Thousands of Mexicans are fleeing their homes to seek asylum in the United States, fearing their children might be kidnapped by ultra-violent drug cartels to become hitmen or sex slaves.

Last year, nearly a third of migrants intercepted at the southern US border were Mexican -- around 740,000 -- more than from Venezuela, Guatemala or Honduras, according to the International Organization for Migration.

"All the people in my town fled for the same reason: the kidnapping of sons and daughters for money," said Juan, who did not want to give his real name.

The 37-year-old said that he was abducted by a criminal group called Los Tlacos in Mexico's violence-plagued southern state of Guerrero.

A cartel leader told Juan that "if I didn't work for him he would take my children," a 13-year-old boy and two girls aged 14 and 17.

The gangster was going to "train" the boy and wanted the girls "for himself," said Juan, who worked as a cook for the cartel.

He even filmed footage of murder victims for the gang to send to its rivals, he said, fighting back tears.

After a fortnight in captivity, Juan managed to escape and fled Mexico with his grandmother, wife and children.

Crime is one of the main challenges awaiting Mexico's next president as the country prepares to hold elections on June 2.

Despite a growing economy, political stability and reduced poverty, outgoing left-wing populist Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador has failed to stop a spiral of cartel-related violence.

Several years ago, shelters near the Mexican-US border were overwhelmed by a wave of migrants from Central and South America.

Today, around 70-85 percent of guests at the shelters are Mexican, managers of two centers told AFP.

Elena's eldest daughter is a teenager with black hair and a pretty face who caught the attention of a young gang member.

"He looked at her at a party said: 'she must be mine,'" the 39-year-old said.

So Elena fled with her mother and two daughters.

She saw no point in reporting the incident to the authorities in the town of Acapetlahuaya in Guerrero.

Local officials "are bought" by criminals and going to the police would be a death sentence, she said.

Instead Elena decided to return to the United States, where her daughters were born while she was living without documentation until she was deported in 2018.

"I want the government to give me asylum to be safe from crime," said Elena, whose name has been changed to protect her identity.

Kidnappings and homicides are daily occurrences in Mexico, where more than 450,000 people have been murdered since the government launched a military offensive against drug cartels in 2006.

In Iguala, a city in Guerrero, violence was an unavoidable part of life, 18-year-old Pedro said.

"Dead people were left in the street almost every day," said the apprentice construction worker.

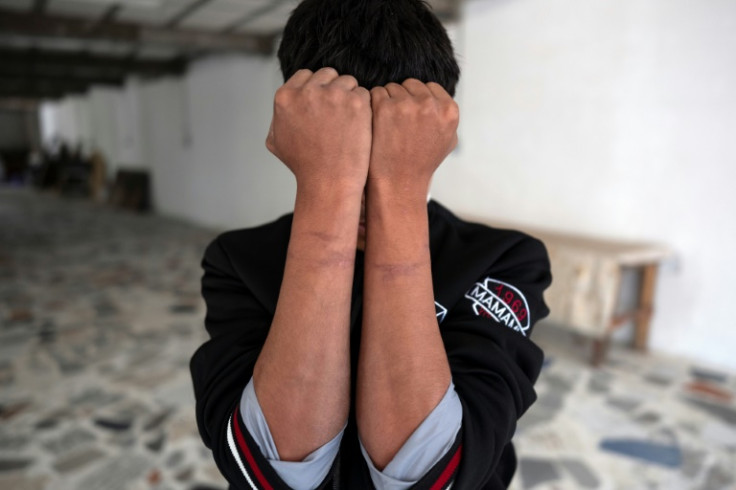

Pedro was walking with a friend when gunmen in pick-up trucks took them, he said.

He was struck on the head and feet and threatened with a machete before being forced to work in drug cultivation.

At night, "they tied us up so we wouldn't escape," he said, his wrists still sore.

After six months, Pedro managed to evade his captors and ran for almost four days through the mountains to Iguala.

Now in Tijuana, he is seeking asylum in the United States, where he has relatives.

"I want to leave this country because I'm afraid," he said.

Some 40 million people of Mexican origin live in the United States, following a century of migration that was mostly motivated by the need to earn a living.

Since 2022, criminal violence has prompted another wave to seek to join them, according to Jose Maria Garcia, manager of the Juventud 2000 shelter.

Most are hoping to get asylum in the United States, he said, adding: "Many of them don't have anything to return to."

Juan's first asylum request was rejected, but he has not given up.

"I hope they give it to me for my children. I want them to be in a better, safe place -- to not grow up struggling and suffering," he said.