Midway through last week, I had a long conversation with a man called Steven Wright, who lives in Suffolk. The previous day, I had spent a lot of time piecing through government documents and official statistics as I tried to make sense of the huge crisis engulfing some of the most crucial elements of England’s education system. But as usual, nothing came near the visceral impact of first-person testimony.

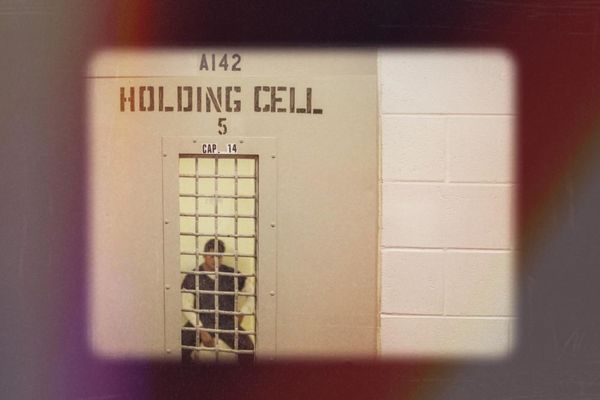

Wright is a widower, and the adoptive father of two teenagers, both of whom live with the effects of foetal alcohol spectrum disorder: “basically, brain damage due to alcohol exposure in the womb”. His 16-year-old son, he explains, is more severely affected than his 14-year-old daughter: having crashed out of several “inflexible” state schools that did not provide the support his condition demands, he is being tutored at home for 25 hours a week, up from only 12 when the arrangement began. “He is effectively isolated from his peers, almost in solitary confinement,” Wright told me. “He’s had no chance to take qualifications of any kind. There’s no plan for the future at all … It’s been an absolute disaster.”

What makes his family’s predicament all the more painful is the fact that back in 2018 he successfully fought for his son to get an education, health and care plan (or EHCP), an official document that – in theory, at least – legally compels his local authority to provide help, from speech and occupational therapy to assistance with the social aspects of school. But any support has been patchy and sporadic. Last year, for example, he discovered that the person who had been dispatched to their home to tutor his son was not even a qualified teacher. As a result, he has spent huge amounts of time battling Suffolk county council, often to no avail.

Yet even as he was fighting for the bare minimum, a particularly pernicious story about England’s special needs crisis was taking shape: the idea that as the system buckles and councils teeter on the financial brink, the people most responsible are the parents who tirelessly fight for their kids. Rising need has been recast as “demand”. Gillian Keegan, our ninth education secretary in 10 years, has suggested that parental appeals against council decisions to refuse Send (special educational needs and disabilities) support – at the last count, 96% of which were upheld – amount to “lots of parents taking councils to tribunal to get … normally very expensive independent schools”, a claim for which special needs experts have seen no evidence.

From his pulpit at the Department for Levelling Up, Michael Gove says that local authorities have understandable difficulty distinguishing between “deserving” families and “those with the loudest voices, or the deepest pockets, or the most persistent lawyers”. Lectures about sharp-elbowed parents from members of a cabinet in which 63% of ministers were privately educated demand a certain chutzpah, but there we are: what this really amounts to is the kind of twisted class politics that governments sometimes indulge in when they have run out of excuses.

Back in the real world, the local manifestations of a national educational catastrophe are all too clear. Just over two years ago, an independent report found that Suffolk’s services for kids with special educational needs (Sen) were so poor that the council was forced to apologise. The mess surrounding that verdict reflected disasters evident all over the country: the grinding local austerity that had caused the loss of two-thirds of the county’s Sure Start centres, and the fact that the coalition government had launched a hugely ambitious reform of the special needs system centred on the raising of its upper age threshold to 25, without providing councils with the money the changes required. Now, as more and more children and young people apparently reach crisis point, Suffolk is one of the scores of English councils whose spending on Send is constantly nudging it towards bankruptcy. To state the blindingly obvious, this is not about pushy mums and dads: it is a story about systemic failure, and its sheer expense.

On and on it goes. A mainstream education system increasingly focused on discipline and old-fashioned “attainment” has pushed vulnerable kids out (in Suffolk, the academic year 2021-22 saw more than 7,900 school suspensions – including, somewhat mind-bogglingly, more than 400 for children aged five and under ). Thanks to their absurdly low pay, there is a shortage of the teaching assistants without whom extra school support is simply impossible. In England, the number of children with special educational needs in mainstream schools fell by a quarter between 2012 and 2019, while the number attending special schools has increased by nearly a third in the past five years. Special schools, moreover, are now frequently oversubscribed, which sometimes forces children into schools so far from where they live that they have to endure impossibly long and expensive daily commutes.

A few weeks ago, Robert Colvile, the Sunday Times columnist and thinktank director who co-wrote the Tories’ 2019 manifesto, pinned a lot of councils’ financial woes on rising school transport costs and increased numbers of EHCPs. “There are, obviously, many children who genuinely need the help,” he said, with the implication that there are others who don’t. “But these plans are also the equivalent of a golden ticket. If you have one, the council is legally obliged to bend over backwards on your behalf, at the expense of everyone else.” I am the parent of a child with an EHCP, and I have had enough conversations with other families to know that councils very rarely bend over, backwards or otherwise, to deliver anything. As for the observation that help for kids with special needs is funded by the wider community, that sounds less like an indictment of a broken system than a basic civilisational principle.

The “golden ticket” trope references Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, threatening to recast kids who need help as spoilt brats. As Steven Wright’s case suggests, even if you manage to get your child an official promise of extra educational support, there is no guarantee that any of it will materialise. But there is now a drive to hack down even this hugely flawed means of holding the system to account. One of the government’s schemes for reining in special needs spending involves directing councils to cut the numbers of new EHCPs by 20%. At the top, there is talk of “more effective services” and “the right level of support”, but what any such moves are likely to result in is obvious: more kids stuck at home and families locked into despair, as politicians and their allies carry on blaming deep policy failures on – no, really – the parents of vulnerable and disabled children. There are no shortage of reasons for this wretched government to call it a day, but this may be the most damning of all.

• John Harris is a Guardian columnist