One of the largest canyons in our Solar System carved its way through several layers of ancient volcanic eruption debris, a recent study reports.

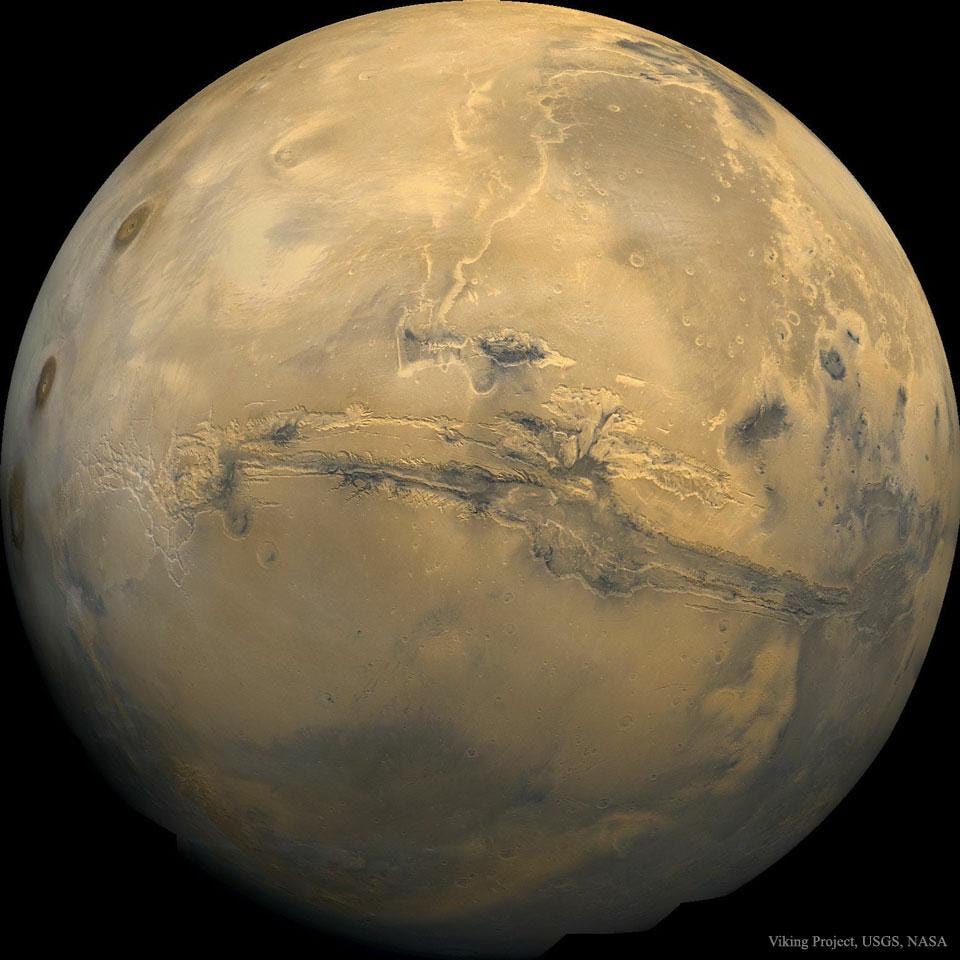

Valles Marineris is a titanic network of deep cracks in the crust of Mars, stretching a quarter of the way around the planet, or roughly 4,000 kilometers (2,500 miles), near the equator. The canyons are eight kilometers (five miles) deep at some points. A recent study discovered traces of an ancient volcanic eruption in the walls of Valles Marineris, made of a mineral rarely seen on Mars in such large amounts. The ancient volcanic deposit could add an unexpected new chapter to the tumultuous history of the planet.

The researchers published their work in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

What’s New — Using an instrument aboard NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, called the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars, University of Lorraine planetary scientist Jessica Flahaut and her colleagues spotted a group of minerals called plagioclase feldspar in the walls of in Valles Marineris. The instrument split visible and infrared light from the surface into the individual wavelengths that make it up. That spectrum of wavelengths holds information about a rock layer's chemical composition.

Plagioclase feldspar is an igneous rock, which means it’s basically cooled lava or magma. Most of the outcrops of plagioclase feldspar (which we’re going to just shorten to “feldspar,” here, but it’s worth knowing that there are other types) found on Mars so far have been made of magma that cooled and solidified while it was still deep beneath the Martian surface, and only saw the light of day thanks to meteor impacts, which unearthed buried layers of rock.

But in the walls of Valles Marineris, among the middle layers of rock, Flahaut and her colleagues saw a two-meter-thick layer of feldspar that stretched for several kilometers. It’s a fairly flat layer, tilted slightly northward, and Flahaut and her colleagues say its shape and size match what they’d expect if the feldspar had erupted onto the surface of Mars at some point, either as a lava flow or a layer of volcanic ash.

Volcanic rock on Mars is no surprise; we already know the planet has an eventful geologic history, and it’s home to the largest volcano in the Solar System, Olympus Mons. But plagioclase feldspar, in particular, is a rare find — one that could tell us some interesting things about what Mars’ crust is made of and how it formed.

Why It Matters — The newly-discovered feldspar layer lies beneath several kilometers of other lava flows in the walls of Valles Marineris. Their chemical spectra suggest that they’re made mostly of a volcanic rock called basalt, which is the cooled, solid version of what was once very fluid lava rich in magnesium and iron. Most of the volcanic rock on Earth and on the Moon is basalt, so it’s not surprising to find layers of it on Mars, too, especially in an area like Valles Marineris, where there was so much violent geological upheaval in the distant Martian past.

It’s much rarer to find feldspar on Mars, especially in such a large deposit. In part, that’s because the mineral is challenging to detect with infrared spectrometers.

Plagioclase feldspar actually describes a group of closely related minerals, which contain different amounts of sodium and calcium. If planetary scientists like Flahaut and her colleagues can gather higher-resolution data and learn exactly which minerals make up the ancient feldspar deposit in Valles Marineris — and see whether it oozed across the landscape as lava or rained from the sky as volcanic ash — they can piece together another chapter of Mars’s story.

At the moment, scientists still aren’t entirely sure what types of rock the Martian crust is made of, or exactly how it formed. It’s possible that Mars’s crust was once the top layer of a planet-spanning ocean of magma, which cooled and hardened; that’s how the lunar crust formed about 4.4 billion years ago. But the most current models suggest that what happened on Mars was more complicated; about 100 million years after Mars formed, the planet’s inner layers may have endured something called “mantle overturn,” which happens when the deeper layers of the mantle rise upward, forcing the upper layers down. That would have melted rocks rich in magnesium, which eventually cooled to form basalt in the Martian crust.

The details of what happened to create the surface of Mars we see today are written in local rock outcrops all over the planet — including many that have yet to be studied in detail.