At this time when there is so much focus on national security issues and more integration with the mainland, two recent events have brought home the historic role of foreigners, good and bad, in the creation of the city.

First was that a half-Chinese Hongkonger with the very Irish name of Siobhan Haughey became the first to win two Olympic medals. That in itself was a lesson in how Hong Kong has to some extent avoided the ethno-nationalism that afflicts many places, the mainland included.

Second is the imminent publication of a biography of the late Hari Harilela, the Sindhi trader whose family came to Hong Kong in the 1930s and who went from small player in the tailoring business to richest Indian in the city with a string of hotels and other properties here and overseas. The biography written by formerly Hong Kong-based journalist and author Vaudine England includes much from Harilela’s own written recollections as well as a wealth of background information on Hong Kong’s business history and international links.

Much respected by other communities, the family-centric Harilelas are a latter-day reminder of the role of Indian merchants in the earliest times of modern Hong Kong. Indeed, even before the British had established themselves on the “barren rock” of Hong Kong, a Parsi trader from Mumbai, Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy (later Sir), had partnered with Jardine and Matheson in China trade.

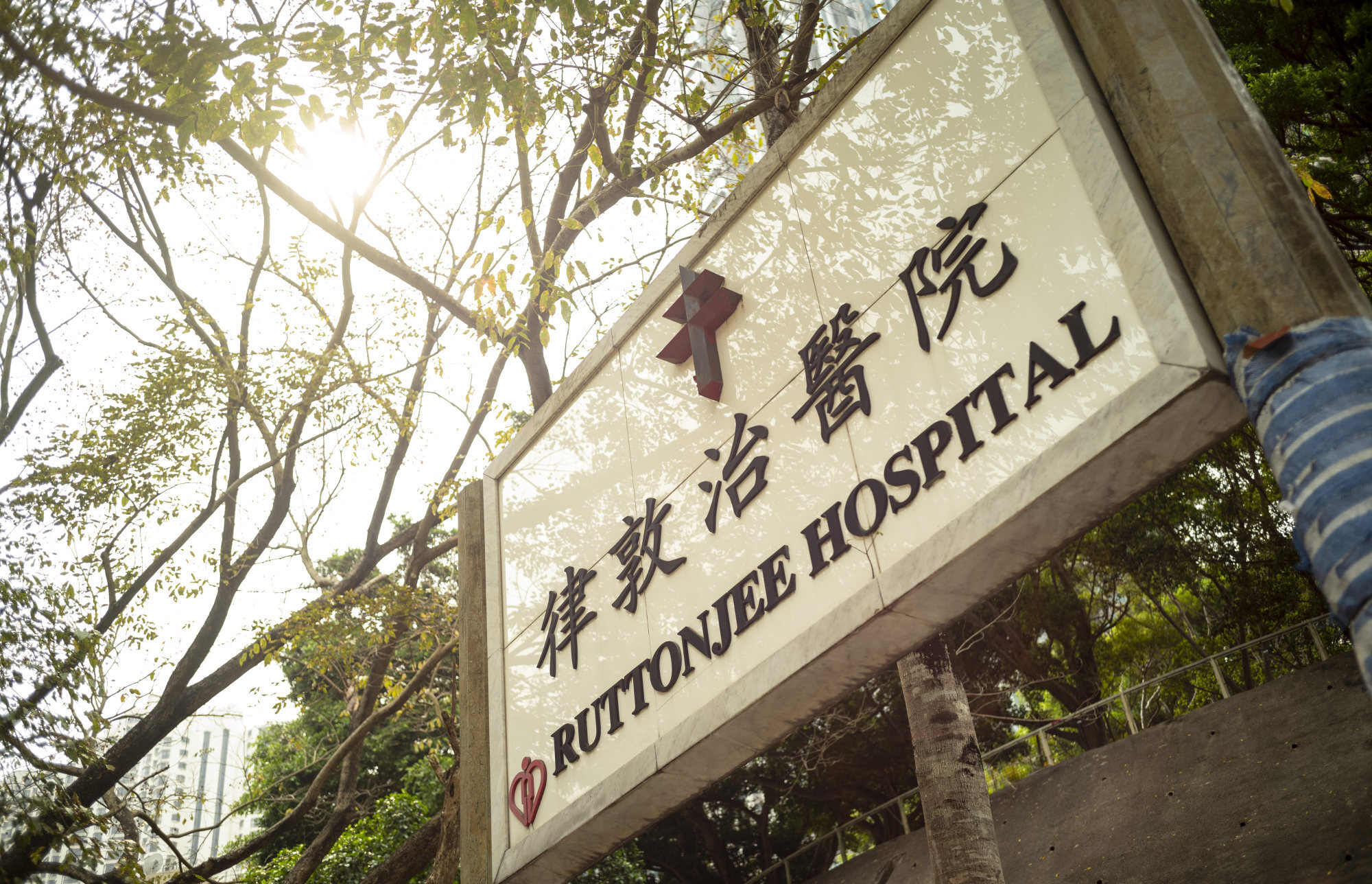

Other Parsi names from Mumbai are still with us, in Mody Road, named after Sir Hormusjee Mody, businessman and philanthropist who helped found the University of Hong Kong, and in Ruttonjee Hospital, founded by Jehangir Hormusjee Ruttonjee.

From Kolkata came Armenian businessman Paul Chater who was involved in multiple local projects and is commemorated in Chater Garden. Muslims from Gujarat also formed an important mercantile community.

Later it was to be the Sindhis who became both the most numerous and successful among the Indian community. Meanwhile, Jews from Baghdad and elsewhere, such as the Kadoories, made huge contributions, as did the Indian journalists who made Hong Kong a centre for English-language regional journalism from the 1960s to the 1990s.

My identity problem as a Westerner and a long-time Hong Kong resident

Of course all these migrations were all products of British imperialism, but there is no point in denying the obvious: that Hong Kong was a tiny place until the British, in need of a free trade port – not a colony for settlement – and good harbour on the south China coast acquired it from the first Anglo-Chinese war. China’s ports were elsewhere – cities such as Quanzhou, Guangzhou, Shantou and Xiamen.

Hong Kong, with its tiny population, had to attract migrants, an advantage to both the Chinese and foreigners who came.

It was Hong Kong’s special foreign circumstances post-1948 that allowed it to become a major textile exporter, and to transform into an international finance economy from the late 1970s.

Likewise, the dramatic growth of Shenzhen was driven by Deng Xiaoping’s foresight in drawing on Hong Kong’s proximity and service and trading expertise to turn the Pearl River Delta region into a manufacturing hub, from which evolved its hi-tech industries. Presenting the city now as an almost entirely Chinese enterprise is a xenophobic conceit.

Maybe history itself is passing Hong Kong by, with no British empire, possibly dwindling Western connections, frictions between China and its southeast Asian and Japanese neighbours, fewer links to overseas Chinese in Asia, a China itself turning inward. But the more the government emphasises integration with the mainland, the less space there is for non-ethnic Chinese.

Only a mainland-appointed provincial leader can revive Hong Kong

The large south Asian and Filipino communities have long faced discrimination, official as well as informal. The efforts of the Equal Opportunities Commission to counter it are worthy but unlikely to make much progress so long as the government itself makes no effort to involve non-Chinese in advisory and policymaking roles, or provide effective enforcement of the legal rights of Asians in domestic helper and unskilled worker roles.

Even the wildly excessive quarantine rules seem to reflect an inward attitude which should be alien to an international city.

It may not matter to those making big money or old colonial timers who blame Hong Kong problems on radical youth, if many feel a chill of fear as government listens intently to mainland voices seeking to limit debate and punish dissenting views. But it does matter that Hong Kong has in the recent past lost the presence of such writers and journalists as Ching Cheong, once a senior editor with Wen Wei Po and well-known commentator on local and Beijing affairs, and most recently, Steve Vines, English-language writer, broadcaster and entrepreneur whose 35 years in Hong Kong included presenting a regular RTHK programme. Both left out of fear for their freedom.

It does matter that the education sector is facing “reform” and artists and academics in sensitive fields are under pressure.

Liberal ideas and the rule of law are not for cherry-picking. You either have a system which is tolerant if sometimes messy, or you have one driven by an authoritarian ideology. You either have a system which revels in diversity, or you have another middling Chinese city like Quanzhou, once an international city glowingly described by travellers Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo.

The writing is on the schoolroom wall.

Philip Bowring is a Hong Kong-based journalist and commentator