This year’s OzAsia festival took place from October 19 to November 5, at its annual festival venues on the Kaurna land of Adelaide.

In its early years, the Asia-focused festival, which started in 2007, often highlighted work from a different Asian country each year.

Under the leadership of previous artistic director Joseph Mitchell, it became an event showcasing the best contemporary art from across Asia.

Now in her third and final year after the cancellation of the 2020 festival and smaller-scale festivals in the past two years, artistic director Annette Shun Wah has overseen the festival in full swing with invited artists from 13 countries.

As I attended this year’s festival, I had a chance to reflect on how Australia’s appreciation of multiculturalism and diversity is most evident in food.

Asians as others in Australian history

Despite its physical location in the Asia Pacific, Asians are minorities in Australia. One in eight of us were born in Asia, and one in six identify as Asian.

The first notable migration from Asia occurred in the mid-19th century during the gold rush, when Chinese miners came to Australia. By 1861, 3.3% of the Australian population was born in China – the highest percentage until the 1980s.

Working as a team, Chinese workers were more productive than Anglo and European miners, which led to conflict and anti-Chinese sentiments.

There was little social foundation for Australians to enjoy or appreciate artistic performances from Asia in and around the 1870s when performing arts companies from Japan came to Australia with acrobatic and juggling performances.

This was part of an international trend around the appreciation of Japanese culture known as Japonisme. How the Japanese performances were perceived and appreciated in Australia remains a mystery, as there was little review about these shows.

However, considering the monocultural nature of the colonial mindset, they probably did not contribute to Australia’s multiculturalism or diversity. Instead, they were likely seen as foreign performers delivering ethnic-based aesthetics.

Food as a vehicle to experience other cultures

Although observing performances is an obvious way to experience and learn about other cultures, food has acted as the medium through which a larger number of Australians learn about others.

Food has been an entry point to Asia for many Australians. Many words drawn from Asian cuisine – such as masala, tom yum and wasabi – are no longer foreign in Australian English.

Given this history, it makes sense that a hawker-style food market – introduced alongside the 2015 festival – came to be the Lucky Dumpling Market in 2017.

The night market style stalls along the River Torrens now attract a wide range of people to enjoy Asian food, before or after for a night out, or just coming to eat.

At the OzAsia festival’s A Night with Poh Ling Yeow and Sarah Tiong, I listened to Ling Yeow emphasise the diversity of food in Australia. She spoke of how Australians’ love for travel was a major factor leading to Australia’s multicultural food landscape.

Similarly, Tiong observed how Asian chefs are respected in the Australian food industry as they can bring diversity into the kitchen.

The Lucky Dumpling Market was packed during the weekend with food lovers, who enjoyed a variety of dumplings beyond the Chinese styles that have become orthodox in Australia, notably Japanese gyoza and Nepali momo.

In this year’s festival, I also observed two solo performances related to food, Jacob Rajan’s Paradise or the Impermanence of Ice Cream, and Yumi Umiumare’s Buried TeaBowl — OKUNI.

Ice cream and tea in solo performances

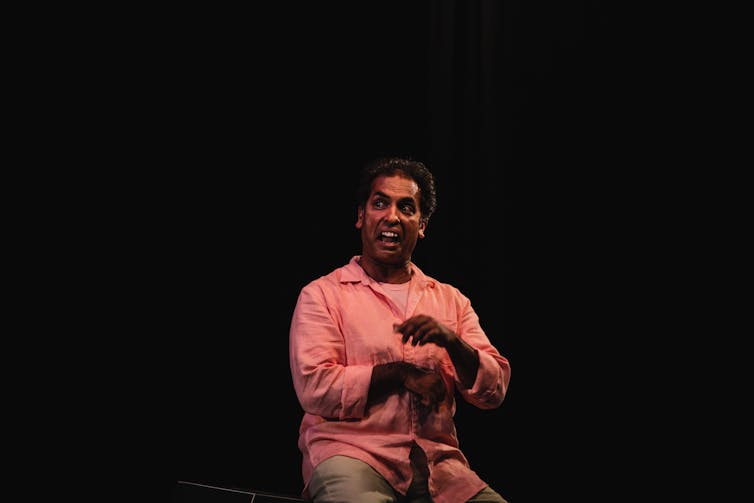

Rajan’s Paradise or the Impermanence of Ice Cream is a poetic and metaphysical reflection on the border between life and death. Rajan features as all seven characters, including an ice cream parlour server and chai seller.

The New Zealand actor’s capacity to show us diverse characters is exceptional and inventive. Jumping from Indian to Antipodean accents and back, he is a talented actor able to connect to Asia and Australasia.

With illustrations of life, migration and death, the world he conjures is recognisable to many Asian-Australians. Humour – including joking about Harvey Norman, possibly inserted for the Australian audience – is warmly received by the South Australian audience.

Set in India, Rajan shows us human sentiments are not limited by cultural boundaries.

In Buried TeaBowl — OKUNI, Yumi Umiumare, a Melbourne-based artist born and trained in Japan, combines a traditional tea making ceremony and contemporary dance, around a framework referencing the origins of Japan’s noh theatre.

The show highlights Umiumare’s complex relationship with her heritage and culture. She shows the audience how peace can be found through a cup of tea, and how this precious moment can be destroyed by drinking premixed tea from a plastic bottle.

Unlike Rajan, who performs in English, Umiumare uses her native language without subtitles from time to time. The majority of the show is performed in English, but the unsubtitled Japanese reflects a complex journey of herself as a performer and a migrant.

Without understanding every single word, the audience can still appreciate her overall performance, a mixture of traditional sentiments and contemporary dynamic expressions.

Understanding artistic performances requires more skills and knowledge than appreciating tasty food. Down by the river, many locals are enjoying Asian food – but do as many enjoy Asian art? There is a task ahead of us to extend appreciation of Asian culture beyond food and beyond the festival period.

Read more: Why aren't there more Asian faces on Australian screens?

Tets Kimura does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.