On a hot Wednesday morning in July 1990, Alanis Obomsawin was listening to the car radio on her way to work when she heard about shots fired in Kanehsatà:ke. Instead of continuing on to her office at the National Film Board of Canada in Montreal, she sped straight to the Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) community, about an hour’s drive outside the city. Obomsawin, who is Abenaki, would later tell a reporter that she knew an Indigenous person had to be there to document what was happening.

For months, the Kanehsata’kehró:non (Mohawks of Kanehsatà:ke) and a group called the Mohawk Warrior Society (later joined by surrounding communities) had been protesting the neighbouring town of Oka’s proposed golf course expansion and condo development. The planned building site would encroach on sacred Kanehsata’kehró:non land and a burial ground in an area known as the Pines. That spring, the Kanehsata’kehró:non land defenders sawed down trees to build a barricade along a dirt road and blocked access to the site. Tensions rose until, in early July, the Quebec government gave the protesters an ultimatum: take down the barricade or we’ll take it down for you. The Kanien’kehá:ka held their ground.

Before dawn on July 11, the Sûreté du Québec, the provincial police force, launched a raid, using tear gas, bullets, concussion grenades, and a front loader to try to tear down the barricade and break up the protest. The warriors fired back from within the Pines, forcing the SQ to retreat. Amid the chaos, an officer was shot and killed. (Though both sides blamed each other afterward, the identity of the shooter was never determined.) That morning marked the start of the Kanehsatà:ke Resistance, or what is commonly known as the Oka Crisis.

At nearly sixty, with fifteen film projects already under her belt, Obomsawin had by then established herself as a prominent director. A well-known Indigenous rights advocate, she had entered the world of documentaries through her activism. She was working on another film at the time, but as she drove to Kanehsatà:ke, her next documentary was in fact unfolding in front of her.

When Obomsawin first got to Kanehsatà:ke, she couldn’t get past the police, who were blocking the road to the community. She rushed back to Montreal to gather her equipment and crew. The next day, she returned to Kanehsatà:ke with a cameraperson and a friend. But it would be several days before she secured a pass and finally made it across the barricade and into the Pines.

Obomsawin didn’t know yet how long she’d be there. Didn’t know that, over the following weeks, the RCMP would be called in or that, at the province’s request, the Canadian Armed Forces would send in more than 2,500 soldiers. It was the largest number of troops deployed in Indigenous–settler conflicts to date, according to Audra Simpson, a professor of anthropology at Columbia University and the author of Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States. The army lined the woods with razor wire, effectively laying the warriors, land defenders, and the journalists embedded with them under siege. (The warriors at Kanehsatà:ke were mostly men, and the Mohawk Warrior Society is known in Kanien’kéha as the Rotisken’rakéhte, which can mean “carrying the burden of peace” or “carrying the bones.”) The standoff between the Kanien’kehá:ka and the army, the RCMP, and the provincial police lasted seventy-eight days, and Obomsawin would stay until the end.

She and her crew filmed clashes with the military; the army stopping food from reaching the land defenders; some locals hanging and burning an effigy of a warrior; a mob of Châteauguay residents stoning cars belonging to Kanien’kehá:ka, containing mostly women and children, with rocks the size of fists, windows shattering, glass shards lodged in skin, an elderly man hit in the chest, shirtless men cheering. She interviewed the Kanien’kehá:ka women on the front lines of the standoff with the federal and provincial governments. She documented the protests held in solidarity with the Kanehsata’kehró:non. And she filmed the army’s tanks pushing into Kanien’kehá:ka territory.

“If I said that I wasn’t afraid, I’d be lying,” Obomsawin tells me. “It was a war zone.” She recalls sleepless nights, running through the dark woods, the army’s sudden flares casting shadows along the eastern white pines. “It was very dangerous. For me, in particular.” The soldiers would call out to her from across the razor wire. “Every time I came to the front, they’d say, ‘Hey, here’s the squaw,’” she says. “And ‘squaw’ is a very beautiful word to describe a woman. But white people interpret that as ‘Here’s a woman I can fuck and beat.’”

When telephone contact was possible, Obomsawin’s superiors at the NFB pleaded with her to cross to safety. She refused, even after her crew left her alone behind the barricade. “There’s gonna be a massacre here, I’m getting out,” one cameraperson told her before he fled. The footage from the days afterward is shaky as she adjusted to using the equipment on her own. Some of the land defenders gradually left. By early September, few journalists remained; the CBC had pulled its reporters from the scene, citing fears of further violence. Some believe Obomsawin’s continued presence with a camera likely tempered the army—that things would have been worse if she weren’t there filming.

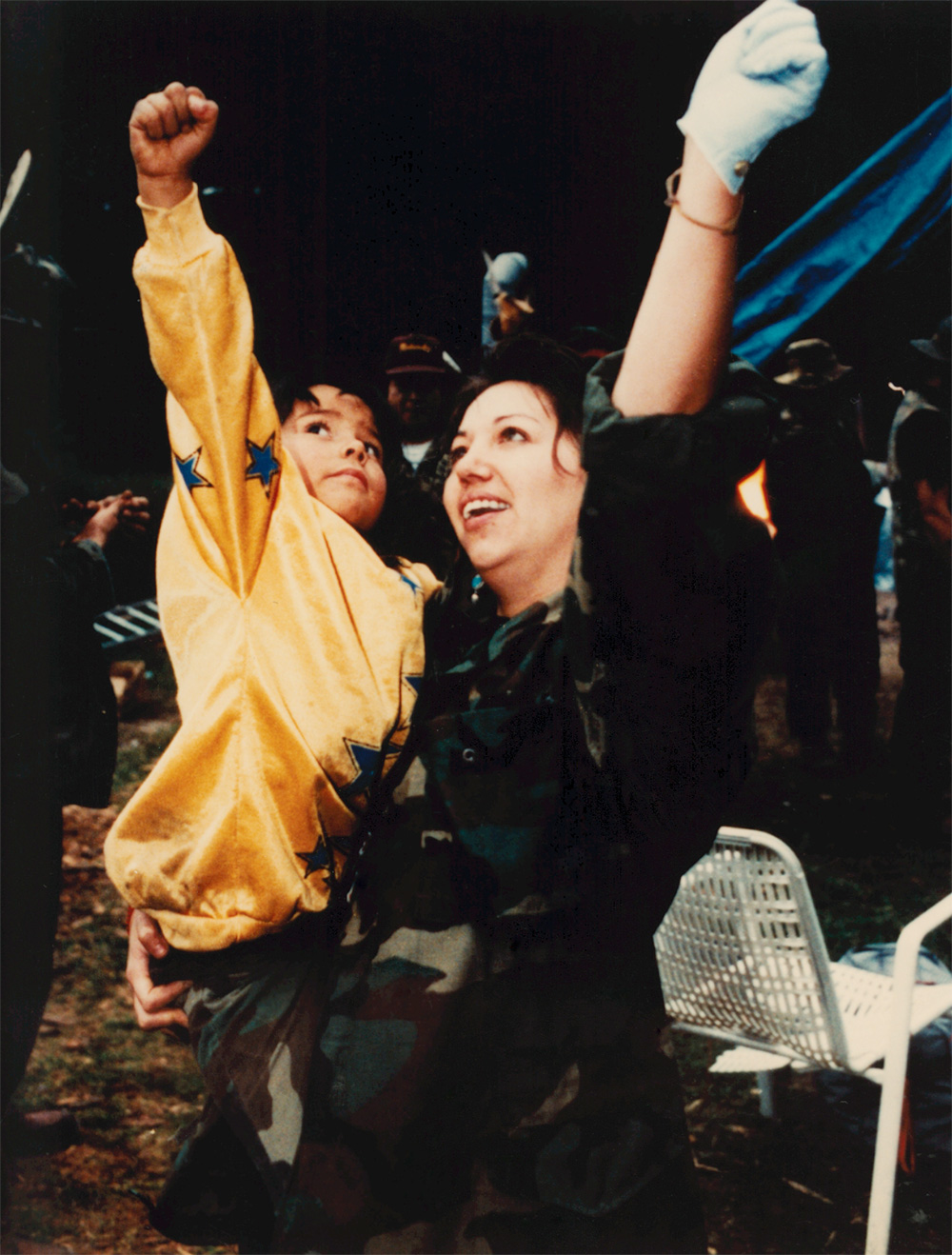

As the fall chill began to set in, the warriors told Obomsawin that they were planning to exit the barricade. She left the day before them, wanting to get her film reels safely past the soldiers. She’d seen the army confiscate tape from reporters, and she was determined this wouldn’t happen to her. Her crew was waiting for her on the other side of the line to film what was about to come. On September 26, the remaining land defenders—thirty warriors, sixteen women, and six children—built a fire, burned their weapons, walked toward the razor wire, and broke through. The soldiers, caught by surprise, tackled many of those leaving, handcuffing some and forcing their heads into the side of the road. They detained several Kanien’kehá:ka, two of whom were later convicted of aggravated assault and arms possession. Obomsawin and her crew were ready with their cameras, filming it all.

Three years later, after working through over 250 hours of 16 mm film—the most ever shot for an NFB production at the time, according to a 2006 biography of Obomsawin—she released Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance, the first of her four documentaries about Kanehsatà:ke. The film marked a watershed moment in the history of Indigenous cinema, says Jesse Wente, founding director of the Indigenous Screen Office and chair of the board of the Canada Council for the Arts. It was the first time, writes Randolph Lewis in Alanis Obomsawin: The Vision of a Native Filmmaker, that an Indigenous person had been in a position to create a well-funded account of state violence against Indigenous peoples and the resistance it was met with. Like so much of Obomsawin’s work, Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance gave voice to those often seen as secondary characters in Canada’s portrayal of itself. It also forced this country to confront the truth. Without Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance, “it’s hard to imagine the understanding Canadians would have of what happened there,” Wente says. In most other coverage at the time, “we did not hear from the people behind the line.”

Local news stories and CBC reporting about the Kanehsatà:ke Resistance, like so much coverage of Indigenous resistance in Canada, were often short on context and relied on government- and military-issued press releases. Even the name “Oka Crisis” is misleading, as if the conflict were focused on the predominantly white town of Oka rather than on Kanehsatà:ke or Kanien’kehá:ka land more generally. Some people call it “the Kanehsatà:ke Resistance,” “the Siege of Kanehsatà:ke,” “90,” or even “The War.” And as Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance makes clear, the siege wasn’t a stand-alone event; it was the latest fight in over 270 years of land dispossession. In many ways, it set the stage for the Indigenous land-back movements that followed.

Amidst the accolades and awards, some criticized the film for being “one sided.” For so long, documentary filmmakers, like journalists, were expected to be objective, to maintain distance from the people whose stories they told, to embody the “voice of god” narration style that runs throughout early NFB documentaries. “I can’t hide the fact that I have a point of view,” Obomsawin said in a CBC interview after the film was released. “Every film I’ve made, there’s a point of view.”

In the early afternoon on a cool Tuesday last December, Obomsawin brews a pot of tea in her office on the third floor of the NFB building in downtown Montreal. The walls are lined with posters of some of her movies: Trick or Treaty?, We Can’t Make the Same Mistake Twice, Our People Will Be Healed. A large dream catcher, white feathers dangling, hangs in the window overlooking the city; it’s a gift from Esgenoôpetitj, a community she filmed in decades ago. Obomsawin has made nearly a film a year since her first movie was released in 1971. Now, at ninety-one, she’s completed fifty-six films, and is working on her next two.

Obomsawin’s an early riser and is typically one of the first to arrive at the building. She’s wearing heels, as she often does. Her black hair is pulled back, and a silver horse brooch is pinned to her blouse. Beside her desk is a stack of books that accompanied a retrospective in Berlin last year. “It was like seventy years of my work,” she says after handing me a mug of tea, blue cornflower petals floating in the steaming water. “So you can imagine the space it was taking, many different rooms.”

The exhibit, which opens at the Art Museum at the University of Toronto in September, traces her years as an Indigenous rights activist, a singer, and a filmmaker. Obomsawin performed in New York City in the 1960s and at the Mariposa Folk Festival, which she helped organize. She also played at Woodstock, where Ramblin’ Jack Elliott is rumoured to have written a song about her knees. She was friends with Leonard Cohen and hung out with artists who frequented bohemian Montreal spots like the Swiss Hut and the Bistro. She sang in Abenaki, French, and English. “With her glistening eyes and jet-black braids,” Lewis writes in Alanis Obomsawin, quoting a journalist, “Obomsawin cut a striking figure around town, singing and telling stories at parties and coffee houses.” But Obomsawin is now best known for her films.

“I think it’s probably safe to say that she’s the most important filmmaker in the history of Canada,” Wente says. “It’s hard to imagine someone else who has had quite the same influence on Canada’s understanding of itself as Alanis.” She created a road map, a road even, for other Indigenous filmmakers to follow. Indigenous cinema itself, says Wente, can be traced back to Obomsawin and the late Māori filmmaker Merata Mita. “Alanis was out there, paving the way for my generation,” Tracey Deer, a Kanien’kehá:ka director, tells me from her office in Kahnawà:ke. “She’s like the grandmother of all of us.”

Obomsawin has by now won most of the major awards in her field. A few years ago, at a ceremony for her Glenn Gould Prize, she showed up in a voluminous full-length red satin jacket. (She often wears red to honour missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.) “She’s not just iconic to the Indigenous film community,” says Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers, Blackfoot and Sámi director and actor. “She’s iconic to Indigenous people as a whole.”

Obomsawin’s stamina is part of her legend. “I remember being at this gay bar in Berlin at, like, 4 a.m., with pink fuzzy walls, and there was Alanis,” says Tailfeathers, recalling a night during the Berlin International Film Festival about a decade ago. “She’s at the festivals, and she comes to the screenings, and she comes to the gatherings.” Sometimes, when Obomsawin is participating in a Q&A, she’ll say to the audience, “Let’s dance,” and there’s a sense that she just might.

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, when Obomsawin was working from home, she went through her archives, listening to old recordings. She’d felt an urgency to create documentaries from her old audio and footage. She spread the recordings across her long dining table in the greystone house in Montreal where she’s lived for over fifty years. Since then, she’s been juggling four or five films at a time. “For Alanis, her work is her life,” Alison Burns, Obomsawin’s editor and close collaborator for the past twenty-plus years, tells me in an email. “You’d think that someone working into her late 80s and now 90s would be slowing down,” says Burns. “Alanis seems to be speeding up.”

Obomsawin was born during a solar eclipse in the summer of 1932. From the bed where she laboured, her mother could see out a window: neighbours stood on roofs, craning their necks, to watch the afternoon sky. When the moon’s shadow moved across the sun, complete darkness fell, and Obomsawin was born.

She grew up at a time when the government forcibly took children from their families and sent them to church-run residential schools. Except for some First Nations men who were enfranchised, Indigenous people didn’t have the right to vote in Canadian elections. First Nations women who married non-status men lost their status. Religious ceremonies and cultural gatherings were illegal: singing, dancing, and wearing regalia could, and did, land First Nations people in jail.

Obomsawin did not attend residential school. She lived her early years in Odanak, an Abenaki reserve about an hour’s drive northeast of Montreal. There was a dirt road and a well, no electricity or running water. These are years she speaks fondly about: the smell of the bread her aunt baked, the sweetgrass Obomsawin braided. Most women in Odanak were basket makers, and Obomsawin loved to watch the ash splints hanging on the lines after they’d been dyed bright colours—deep purple, lemon yellow—curling and moving in the wind as they dried. She recalls the moose, bears, beavers, and muskrats, and how she used to squeeze into her family’s chicken coop and imitate the hens. Some men in Odanak, including her father, were seasonal hunting and fishing guides, and some made birch-bark canoes.

The evenings were lit by oil lamps, and Obomsawin and the other children listened to the adults tell stories in Abenaki—the language Obomsawin grew up speaking—about their lives, their history, the animal world. “So if a person, an adult, told a story, you had no images; it was your imagination. And if you had four or five children there, you had four or five films right there, because we’re all imagining it differently,” she says. The stories her father told about bears were her favourite.

Obomsawin has become the raison d’être of Canada’s public film producer and distributor.

In 1941, when Alanis (pronounced Ah-la-nees) was nine, she moved with her parents to Trois-Rivières, a town on the Saint Lawrence River, about a forty-five-minute drive north of Odanak. The air stank because of a pulp and paper mill. “My life there was very bad as a child, mainly because of the history book they were teaching us,” she says, recalling the school she attended. “We were savages, and our language was Satan’s language, and . . . we didn’t have any religion. All that was written in the book. That’s what the children were hearing.” Obomsawin was the only Indigenous child in her school, and the other children often beat her up and called her sauvagesse (savage).

These are the years that drive Obomsawin’s life’s work—her advocacy for the well-being of Indigenous children, her films about Indigenous rights, correcting and rewriting the history that she was taught in school. These are also years she doesn’t like to talk about much. “You see it very well in When All the Leaves Are Gone,” she says. “That’s really my story.”

The 2010 film is a seventeen-minute work of autofiction about Wato, Obomsawin’s proxy, the only Indigenous student in an all-white 1940s school. Eight-year-old Wato is shy, her black hair cut into a chin-length bob. She misses the loving reserve she called home. One day, Wato’s teacher, a nun, reads from a history book: “The savages were ignorant and pagans.” Wato becomes the target of her classmates’ bullying and abuse. She finds solace and strength when she dreams. Two horses appear on a grassy knoll overlooking a stream, and they dance with her.

Obomsawin has a trove of stories she tells to explain the path of her life. She recounts them skillfully, with the same lilting cadence that narrates most of her films, embodying characters and impersonating voices, recalling stirring details. But when she speaks of her time in Trois-Rivières—of the loneliness she felt there, the hatred she experienced, and of her father passing away—she holds her hands in her lap and pauses. “It makes me very sad to talk about that,” she tells me. Her father, Herman Robert Obomsawin, died of tuberculosis in 1944 when Obomsawin was twelve. “I was sure I was going to see him again.” She thought she’d meet him in the street. She wrote him letters. “You know the imagination of a child, I guess.”

One story she often tells is how, after her father passed away, she decided she wasn’t going to get beat up anymore. Outside, during recess, she kept her back to the brick wall so no one could sneak up behind her. And if anyone called her a savage, she beat them up. “I was just surviving everything,” she recalls. “Fighting back.”

The Saint-François River runs along the edge of Odanak. It was polluted when Obomsawin swam in it as a kid, and over the years, it became dirtier and dirtier until, in the 1960s, it was declared no longer safe to swim in. By then, Obomsawin was in her thirties and living between Montreal and Odanak, as she does today, and she was making a name for herself as an activist and a singer. She appeared frequently in news stories and on panels, talking about Indigenous rights, history, treaties, land. She sang in schools and prisons.

One day, when Obomsawin was in Odanak, she saw two children crying. They’d gone to the pool in the neighbouring town of Pierreville, since they could no longer swim in the river. They told her they had money to pay for the admission but they were turned away. “No savages here,” they were told. Obomsawin and the community decided they would build their own pool, in Odanak, and she set about fundraising the roughly $18,000 the project would cost.

In 1966, the CBC documentary series Telescope profiled Obomsawin in Alanis, a twenty-three-minute black-and-white film centred around the pool project. In a series of clips, she describes gathering donations, putting on fundraising concerts and other events, and getting the permits to start building. “Then there was a white man I had to deal with, they didn’t believe in the idea,” she says in the film. “They were saying things like this to me, you know, ‘A swimming pool for Indians, why—that’s luxury.’ This is the type of mind they had when I began.” They didn’t realize, she says, that “we were going to get that pool no matter what.” The pool is still there today and is open to all.

The Telescope segment, which aired nationally in a prime-time spot, caught the attention of some of the staff at the NFB, including Robert Verrall, a director and illustrator. The NFB reached out to Obomsawin, asking about her work. Obomsawin and Verrall met over dinner at a Chinese restaurant in downtown Montreal, and Verrall remembers that, at one point in the conversation, Obomsawin shared her views on the portrayal of Indigenous peoples in NFB films. “Something that she said hit me like a lightning bolt,” Verrall, who is now ninety-five, recalls. “She had seen NFB films about her people, but there was always, almost always, a narrator expressing the sentiments of white culture. But you never heard the people talk.” Eventually, Obomsawin was offered a job at the NFB. She began working there in 1967.

Those early years were tough. She was one of the few Indigenous people in a white male–dominated government institution. She didn’t have enough funding to make her own films at first. As a consultant, she accompanied non-Indigenous teams to film in Indigenous communities. “I realized they were just using me to get on the reserve,” she says. After one such project out west, she’d had enough. “I told them I’m never, never doing this again. Don’t ask me to take anybody anywhere. And I was very strict about that.”

She started working with a department within the NFB that created educational kits for schools across Canada. Verrall became a trusted colleague and friend, and he supported her work even after he retired in 1985. (Obomsawin called him while she was documenting the Kanehsatà:ke Resistance and later asked him to create illustrations for Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance.) Here was her chance to change what children were hearing in schools, to challenge racist narratives like the ones she was taught in the classroom. She collaborated with Indigenous communities to craft their stories. She created film strips accompanied by recordings in Indigenous languages. This work set her in the direction of non-fiction filmmaking.

Her first documentary, Christmas at Moose Factory (1971), was shot at a residential school in the Cree community of Moose Factory in Northern Ontario. The thirteen-minute film is narrated through children’s drawings and stories—about eating bannock and muskrat, seeing a bear, snowmobiling, and decorating a Christmas tree. It’s quietly radical, centring Indigenous children at a time when colonial forces routinely stripped them of their voices.

The film set the stage for Obomsawin’s revolutionary streak in documentary filmmaking. What distinguishes her work, says Wente, is what he describes as a “cinema of listening.” Usually, before the cameras start rolling, Obomsawin, who often films in First Nations communities, travels to each location with her Nagra recorder, meets with locals, and listens to them. “It’s not my film, it’s somebody else’s story,” she tells me. “I have to really listen, for a long time.”

These early recordings, which are essential to her process—her interviewees often speak more openly without cameras present—are overlaid with footage shot later. “For me, that’s very sacred, because it’s the voice of the people who feel relaxed,” she says. She encourages interviewees to let her know if, in hindsight, they find themselves uncomfortable with what they’ve said. “I tell them, ‘Tell me, and we’ll just erase it,’” she says. “And I would never cheat them.”

Obomsawin’s approach was instilled in her as she grew up in Odanak, during her time spent listening to stories. “The voice is like a song,” she says. “It changes if they talk about something sad or happy.” Speaking from an Anishinaabe perspective, Wente likens her listening approach to the importance of talking circles. “When you sit in circle, everyone gets a turn to talk, but the real power comes in waiting your turn and listening,” he says. “The whole point of the circle is that everyone gets to say what they want to say. Only after that’s done are you able to move in the right way.”

Until a few years ago, the NFB was headquartered in a sprawling suburban complex off a Montreal highway. In 2019, it moved into its new downtown space, a slick thirteen-storey building designed with Obomsawin in mind. In a reception room on the main floor, a recording of an interview with her plays on loop. On the second floor is the 138-seat Alanis Obomsawin Theatre. A few floors above, a still from Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance covers the wall of a conference room. If her work and image are part of the building’s DNA, it’s because she has become, as Wente puts it, the raison d’être of Canada’s public film producer and distributor. “If you were to ask me why the NFB should exist,” Wente tells me, “she’s why. She’s who I would point to.”

It’s a remarkable development, given the NFB’s origins. The film board got its start in 1939, with Scottish filmmaker John Grierson appointed as its commissioner. Grierson, who coined the term “documentary,” is often considered the father of Canadian and British documentary film. (Despite their differences, he later became a close friend of Obomsawin’s and the godfather of her adopted daughter.) As Canada entered World War II, the board focused its production on propaganda films, which Grierson oversaw and which largely presented an imagined homogenous Canadian nation, a white male Christian “we.”

During the NFB’s formative years, the government regularly commissioned it to make films promoting federal policies, including the Indian residential school system. Films like Northern Schooldays (1958) and No Longer Vanishing (1955) are glowing depictions of residential schools and the assimilation of Indigenous peoples. Travelling projectionists would drive from town to town, showing them in community centres, churches, schools, and residential schools. Of these years, film scholar Joel Hugues writes: “I view the relationship between the NFB and [the Indian residential school] system as one invested in the destruction and production of a culture.”

In other early English-language NFB films featuring Indigenous peoples, predictable tropes and problematic framings run throughout: cultures destined to disappear, people frozen in time. But calls for Indigenous rights and better representation were gaining traction in the US and Canada by the time Obomsawin joined the NFB, in 1967, amid the rise of the “red power” movement. In 1968, the NFB established the Indian Film Crew as part of an initiative to train Indigenous creators in filmmaking. Obomsawin wasn’t part of the crew, but internal NFB memos show how she advocated for the increased involvement of Indigenous creators, a goal she’s been committed to ever since—sitting on various boards and recruiting, supporting, and mentoring Indigenous filmmakers.

But she had to fight to get her early films made. Since the NFB had limited funds, it encouraged its filmmakers to approach government offices for money. She knocked on doors, going to government offices, including what was then called the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, which oversaw state- and church-run residential schools.

In her film Amisk (1977), Obomsawin brought together Indigenous musicians from across the country for the James Bay Festival, a show of support for the James Bay Cree, whose territory, resources, and culture were threatened by the expansion of hydroelectric dams. By the time performers started arriving in Montreal, some of the funds hadn’t come through. Some of the performers’ plane tickets were billed under Obomsawin’s name, and she could no longer give the artists their per diems or put them up in a hotel like she’d planned. She managed to find them rooms at the YMCA, and each night, she cooked supper for whoever showed up at her house. Friends left prepped meals in pots on her front steps. She took on speaking engagements to pay off the flight charges.

“She told me that I wasn’t allowed to interview any white people. And of course, I didn’t obey her.”

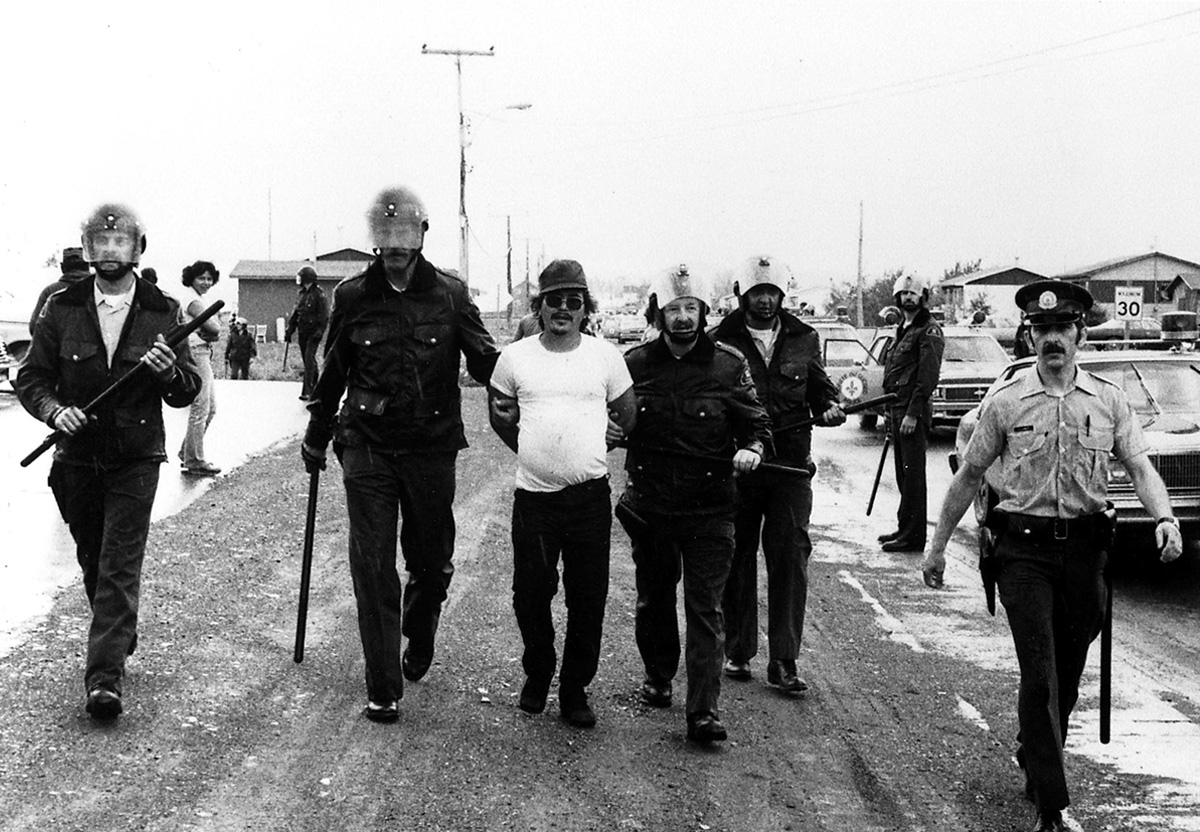

But one of her biggest, career-defining battles was yet to come. On June 11, 1981, helicopters circled over what was then known as the Restigouche (Listuguj) reserve, a Mi’kmaw community in Quebec on the northern shore of the Restigouche River. More than 500 members of the SQ stormed the community, dressed in riot gear. It was the first of two raids ordered by then premier René Lévesque to impose restrictions on the community’s salmon-fishing rights. SQ officers arrested and beat Mi’kmaq, destroyed and confiscated fishing equipment, and searched houses. Obomsawin wanted to go to Listuguj with a film crew as soon as the news broke, but the slow-moving approval process within the NFB made it impossible for her to get there quickly. When she finally got the go-ahead to start shooting, the head of the programming committee implied there would be repercussions if Obomsawin didn’t meet the board’s conditions.

“She told me that I wasn’t allowed to interview any white people. I could only interview Indians,” says Obomsawin. She doesn’t remember being given a reason for the directive but feels that it was rooted in racism. “It was very bad. And of course, I didn’t obey her.”

One of the film’s most arresting moments is a tense on-camera interview, conducted in her living room, with then Quebec minister of recreation, wildlife, and fisheries Lucien Lessard, who oversaw the raids. “When you came to Restigouche,” Obomsawin says in French, pointing at Lessard, “I was outraged by what you said to the Band Council. It was dreadful.”

Her voice rising, she recalls what Lessard said to the chief of Listuguj: “‘You cannot ask for sovereignty, because to have sovereignty, one must have one’s own culture, language, and land.’”

After some back and forth, Lessard, who smokes a cigarette during a part of the interview, says, “Do you mean to tell me at this point Montreal too belongs to you?”

“Of course,” says Obomsawin. “All of Canada belongs to us.”

When the head of programming learned about the interview, Obomsawin tells me, “she was so mad. And she really raised hell with me, and I raised hell with her. I said, ‘Who the hell do you think you are telling me who I can talk to or not?’”

Fighting within the board and funding issues further delayed the film. But when Incident at Restigouche was finally released, three years after the raids, it earned Obomsawin a new level of respect among her colleagues. Outside of the NFB, it further solidified Obomsawin’s place as a serious documentarian.

As Incident at Restigouche circulated at film festivals, it screened in Guelph in 1984 alongside Bastion Point: Day 507 (1980), a film by the late Māori filmmaker Merata Mita that documented the struggle for Māori land rights. Mita and Obomsawin both attended the festival.

What Obomsawin was doing in Canada, Mita was doing in New Zealand. Both women were activists before they were filmmakers, both were fighting to amplify Indigenous voices, both refused to let industry standards stifle them. And they became good friends. “She was like my sister,” Obomsawin says. Wente says their meeting was the moment “when Indigenous cinema became a global community.”

In the mid-1990s, Tracey Deer was far from home, a freshman studying film at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, when she watched Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance in one of her classes. She ran out of the classroom and cried in the hallway.

“All of my trauma came rushing back to me,” Deer, now forty-five, tells me on the phone from her office in Kahnawà:ke, where she’s from. “That was the first time I had revisited the Oka Crisis since I lived it as a twelve-year-old.” It was also the first time Deer had seen a film created by an Indigenous person. “This was an insider perspective; it was on our side of the line,” recalls Deer. “Up until then, what I’d been exposed to was from Hollywood. It was a lot of feathers,” she says. “But Alanis’s work changed that.”

Now a director, Deer’s feature film Beans (2020), which takes place during the Kanehsatà:ke Resistance, won the 2021 Canadian Screen Award for Best Picture. (Last year, Deer directed episodes of the Peacock series Rutherford Falls. The show had a multi-nation Indigenous writing team and was led by a Navajo showrunner.) The film sees the standoff through the eyes of twelve-year-old Tekahentahkhwa (one of Deer’s middle names). A number of historical recreations in Beans are pulled directly from events that Obomsawin captured—events that other media didn’t document, Deer says, having scoured news archives for years to research the Kanehsatà:ke Resistance.

“The Indigenous film community owes [Obomsawin] a great debt,” Tailfeathers says, speaking to me via Zoom from her mother’s home on the Kainai Nation’s Blood reserve. “So often, Indigenous voices on screen are represented in such monolithic ways. You’ll hear one or two people speak for a community.”

There can be a push when pitching a film, Tailfeathers says, to answer a standard list of questions: “‘Who are your key characters?’ and ‘How are we going to experience this film through their eyes?’” But Obomsawin’s documentaries, which often feature dozens of voices (Kanehsatake, for example, includes interviews with more than seventy people), defy that convention. A person might appear on screen for only a minute or two—an approach that reflects her listening practice.

When Tailfeathers was working on a documentary about the impacts of the overdose epidemic in her community, she felt overwhelmed by the responsibility of representing thousands of people through a handful of central voices. Obomsawin’s work had shown her what else was possible. “I’m really grateful that I could point to her films and be like, ‘Hey, look,’” says Tailfeathers. “‘If she can do it, why can’t I?’”

On a spring evening last year, the late Mi’kmaw filmmaker Jeff Barnaby joined Obomsawin on stage at the NFB’s Alanis Obomsawin Theatre. “She was the first one that taught me that you could take a film and you could turn it not only into this cultural touchstone but also have it be a voice of protest,” Barnaby told the audience.

Barnaby grew up in Listuguj. The salmon raids documented in Obomsawin’s Incident at Restigouche were among his first memories. His friends and family are in the film. “I think about it almost as a home video,” Barnaby said. When the documentary was released, he recalled, “it flooded the reserve. Everybody had a copy of it, and we’d watch it all the time.”

The last film Barnaby made before he died of cancer in 2022 was Blood Quantum (2019), which premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival and received the most nominations of any film at the 2021 Canadian Screen Awards. He asked actors to watch Incident at Restigouche as part of the audition process.

Blood Quantum, a zombie movie with sharp socio-political undertones, is set in 1981, on the Red Crow Reserve, a fictional Mi’kmaw community. In the film, the dead are coming back to life but the Indigenous inhabitants are immune to the zombie virus. The film opens with an apparent nod to the salmon raids: a gutted fish is the first to rise from the dead. The final scene echoes a moment in Incident at Restigouche. “[The police] were all over the roads, picking up nets,” an elderly man says in Mi’kmawi’simk in Obomsawin’s film. His thick greying eyebrows frame his gaze. Gesturing with his hands, recalling what he told the police marching into his community, he says, “I take my axe. I draw a line for them not to come any further.” Barnaby wrote this scene right into Blood Quantum.

“That film is forty years old,” said Barnaby, during what would be his last public-speaking engagement before he died. “And it inspired me to be who I am.”

“How aware are you of the legacy you’ve created?” I ask Obomsawin. Outside her office window, the morning sky is bright over downtown Montreal.

“I don’t think about that,” she replies quickly, as if the time spent contemplating what she’s built is less time for the work she’s doing now. A couple of years ago, in an onstage interview during a TIFF retrospective of her work, Obomsawin said she would make films until she can no longer physically do so, “then I will go and rock the babies in the hospital and sing them lullabies.” Until then, she’ll be making another film—and another film.

After I leave Obomsawin’s office, she heads back to the editing suite. She’s planning to drive northeast to Odanak later in the day. There’s a storm coming, and she wants to get on the road before the snow starts. But first, she needs to check on the rough cut of her next film. Her heels echo as she walks down the hall.