This month marks the 75th anniversary of Pakistan’s independence and of its Partition from British India in a devastating process that uprooted more than 15 million people and resulted in 1 million to 2 million dead. Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs – communities that had coexisted for hundreds of years – all participated in the sectarian violence. Countless people have borne the scars from these events over multiple generations.

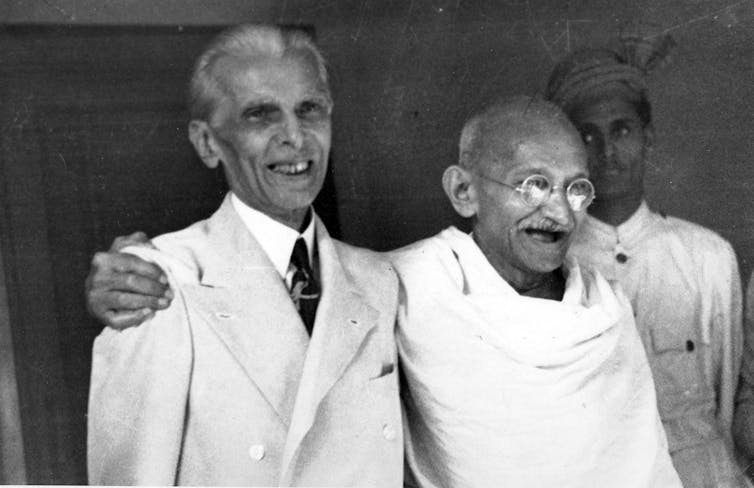

Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan, sought to create a democratic, egalitarian and secular country where the Muslims of the subcontinent, who constituted about 25% of the population, could enjoy full equality. For most of his life, he sought to achieve this equality within an undivided Hindu-majority India. Later he became convinced that a separate homeland was necessary to realize such equality.

Today, widespread and escalating violence against Indian Muslims under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s right-wing, Hindu-nationalist rule seems to confirm Jinnah’s fears.

Jinnah died just a year after Pakistan was born. As a scholar of South Asia, I know that in the years that followed, the military and the business elite consolidated their power and helped shape a country that bears little resemblance to his vision – although many continue to fight for it.

Pakistan today

Ideology and religion are divisive forces in Pakistan today – from sectarian violence against Shia Muslims to the state’s blasphemy laws that authorize a death sentence for anyone who insults Islam. Religion, as interpreted by the state, plays a significant role in politics and governance. An example of its harmful role can be seen in the deterioration of the rights of Ahmadis, members of a religious minority targeted by the state.

Other religious minorities also face discrimination, with Christians subject to particularly harsh treatment. According to Pew Research statistics, 75% of Pakistanis say blasphemy laws are necessary to protect Islam, while only 6% say blasphemy laws unfairly target minorities.

Pakistan also remains on a turbulent political and economic trajectory. The army has been in direct control of the state for most of its existence, with four military coups and decades of military rule since 1958. The military and notorious intelligence services remain in direct control of domestic and foreign policy, making decisions to protect their power and economic interests, including vast commercial holdings.

Economically, Pakistan has lagged behind other developing countries, with debt as high as 71.3% of its GDP. Inequality is high, with the top 10% of households owning 60% of the national wealth, and the bottom 60% owning just 10%.

The elite evade taxes on a massive scale, contributing to the country’s economic instability. While millions live in dire poverty and hunger, the government’s spending to mitigate poverty is among the lowest in the region. Dissidents, human rights activists and journalists face censorship and repression.

Jinnah had hoped for much better.

Jinnah: An advocate for Muslims in British India

Born in Karachi in 1876 to a Muslim family, Jinnah was first educated at a local Muslim school and later at Karachi’s Christian Missionary Society High School.

At 16, Jinnah was sent to London, where he decided to study law. After returning to India, he established himself in Bombay as a successful and eloquent lawyer.

Jinnah joined the Indian National Congress in 1906, becoming part of the largest Indian political party organizing for independence from British colonial rule. At this time, he was the foremost proponent of Hindu-Muslim harmony in India and pursued a strategy of a unified front against the British.

He considered himself “a staunch Congressman” and rejected political organizing that separated Muslims and Hindus in India. Accordingly, Jinnah delayed joining the All-India Muslim League, the political party formed to represent the rights and concerns of the Muslims of British India, until 1913. For years he remained a member of both parties.

Jinnah’s concerns over Hindu nationalism

Jinnah’s faith in the Congress party would wane, and he resigned in 1920. He was increasingly concerned with Congress’ growing emphasis on India’s Hindu identity and the lack of political representation for the country’s Muslim minority.

Jinnah was also deeply disturbed by the emergence of right-wing Hindu nationalist groups like the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, or RSS, a violent paramilitary group that drew inspiration from European fascist parties, opposed Muslim-Hindu unity and increasingly sought to force Muslims to convert or leave India.

In 1934, Jinnah was unanimously elected as the president of the Muslim League, and he continued to advocate for the rights of Muslims in a unified India. He did not embrace dividing the Indian subcontinent into separate Muslim-majority and Hindu-majority areas until the 1940s.

In this period, escalating sectarian violence stoked by both Hindu and Muslim right-wing groups, and Congress’ refusal to accept a federation in which Muslim-majority regions enjoyed greater political representation, contributed to foreclosing an alternative to partition. During this period, Jinnah stressed that Muslims would never enjoy security and full equality in the Hindu-majority nation.

Jinnah eventually led the Muslims of India to form a nation of their own with the creation of Pakistan in 1947. He insisted that this new nation be a secular democratic country with equal rights for all who resided there.

Jinnah’s vision for a secular Pakistan

Jinnah emphasized the necessity of secular education to improve social and economic conditions in the Muslim community, argued for equality between the sexes and advocated for the discarding of the parda, or veil.

Jinnah did not write a book or memoir, but his speeches give an insight into his vision for Pakistan. Notably, his speech a few days before becoming Pakistan’s first president, delivered on Aug. 11, 1947, expressed his secular aspirations for the newly formed country. In it he stressed: “You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other place of worship in this State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion or caste or creed – that has nothing to do with the business of the state.”

Four days later, on Aug. 14, 1947, British India was divided into the independent nations of Pakistan and India. As the first president of Pakistan, Jinnah again emphasized his secular vision for the new country, saying, “We are starting in the days where there is no discrimination, no distinction between one community and another, no discrimination between one caste or creed and another. … We are all citizens and equal citizens of one State.”

Jinnah’s dream unrealized

Jinnah’s achievement remains a significant milestone of the 20th century. But 75 years later, Pakistan is far from the country he envisioned.

People from the region, nostalgic for a unified country and cognizant of the suffering during Partition and beyond, sometimes express that it might have been better if they had not been divided based on their religious identity but had instead continued the struggle for a pluralistic society with equal rights for all. Others maintain that Jinnah was right to conclude that Muslims in India were bound to face continued violence and be treated as second-class citizens in a Hindu-majority country.

What is certain is that Jinnah’s dream of a compassionate homeland for the minorities of the subcontinent remains unrealized. But glimmers of it have lived on in movements and people who have gone on to dream of a more equitable, inclusive and just Pakistan.

For example, Christian and Muslim landless farmers in the Peasant Movement, one of the largest and most successful land rights movements in South Asia, have resisted violent efforts to quash their demands for a more equitable society. Some 80,000 lawyers were part of the Lawyers Movement, which challenged the power of the military and fought for a free and independent judiciary. And individuals such as human rights activist Sabeen Mahmud have paid with their lives for their dream of a just and pluralist Pakistan.

And while today’s Pakistan is far from Jinnah’s vision, the work of these people and movements reflects the famous words of Pakistan’s most celebrated revolutionary poet, Faiz Ahmed Faiz: “We must [continue to] search for that promised Dawn.”

Farah N. Jan has received funding from Perry World House at the University of Pennsylvania. Thanks to Leili Kashani for contributing ideas and edits to this piece.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.