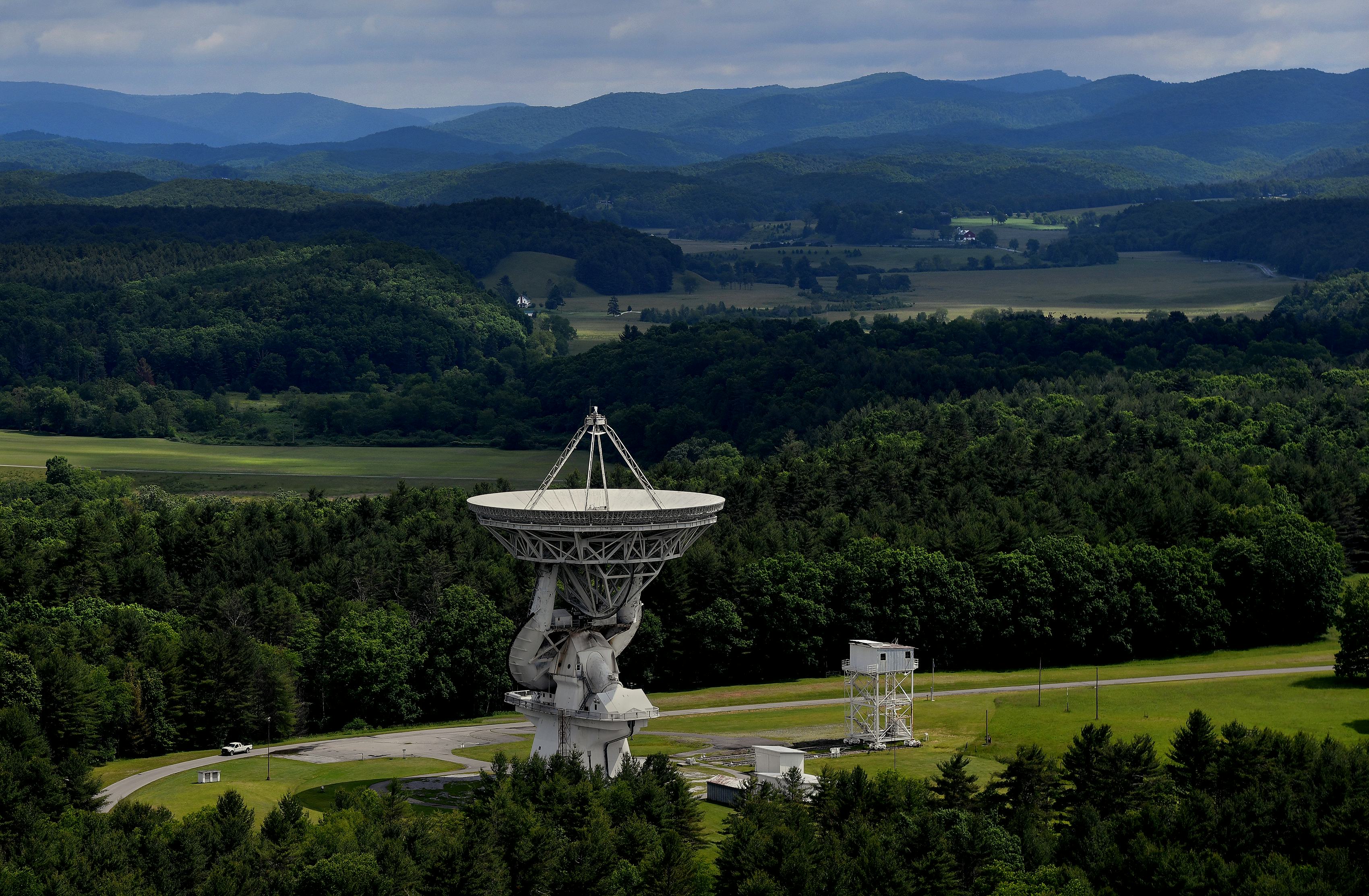

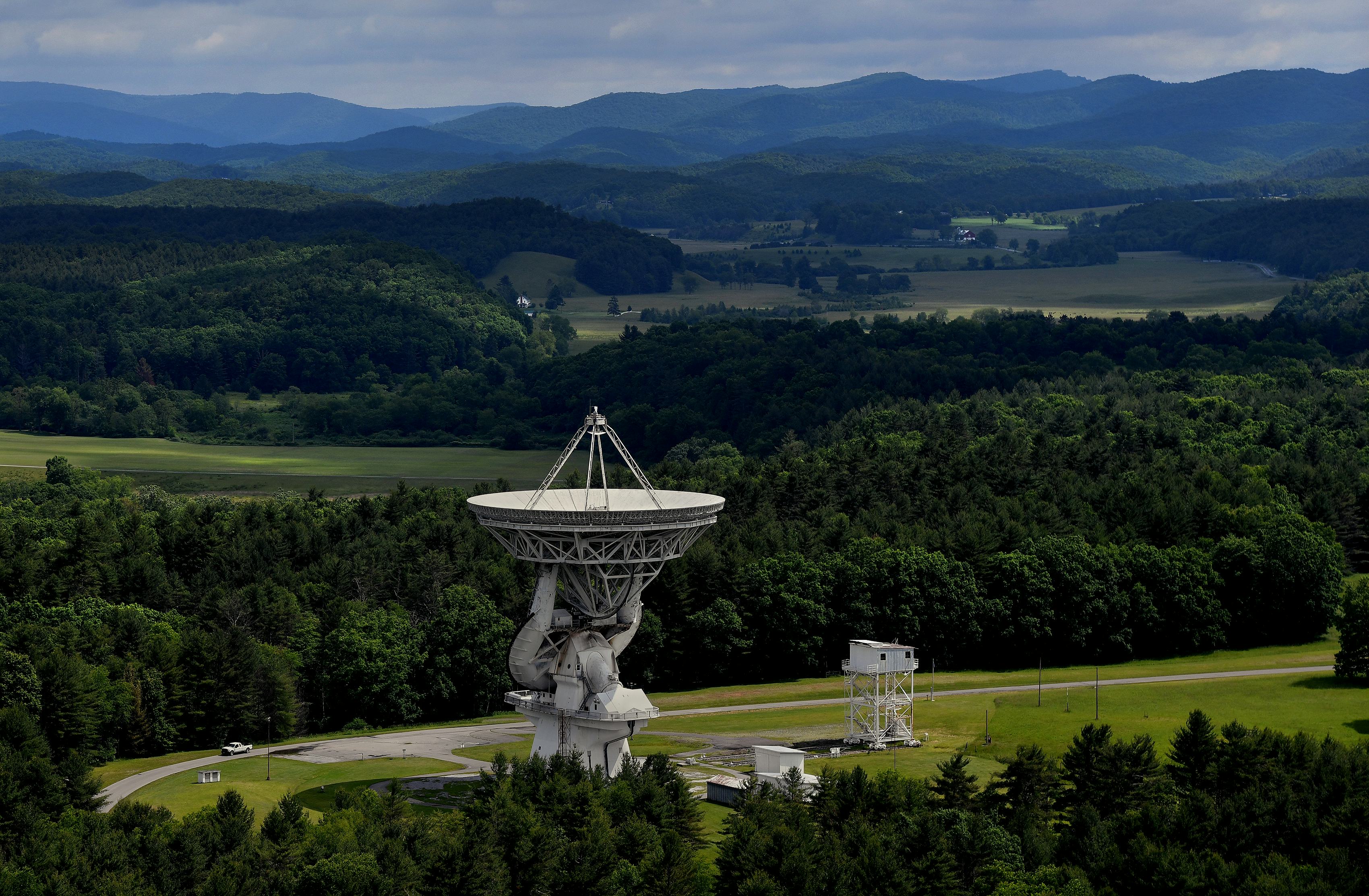

A team of astronomers recently used the Green Bank Telescope, a radio observatory in West Virginia, to check an important corner of our Solar System for signals from an alien probe. No, really.

Astronomers Nick Tusay and Macy Huston of Pennsylvania State University recently pointed the Green Bank Telescope at a patch of sky where, 500 times the distance of the Earth from the Sun (known as an astronomical unit, or AU), radio waves from Alpha Centauri might converge at a focal point after being curved and magnified by the effects of the Sun’s gravity. They were hoping to eavesdrop on hypothetical aliens, who could — in theory — take advantage of this phenomenon, called gravitational lensing, to communicate with their interstellar probes.

What’s New — Just like a magnifying lens here on Earth, a gravitational lens has a focal point: a spot where all the light coming through the lens meets again on the other side. That's where the magnified image — or signal — will be at its strongest and clearest. For light or radio waves being gravitationally lensed by our Sun, that focal point is about 550 AU from the Sun, directly opposite the place the signal is coming from.

In other words, if you were a mission planner at an alien space agency in the Alpha Centauri System, and if you wanted to communicate efficiently with a science probe you were sending to our Solar System, you'd consider parking your probe about 550 AU from the Sun, on the side directly opposite Alpha Centauri. There’s a focal point for pretty much any star you can think of — to find it, just draw a straight line from the star through our Sun.

And that’s what Tusay and Huston wanted to look for – radio signals from an alien version of Juno or the Voyager spacecraft, parked in a spot so distant that we might not otherwise notice it.

“In contrast to classical radio SETI searches for intentional messages sent toward Earth from interstellar distances, this method primarily attempts to eavesdrop on communications between two technological structures,” wrote Tusay and Huston in their pre-print paper.

Here’s the Background — We’ve known about this handy quirk of physics in our own backyard since physicist Albert Einstein predicted it during the early 20th century. But it was astronomer Frank Drake, of Drake Equation fame, who first suggested putting a probe at one of these natural focal points, where it could listen for signals from neighboring star systems magnified by the Sun’s gravitational lens.

Other astronomers have suggested using the Sun’s gravitational lens for more traditional kinds of science, like searching for exoplanets. So there’s plenty that Earthling astronomers could do with a spacecraft parked here, where the light curved by the Sun’s gravity converges on a single point in space. But what Tusay and Huston boldly suggest is that humans aren’t the only ones who might have a use for those particular bits of heliocentric real estate.

A focal point would be a convenient place to put a science mission — an alien version of the Cassini spacecraft, maybe — to study our Solar System or even try to contact us, because signals from home would be naturally amplified by the gravitational lens. Tusay and Huston also suggest that if a hypothetical alien civilization really had its stuff together, enough to explore or even settle in multiple star systems, then the could put communications nodes at each star’s gravitational lens focal points.

For example, let’s go back to your imaginary job at the Alpha Centauri Space Agency. If you wanted to communicate with a spacecraft in a star system like Epsilon Eridani, it might be more efficient to route that message through a relay in our Solar System. You ping the communications node at the Alpha Centauri focal point around the Sun; that node pings one orbiting Epsilon Eridani at its gravitational lens’ focal point opposite our Sun.

“This strategy is commonly used for communication networks around the Earth, such as the Internet,” write Tusay and Huston.

We usually think of SETI as studying other star systems, looking for signals, or even for alien technosignatures that might be visible across cosmic distances. But there’s another kind of SETI called “artifact SETI” or “Search for Extraterrestrial Artifacts (SETA)” that focuses on “the search for any material artifacts that may be sent by extraterrestrial intelligence during a long-term galactic exploration effort.” In other words, looking for stuff wandering aliens might have left in our own Solar System instead of trying to spot their homeworlds from afar.

A lot of SETA involves asking the same kinds of questions as traditional SETI, like “What should we be looking for?” A previous study used simulations and models to figure out what kind of probe would be most likely: something between 1 and 10 meters diameter, set 550 AU or more from the Sun, receiving and broadcasting in a specific range of radio frequencies.

What’s Next — If an intelligent group of starfaring aliens has built an interstellar version of the internet using gravitational lens focal points, Tusay and Huston suggest, there should be probes around our Sun at the focal points associated with nearby stars.

“If there are probes within the Solar System connected to such a network, we might detect them by intercepting transmissions from relays at these foci,” write Tusay and Huston.

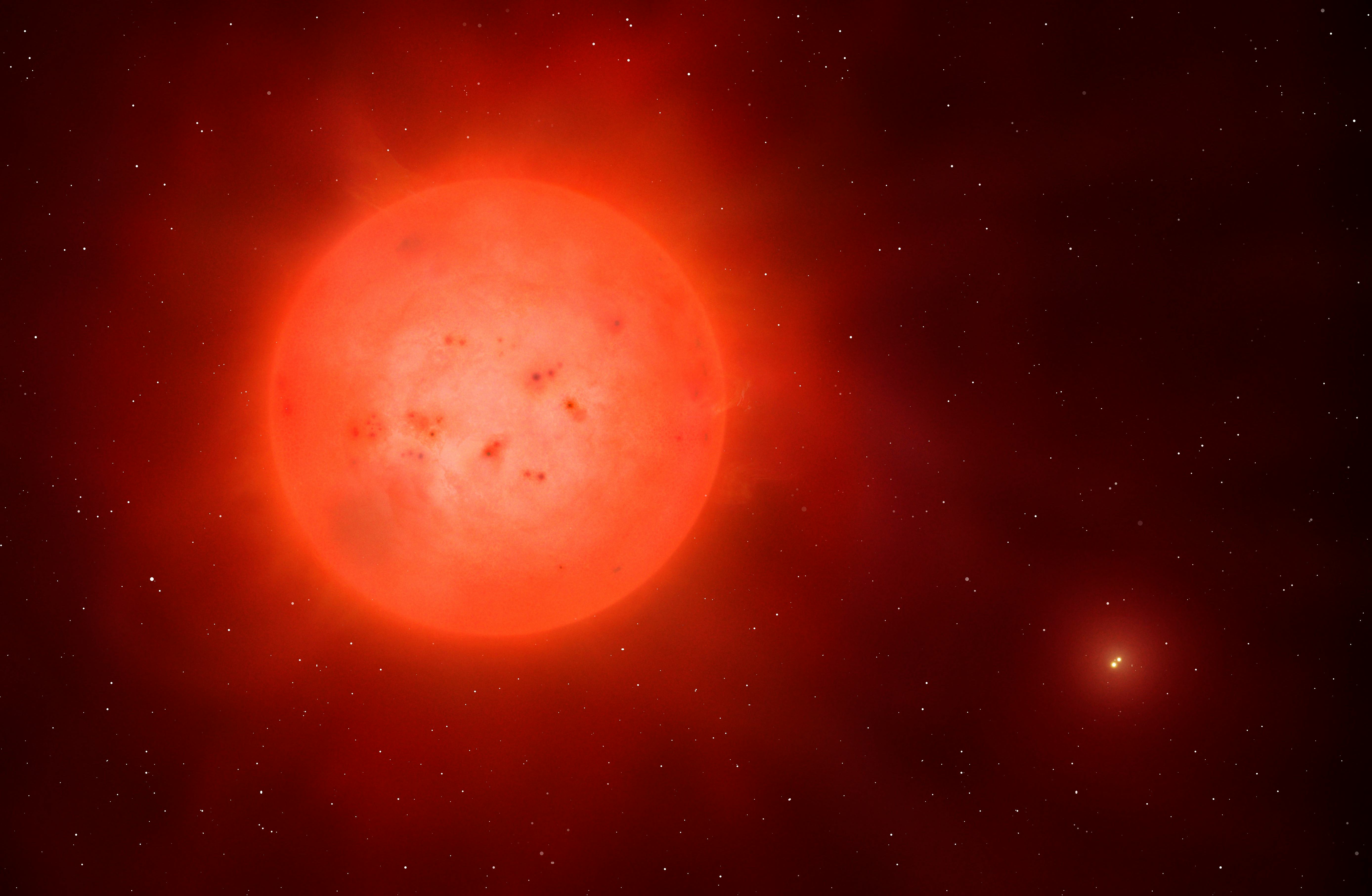

They started with the focal point opposite Alpha Centauri, and perhaps it’s no surprise that they didn’t find anything. After all, we know of just three exoplanets and one exoplanet candidate in the Alpha Centauri system – three of which actually orbit red dwarf Proxima Centauri, and only one of which is in the star’s habitable zone. It’s not necessarily the first place you’d look for signs of an alien space program, except that it’s close by, just 4.4 light years away.

Tusay and Huston suggest SETI researchers performing similar searches at the focal points associated with other planets, and at different distances and radio frequencies.

You never know; the call just might be coming from inside the Solar System.