She once vowed to re-orientate her nation’s foreign policy toward Moscow. She remains at odds with Nato and the European Union, and is viewed as an existential threat to both. But Marine Le Pen could take the helm of one of the world’s most powerful nations, a nuclear power and a permanent veto-wielding member of the United Nations Security Council, in just a matter of days.

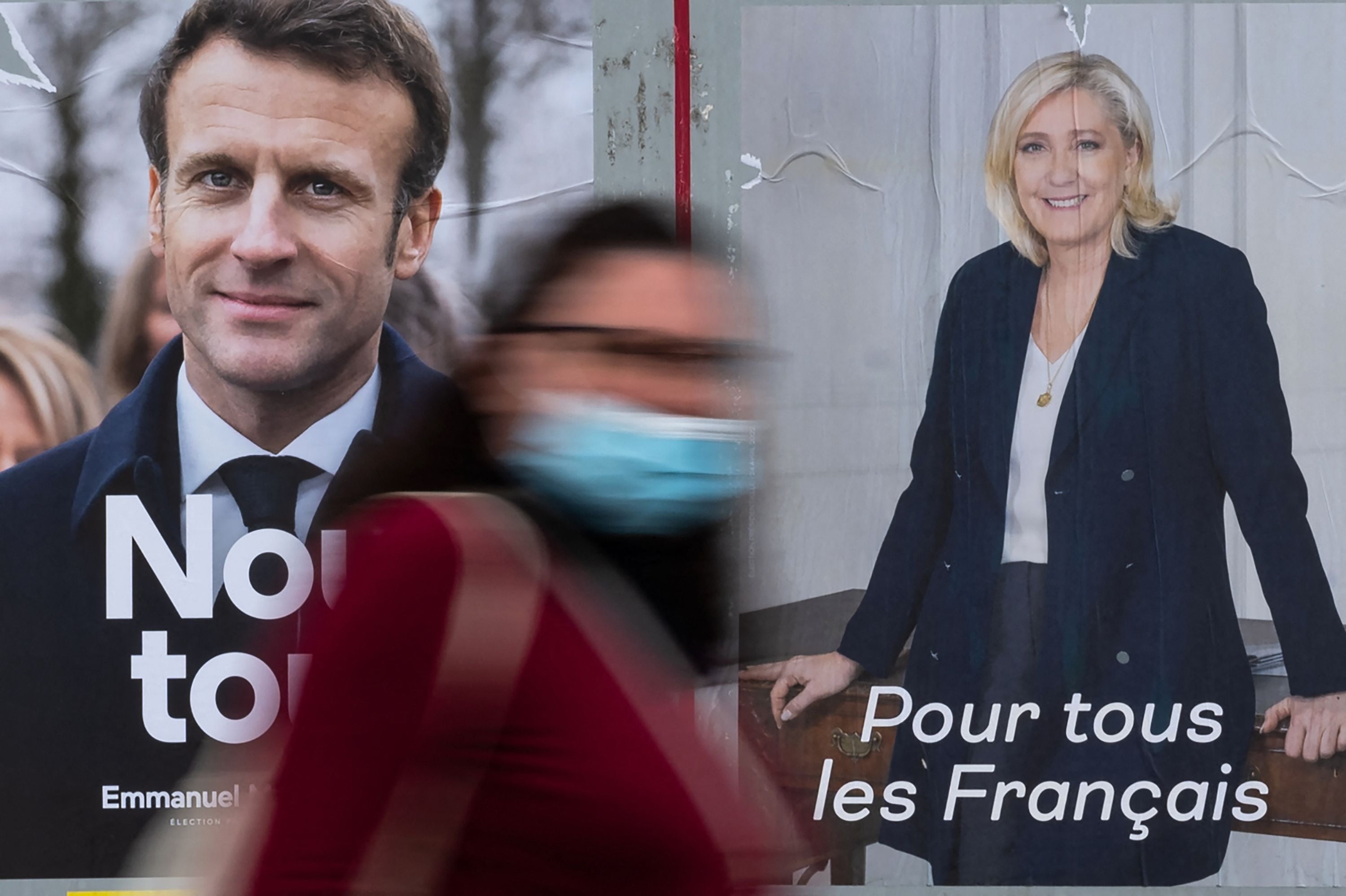

Though she has lagged in the latest polls, Ms Le Pen, the progeny of the far-right political dynasty of her father, Jean-Marie Le Pen, remains within striking distance of the French presidency in a closely watched run-off against incumbent president Emmanuel Macron.

The 24 April election comes at a singularly sensitive moment in European affairs with Russia pursuing an unprecedented land war against Ukraine and menacing the west with nuclear threats among others.

“It’s one of the few times when the whole world has a stake in an election other than the US presidential elections,” Judah Grunstein, editor of the World Politics Review, an international journal, said in an interview. “It’s one of the few presidential elections that is a global election. And the French electorate will have a huge impact on the world.”

According to the latest polls, Ms Le Pen has between 44 and 48 per cent of the vote but could score higher at a time when both anger at Mr Macron and apathy among those who despise both candidates is at a high.

The two also faced off five years ago in a second-round election that Mr Macron easily won. A highly anticipated televised debate is scheduled on Wednesday between the two candidates.

Ms Le Pen’s momentum has slowed in the days since coming second in the first round of elections. While Ms Le Pen has tried to focus the campaign on bread-and-butter issues such as inflation and wage stagnation, she has come under scrutiny for alleged misuse of European Union funds by her party, the National Rally, charges she insists were the result of politically motivated leaks, as well as her Kremlin ties.

Numerous press accounts have highlighted her previous support for Mr Putin, which included recognising Russia’s claim to Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula that it seized in 2014. Her comments in 2017 insisting Russia was no danger to Europe and that Nato was obsolete have come back to haunt her.

“Nato was created to fight the Soviet Union,” she said back then. “Today there is no Soviet Union. There’s Russia which doesn’t deserve to be treated with prejudice.”

After Mr Putin’s invasion, Ms Le Pen was forced to destroy thousands of copies of campaign material that featured photos of the two, and she modified her stance on Moscow to publicly condemn Russia’s unprovoked aggression.

But she insists on an eventual rapprochement between Russia and France once the Ukraine war is over. What’s more, she continues to advocate policies, including removing France from Nato command and defying the EU, that fit squarely into Moscow’s agenda.

One senior French official said that Ms Le Pen’s victory would damage the ongoing effort to defend Nato’s eastern flank as well as seriously threaten the EU. France currently has deployed ground forces to Romania and Estonia and is protecting skies over both the Baltic nations and Poland, crucial components of European security that would be hampered by a Le Pen victory.

“I think she is a Trojan horse,” said the official, speaking on condition of anonymity. “Russia holds her by all sides.”

It’s one of the few times when the whole world has a stake in an election other than the US presidential elections

This week, the magazine Nouvel Observateur published excerpts from a forthcoming book detailing the ties between Ms Le Pen’s inner circle and the Kremlin. They include long-standing personal and professional ties between members of her National Rally party, as well as millions of euros in loans from Kremlin-linked banks.

“The ties do run deep and they have been long in the making,” said Rosa Balfour, Brussels-based director of Carnegie Europe, a think tank. “It’s financial. It’s political. It’s ideological.”

Ms Le Pen’s support for Russia may actually be helping her at the polls among French voters long hostile to the power of the US. A submarine deal between Australia, the United Kingdom and the US, agreed last November, that scuttled what was considered a done deal between Canberra and Paris, rankled the French and resurfaced longstanding insecurities about the status of Paris within the western security hierarchy.

Mr Putin and the European populists such as Ms Le Pen also share similar hostility to immigrants, sexual minorities, and cosmopolitan values, with an emphasis on upholding Christianity and traditional family structures.

“The fact that Le Pen has not been tarnished with her association with Putin, is very indicative that the populist pro-Russian right is still popular and has traction,” said Ms Balfour.

Should Ms Le Pen win, the US, as the major force behind Nato, could reallocate resources to make up for any French withdrawal of forces.

But France, along with Germany, make up the core of the European Union, and though Ms Le Pen insists she does not advocate a Frexit, she has also said the matter could be put to a referendum. She has advocated defying EU rules and lowering French contributions to Brussels in what would amount to sabotage of the project.

“Her entire programme is incompatible with Europe as it exists,” said Mr Grunstein.

Ms Balfour predicted that France under Ms Le Pen would partner with Hungary’s Viktor Orban and other like-minded political parties in Italy and elsewhere to pursue nativist agendas that could undermine the entire EU.

“These countries could very easily form a blocking minority,” she said. “They could form some consensus around policies that could be destructive to the EU.”

Ms Le Pen and Mr Macron faced off five years ago in another perilous moment after Brexit and the election of Trump. Emboldened by those victories, Mr Putin did everything in his power to get her elected in 2017, launching a social media campaign and allegedly hacking into Mr Macron’s servers. But it failed spectacularly, with Ms Le Pen winning only a third of the vote.

In 2022, the Kremlin has done less, suggesting Moscow realised its ham-handed attempts five years ago to smear Mr Macron by leaking emails from his inner circle had backfired.

Instead, Mr Macron has done much of the work for him, proposing unpopular economic policies and alienating huge swathes of the electorate with what critics describe as haughty elitism.

“Sadly, [this time] it’s more self-inflicted,” said the senior French official, when asked whether Russia was trying to tip the scales in Ms Le Pen’s favour. “This time is different. People are angry at everything.”