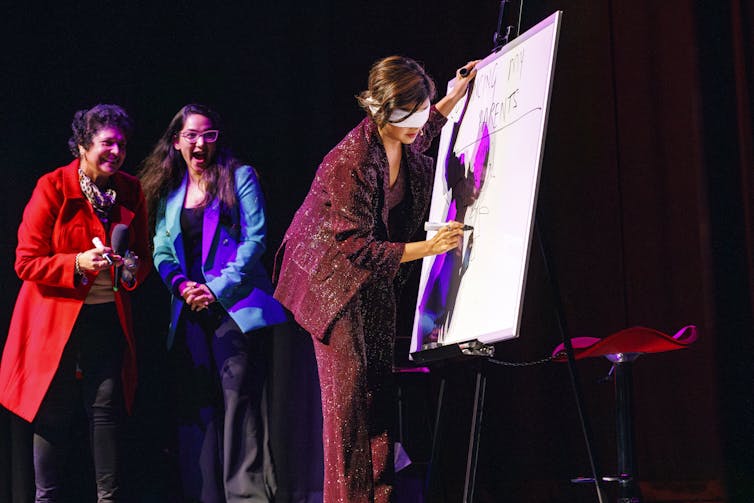

Toward the end of the festival, I was in the audience for Indian mentalist, magician, illusionist, YouTuber and consummate performer Suhani Shah in her first Australian show.

The show was full of intergenerational Indian families. The audience were thrilled and delighted by Shah’s set of impressive mind-reading tricks (which held little delight or interest for me, unfortunately).

The show felt largely out of place in an international arts festival. Perhaps it’s better suited to either a casino venue with its glitz and glam, or somewhere much more intimate.

Despite this, I was struck by the gathering of this particular community on a cold Wednesday night in the heart of the city. Whole families had arrived; there were young children dressed up in puffer jackets and shiny shoes and senior family members with limited mobility escorted by their adult children.

Rising says its ambition is to aspire to be a cultural leader in inclusion and access and for the festival program to be a true reflection of the city, representing people with a variety of life experiences, cultures and backgrounds.

In the presentation of Shah, something interesting is happening with this programming strategy. Shah drew a new and different audience base to the city and to a work in an often highly exclusive arts festival context.

Likewise, I spent a delighted three-and-a-half hours witnessing the incomparable theatre production of Counting and Cracking. This much-lauded show by S. Shakthidharan and Eamon Flack follows the epic and compelling journey of a Sri Lankan-Australian family over four generations from 1956 to 2004.

First staged in Sydney in 2019 and appearing at various festivals since then – including the Edinburgh International Arts Festival in 2022 – Counting and Cracking is bringing a new kind of Australian story to local and global audiences.

It is difficult to overestimate what it means for Australia to be reflected on stage in the way Counting and Cracking manages. Not only does it support the re-imagining of Australian identity as multicultural, intersectional and complex, it reveals in exciting ways our world-class capacity for original storytelling through performance.

Again, I was acutely aware of being in a largely non-white and heavily Sri Lankan audience.

The care and regard taken to welcome this gathering of people – including the provision of Sri Lankan street food available for purchase before, during and after the show – was a welcome reminder that the hosting of the audience is important.

It was necessary to ensure this story, which would resonate with many audience members in complex and often difficult ways, was held with care.

An uncertain future

The future of Rising remains under a question mark, with state government funding for future festivals yet to be confirmed.

As a festival of new performance, music and art, Rising’s strength lies in creative assembly and assembling on city sites as a political and disruptive action. These collective assemblies support the imagining of new stories, futures, communities and possibilities for both the city itself and the people who make up the communities within and around it.

The work in front of Rising is to strive to be both local and global, bringing the best out of Naarm and bringing the best to the city.

The question of who the festival is speaking to, with, for and how is key to its success – and remains unresolved.

Rising has great potential to continue to connect, shape and transform the existing arts ecosystem in the city. But this requires some deep consultation and consideration as it contemplates what the future holds.

Sarah Austin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.