You’re probably reading this article on a device assembled in Asia, using materials shipped there from all around the world. After it was made, your phone or laptop most likely travelled to your country on a huge ship powered by one of the world’s largest diesel engines, one of thousands plying the world’s oceans. All this maritime activity adds up: international shipping burns over 200 million tonnes of fossil fuels a year.

The sector is trying to clean up its act. Its 2023 global climate strategy set a “strive” ambition of 30% cuts in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, relative to 2008 emissions and 80% by 2040. That’s close to a level of ambition that can deliver on the Paris climate agreement, but this target urgently needs policies to make it happen. This is also urgent: 2030 is only five years away.

The technology to deliver a rapid transition exists. Wind propulsion technology – yes, sails – can be fitted to existing ships, and much of the sector could soon switch to zero-emission fuels if they were seen as a good investment.

That said, the transition needs to be fast and will be costly. This raises questions about who is to foot the bill.

That’s the backdrop for a pivotal meeting this week in London at the International Maritime Organization (IMO). The IMO is the United Nations’ agency, made up of 175 nation states, charged with coordinating a response on shipping’s climate pollution. At this meeting, nations will take a series of decisions which will have a profound impact on whether the sector makes a rapid transition away from fossil fuels, or if it continues to limp along on its current high-carbon course.

There are two crucial and interlinked decisions to be taken, and at the moment the proposals range from strong to exceptionally weak. Outcomes could go either way.

Improving efficiency

The efficiency of shipping hasn’t got much attention, even though it’s an important part of reducing emissions. One key policy is the Carbon Intensity Indicator, which measures how much carbon is emitted per tonne of cargo for every mile travelled. The IMO’s current strategy requires improving this efficiency by 40% by 2030, compared to 2008 levels.

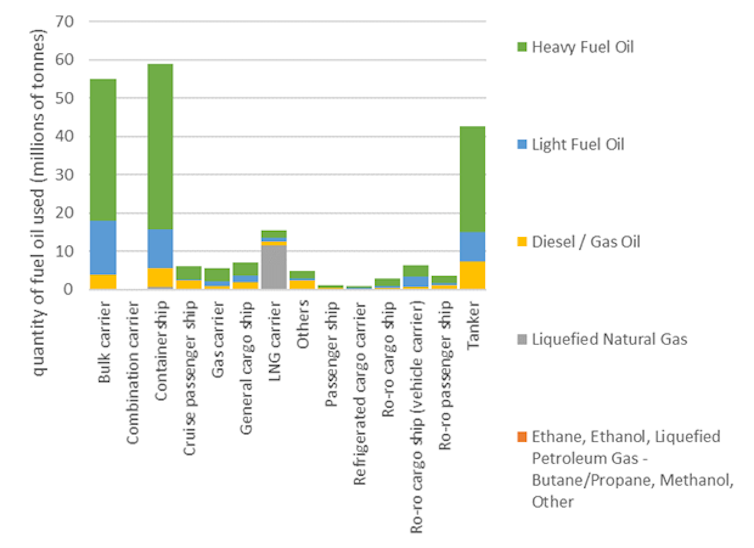

Annual fuel oil consumption (by ship type):

But here’s the problem: global demand for shipping is expected to grow by around 60% in that same time. So even with a 40% efficiency boost, total emissions from shipping could stay the same – or even go up – because so much more cargo will be moved.

Despite this, many countries haven’t updated their policies to reflect this growing demand or to align with the IMO’s updated “30% cuts by 2030” target.

Some countries, including Palau – a Pacific island nation vulnerable to climate change – and the UK, have pushed for stronger action. But there remains a long way to go before the world agrees on an ambitious path forward.

Green energy

The more hotly debated issue is around a fiendishly complicated set of “mid-term measures”. A key part of this is creating a “global fuel standard” – essentially, targets for how much “zero emission” (or “green”) fuel ships must use and by when.

These rules would come with penalties or costs for using polluting fuels, which would effectively put a price on greenhouse gas emissions. Experts have long agreed that putting a price on shipping pollution is the most effective way to encourage cleaner and more efficient practices. But despite nearly 20 years of discussions, countries still haven’t agreed how to do this.

Decisions are further complicated by wrangles over how to fairly distribute the revenues from these penalties.

The good news is that the world is less than a week away from a decision which will put a price on shipping pollution in some form. The bad news is that proposals on the table could easily deliver a weak, uncertain price signal which doesn’t push the industry to invest in more green solutions. And the fuel standard itself might fall short of the ambitious climate targets set in 2023.

Until now, talks on improving shipping efficiency and on pricing polluting fuels have happened separately. A big task at the IMO summit in London is to integrate the two into one coordinated plan.

From a climate perspective, these policies should be judged by whether they will work together to cut shipping emissions by 30% by 2030 (the IMO’s current target).

As things stand, that outcome is still possible – but is now an uphill battle. Agreement this week is crucial and countries will show their true colours. If they can’t agree to agree more ambitious policies it will undermine the IMO’s ability to regulate shipping emissions.

Historically, the IMO tends to take its biggest decisions in the last hours of Thursday in week-long negotiations. Both ambitious and more cautious countries have a lot on the line, as the measure adopted will be legally binding for all of them.

A positive result depends on whether powerful groups such as the European Union line up to support ambitious measures, as as proposed by African, Caribbean, Central American and Pacific countries as well as the UK.

Although countries have agreed on climate targets for shipping, some still refuse to support the policies needed to actually phase out fossil fuels fast enough. That stance much change. If done right, IMO negotiations this week could be a turning point – not just for shipping, but for renewable energy and climate action worldwide.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 40,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

Simon Bullock is a member of the Institute of Marine Engineering, Science and Technology

Christiaan De Beukelaer receives funding from the ClimateWorks Foundation.

Tristan Smith owns shares in UMAS International, that working alongside UCL Energy Institute, provides advisory services on the subject of maritime decarbonisation. My research group is recipient of research funding from UKRI, Climateworks Foundation and Quadratue Climate Foundation. I am on the advisory board of the Global Maritime Forum, and the Strategy Board of the Getting to Zero Coalition - not for profit structures that work across governments and industry stakeholders on maritime decarbonisation.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.