artin Scorsese had a lump in his throat and a cold ache in his belly as he arrived at the Venice Film Festival. It was 1988, two years before his gangster opus Goodfellas. But as his private jet touched down at Marco Polo airport, motormouthed mobsters from Brooklyn were the last thing on his mind.

He was in Venice to unveil his transgressive retelling of the New Testament, The Last Temptation of Christ. Amid fears of an ugly stand-off with hardline Christians, there were plans for 100 mounted police to create a cordon around the Palazzo del Cinema di Venezia on the evening of the screening.

This seemed entirely prudent. Several hours ahead of the premiere, an excommunicated archbishop had staged a protest march through St Mark’s Square. He was followed by a wooden cross emblazoned with the words “Scorsese’s film is blasphemous”.

The director’s nerves were on edge, then, as he strode through the lobby of his hotel, across from the Palazzo. Those jitters grew even sharper when a young man sprang from the shadows and proffered a hand. A scrum of security guards descended on the guy, whom Scorsese recognised as an up-and-coming actor in consideration for his next picture.

“I’d seen Ray Liotta in Something Wild, Jonathan Demme’s film; I really liked him,” Scorsese would tell GQ magazine in 2010. “I had a lot of bodyguards around me. Ray approached me in the lobby and the bodyguards moved toward him, and he had an interesting way of reacting, which was he held his ground, but made them understand he was no threat. I liked his behaviour at that moment.”

Scorsese’s next picture was, of course, Goodfellas. And Liotta’s chutzpah paid off, with the director overruling his reluctant producers and casting the unheard-of 34-year-old in the lead. As Goodfellas marks its 30th anniversary on 19 September, the actor – who had been in Venice with his indie movie Dominick and Eugene – will surely look back on that encounter with Scorsese and thank his stars he had been so forward.

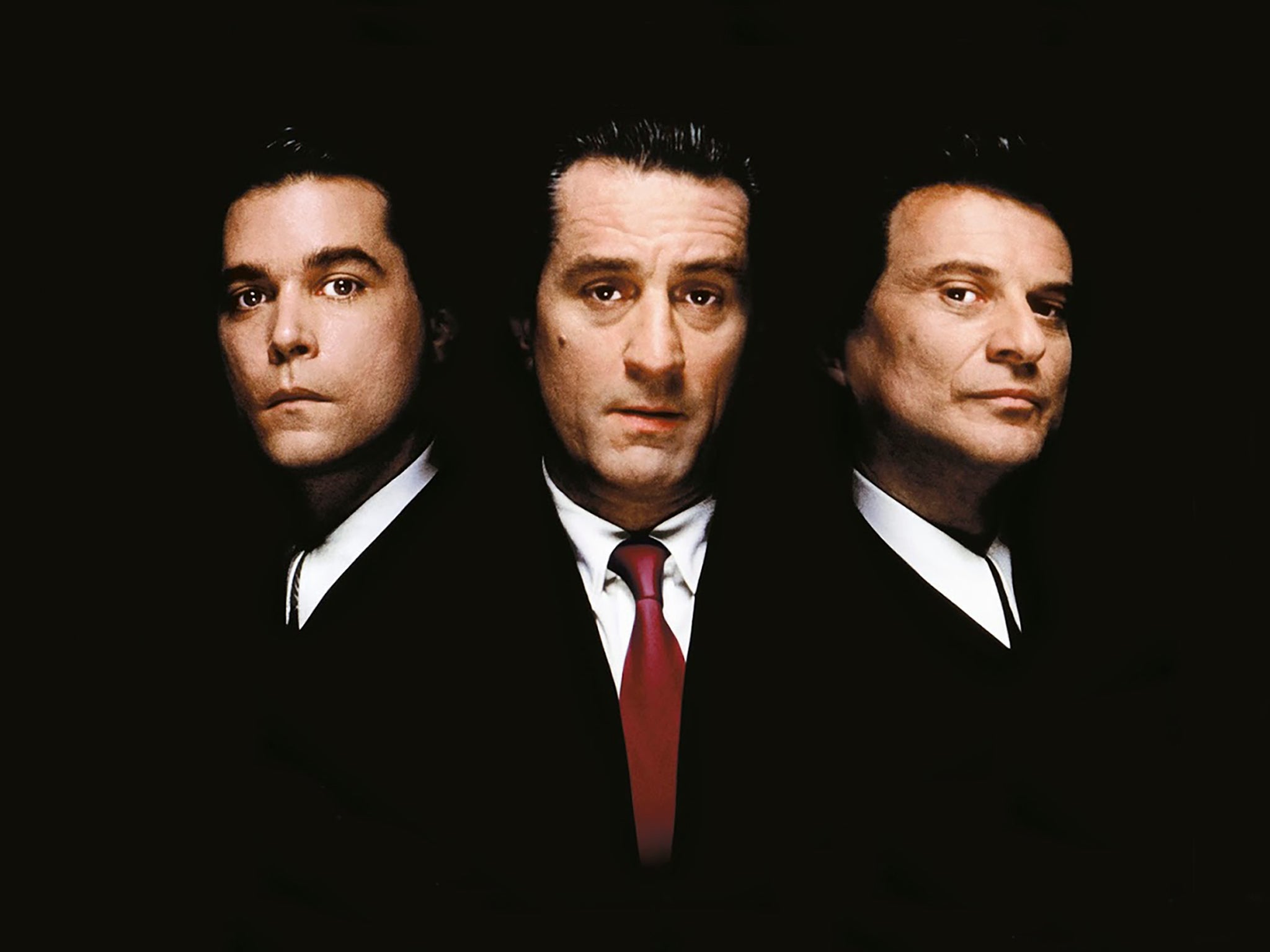

Goodfellas, it hardly needs pointing out, is a masterpiece. Robert De Niro and Joe Pesci are never better as the grizzled mob mentors to Liotta’s gangster newcomer, Henry Hill (De Niro had fretted he was too old for his part, which was offered originally to John Malkovich). The violence is shocking, the expletives never-ending. Goodfellas would set a new record with its 300 f-bombs – a total Scorsese himself would surpass with 1995’s spiritual sequel Casino. But it is also uproarious to watch and often hilarious.

That is arguably why it eclipses The Godfather Parts One and Two and Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America. These are important, austere gangster epics, caught up in their own tragic grandeur. Goodfellas is, by contrast, a hoot, a caper, a romp. Many of its best scenes are essentially comic. Morris “Morrie” Kessler’s gonzo wig commercials. The exasperation of Henry’s mob pals as he separates from his wife. Hill’s cocaine-fuelled paranoia in the movie’s closing third. Scorsese understood the best way to reel in an audience into this dark and unpleasant world was with jokes and absurdist riffs.

The gags also underscored Scorsese’s determination not to make just another mobster flick. The genre had held little interest for the director through his career. True, he’d drawn on his hard-knock upbringing in New York’s Little Italy in 1973’s Mean Streets. And he’d touched on the dark side of New York with Taxi Driver three years later. But having spent time around “wise guys” as a kid, the adult Scorsese had wanted to get as far from that world as possible.

One reason was that he was haunted by the possibility that, had things turned out a little differently, he might have himself ended up in the shiny shoes of Henry Hill. Twinkle-eyed Henry was based on a real-life Brooklyn mobster of the same name, affiliated to the Lucchese crime family (one of the New York underworld’s “Five Families”). Hill had entered the witness protection programme in 1980, having become an FBI informant. However, he was expelled seven years later after being found guilty of cocaine trafficking.

That’s how it went with wise guys, goodfellas… whatever you wanted to call them. Gangsters had ruled Little Italy when Scorsese was growing up. One of his closest friends was the son of a local boss. Scorsese suffered asthma and so spent most of his time indoors watching TV. Had he been out on the streets, as young Henry is at the start of the film, who knows where he might have wound up?

Comedy aside, Goodfellas took all sorts of risks. Consider its use of Henry’s voiceover, generally regarded in Hollywood as a cheesy contrivance. Not five minutes in, we see Tommy (Pesci) and Jimmy (De Niro) stabbing and shooting a bloodied man in a car boot. Scorsese next zooms in on Henry’s face, which in the half-light, has a devilish red glare. And then comes one of the most famous monologuing lines in cinema. “As far back as I can remember,” says Liotta,” I always wanted to be a gangster.”

Scorsese wrote the script with Nicholas Pileggi, who’d chronicled Henry Hill’s rise and fall in his 1985 bestseller Wiseguy (which was to have been the title of the film until it was pointed that the name clashed with that of an 1980s TV series). The experience was a baptism for Pileggi. He was astonished by the intensity with which Scorsese could write a scene and by the director’s obsession with momentum.

Above all, Scorsese believed, a film needed to crack along. The opening set-piece, for instance, was originally intended to appear halfway through. It followed the barroom attack on Frank Vincent’s Billy Batts, who brings down a world of trouble when reminding Tommy of his days as a shoe-shine boy. “Now go home and get your f***in’ shinebox,” says Billy. Tommy, Henry and Jimmy beat him unconscious and bung the body in the boot – only to be surprised to later discover that Batts is still alive, wheezing through his blood.

Something about the setup-and-delivery nagged at Scorsese. It was, he eventually realised, overly linear. Everything happened just as you would expect. So he put Batts’s death up top and paired it with the “I always wanted to be a gangster” line. It made for an explosive opening. It also let you know what you were in for.

“So many times voiceover is used to patch a crack in the script and it doesn’t work,” Pileggi said in the 2004 documentary, Goodfellas: The Making of a Classic. “Scorsese loved the idea of these guys driving around with a body in the boot [as a way to begin the story].”

Pileggi was struck, too, by Scorsese’s use of improvisation. One of the conditions under which Joe Pesci had agreed to do Goodfellas was that he could share some of the anecdotes he’d picked up around mobbed-up guys in New Jersey as a teenager. The most famous example is the “How am I funny?” scene, in which Tommy turns on Henry after the younger gangster playfully commends his colleague’s ability to tell a joke. “Joe was working at some restaurant in the Bronx or Brooklyn,” Liotta said at a public screening of Goodfellas years later. “He said to some wiseguy, ‘You’re funny,’ and the guy kind of turned it on him.”

This exchange was sketched out in secrecy by Scorsese, Pesci and Liotta. The director made sure none of the supporting cast were in on it. When the cameras were rolling, he used medium takes without close-ups, so as to capture their astonishment in real time.

The approach stunned Pileggi – who was even more shocked to subsequently win acclaim for “writing” an exchange in which he had absolutely no involvement. He received another lesson in Scorsese’s remarkable ability to get the most from his cast when he witnessed the director tapping into the anger Liotta was feeling over the ill-health of his mother. She would die from cancer during the filming at age 63 and Liotta carried the emotion around with him every day.

Those feelings boiled over in the sequence in which Henry pistol-whips a neighbour of his girlfriend, Karen (Lorraine Bracco), after he disrespects her. “Ray was boiling with rage. He stayed away from me, across the street, and he kept that going for take after take,” Mark Evans Jacob, who played the quivering boy next door, recalled to GQ. “We tried to keep the anger controlled, but one take got a little too close and I got hit.”

Scorsese wasn’t always the most approachable on set. Eyewitnesses say he and De Niro had a conspiratorial working relationship, spending much of the time in whispered conversation. Even Liotta, nominally one of the stars, felt excluded. That isn’t to say the director wasn’t enjoying himself. The celebrated six-minute tracking shot that follows Henry and Karen’s entry to the Copacabana nightclub, for instance, was essentially a mischievous attempt to one-up Brian De Palma.

De Palma had won praise for a bravura Steadicam sequence in The Untouchables (1987). As a quiet wink at his friend and rival, Scorsese used an even longer one for the Copacabana. “Brian De Palma had just done this incredibly long Steadicam shot in The Untouchables, and Marty said it would be funny to try to do it one minute longer than De Palma’s,” actress Illeana Douglas (mob wife Rosie) said to GQ. “The world perceives this as ‘Oh, the Copacabana scene!’ But what it really is, is directors behind the scenes having fun f***ing with each other.

The Copacabana also serves a more serious purpose, however. The sequence communicates the degree to which Karen is seduced by Henry’s lifestyle. Scorsese’s genius was to put us in Karen’s shoes and to essentially force us to share her awe. “Marty found a way to have Henry Hill not only impress his date, Karen, but to show the audience why the world of Goodfellas was so attractive and glamorous,” wrote producer Irwin Winkler in his 2019 memoir, A Life in Movies.

The movie’s authenticity, meanwhile, was heightened through the use of real-life mobsters as extras. One of the “actors” started passing counterfeit dollars around set. Another, NYPD detective Louis Eppolito, was later convicted of carrying out eight mob hits.

Everyone involved knew they were making something special. The exception was the studio, which feared it had a bomb on its hands. Test audiences didn’t really get Goodfellas. The biggest issue appeared to be the violence. In previews, audience members had walked out during the scene in which Tommy stabs Billy Batts seven times as he bleeds in the boot. Scorsese agreed to reduce it to four stabs, with the final three knife-plunges heard but not depicted.

“It’s hard to really blame them for their nervousness, given the audience reaction,” Winkler would write. “Some films just need the media, critics and word of mouth to let the audience know a film is special. That was the case with Goodfellas and ultimately we barely changed much from the terrible preview screenings.”

As Winkler expected, the critical response was ecstatic. “Goodfellas looks and sounds as if it must be absolutely authentic,” raved The New York Times. “No finer film has ever been made about organised crime – not even The Godfather,” wrote Roger Ebert in the Chicago Tribune. “The fastest, sharpest two-and-a-half-hour ride in recent film history,” agreed Time, picking up on Scorsese’s obsession with cracking the whip.

Goodfellas was nominated for six Oscars but would triumph in just one category. Joe Pesci, receiving the award for Best Supporting Actor, gave the shortest acceptance speech in Academy Awards history. “It's my privilege. Thank you,” he said and was gone. The truth is that the privilege was all ours. Scorsese had not only reinvented the gangster flick with a film both funny and unflinching (to say nothing of paving the way for The Sopranos). He also gave us perhaps the best movie of his career and a true modern classic.