Three prime ministers – Boris Johnson, Liz Truss and, now, Rishi Sunak – in less than two months. The leadership tumult in the cradle of parliamentary democracy, Westminster, is a source of macabre fascination.

Sunak faces a Herculean task to resurrect the Conservative Party’s collapsed political fortunes amid a post-Brexit Britain convulsed by economic crisis. If Sunak is to survive, he will need to heed the lessons of the failings of the Johnson and Truss administrations, their premierships laying bare many of the dysfunctions of early 21st century political leadership.

Johnson governed in the style of a modern day populist, performative rather than substantive, shambolic of process, scandal ridden and evasive of accountability. He lied habitually, his cruellest deceit the promise of Brexit glory for ordinary Britons.

Read more: There’s something wrong with British politics. It’s called the Conservative Party

The truncated Truss experiment was perhaps even more abject. Lacking broad-based party support, she governed in the fashion of an ideological clique. Fatally, she and then-Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng seized the opportunity to impose in a mini-budget the trickle down economic ideas they had expounded as ambitious young backbenchers in a 2012 neo-liberal manifesto Britannia Unchained.

Headlined by unfunded tax cuts favouring the wealthy, the mini budget took no account of the financial or political consequences. There followed bedlam on the markets and a crash of the Conservative Party’s position in the polls.

Australia, of course, has had more than its share of leadership excesses and upheavals over the past decade and a half. But could that phase be passing? It is instructive to compare the early days of Anthony Albanese’s prime ministership to the chaos at Westminster. By contrast, Albanese’s administration seems a model of sound – dare we say, grown up – governance.

What is perhaps most refreshing about the Albanese government is that it is a collegiate, team outfit rather than a one-man band. Yet Albanese’s leadership is clearly key. In that context, it is striking that he exhibits many characteristics of past successful prime ministers.

First of those characteristics is a precocious interest in politics. Like John Howard and Paul Keating, Albanese’s involvement in politics began as a teenager. There is nothing wrong with having a long political resume so long as it is supplemented by other qualities.

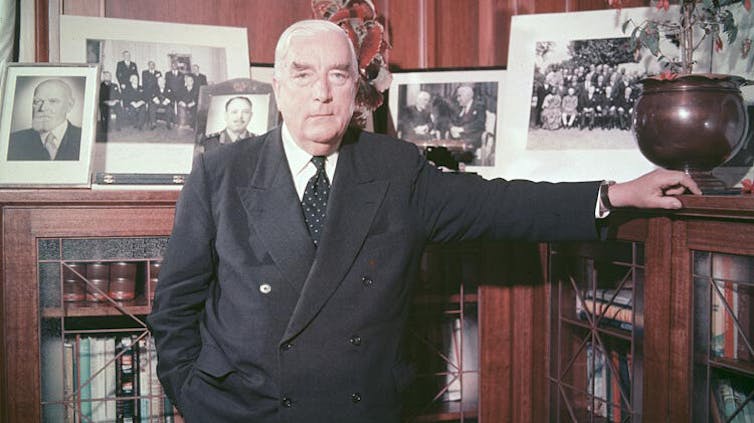

Second is having experienced a lengthy parliamentary apprenticeship and encountering adversity along the way. This builds resilience and smooths out temperament. Our best prime ministers have generally tasted bitter failure on the road to triumph. Think of Robert Menzies’ first disastrous government that ended in humiliating resignation. Albanese waited a quarter of a century in the parliament for the prime ministership, and endured the awful days of the Rudd-Gillard internecine leadership wars.

Third, is being a creature of the political party and having a deep knowledge of its culture. Albanese is a lifelong member of the ALP: he is intimately acquainted with its nooks and crannies. It is not enough, however, to be a cipher of the party: a successful leader must retain a degree of autonomy from the party and be willing to defy it at times. Consider Bob Hawke and Keating dragooning Labor to the task of internationalising the economy. Albanese showed something of that ability while opposition leader by staring down internal critiques of his so-called small target strategy.

Fourth, and this springs from a lengthy apprenticeship, is a keen understanding of, and respect for, the processes and institutions of governance (such as the public service, cabinet, private office), combined with a canny ability to manage them. Hawke and Howard were masters in this respect. Fundamental here is an appreciation that one cannot rule solo: government must be a collective enterprise. Leadership is about distributing authority and orchestrating an ensemble of actors.

Fifth is an ability to project authenticity – that rare ineffable but invaluable leadership quality. Albanese is not blessed with Hawke’s seductive charisma but boasts something of Ben Chifley’s rough-hewn sincerity, which makes him relatable.

Sixth is a sense of judgement and timing (something Truss spectacularly did not have): a pragmatic intuition of when to push and when to parry. Consider Howard holding off on the GST during his first term before striking out on his great tax reform adventure. We see Albanese prioritising the Indigenous Voice to Parliament while, conversely, he has for now shut down debate on the stage three tax cuts.

Read more: Grattan on Friday: Should Anthony Albanese keep his word on the Stage 3 tax cuts?

Seventh is a mastery of communication. Here the jury is out on Albanese. Will he have a medium in which he excels (for example John Curtin and Menzies on radio, Hawke on television, Keating via the press gallery and Howard on talkback radio)? Journalist Katharine Murphy has written that Albanese’s early days in power have exuded calmness, but that the cyclone of media disruption will eventually catch up with him. The question indeed lingers whether Albanese will be the first leader of the digital age (Rudd onwards) to tame the media beast.

Eighth is having a road map for office. Though hardly Whitlamesque of scale, Albanese has laid out a reform program that offers plenty to achieve in a first term.

There is a final indispensable ingredient for prime-ministerial success: good fortune. Our most celebrated national leaders have been lucky generals. Albanese has come to office in unpropitious circumstances – surging inflation and a turbulent geopolitical environment. But able leaders transform crisis into opportunity, such as Curtin in the second world war laying the foundations of a new economic and social settlement.

There are still formidable barriers to Albanese guiding Australia to renewed political stability, not least the dissolving moorings of the traditional party system. Yet just maybe he is the prime minister whose legacy will be the country’s next big settlement.

Paul Strangio does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.