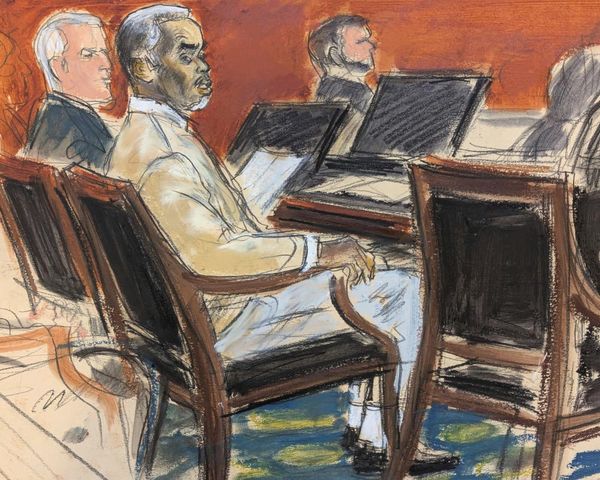

Simon Carter has teamed up with Thames & Hudson to showcase his 30 years of climbing photography in an all-encompassing photography book, The Art of Climbing, that is as much about the land as it is the action.

Carter's groundbreaking work has been shown globally for decades, cementing him as one of the pioneers of modern climbing photography. His imagery, as showcased in his new book, goes beyond that of the action sport and captures the essence of what climbing is: a physical connection to nature. His work captures the relationship between climber and landscape with great drama, but equally dignity and grace.

I found myself awestruck by the work and how each image was simultaneously an expertly composed landscape photograph and a sports / climbing photograph. I had to find out more about what it takes to be a climbing photographer and Carter's experience in the genre. Ahead of the release of The Art of Climbing, I sat down with him to learn more…

Which came first, photography or climbing?

I got into both photography and rock climbing as a teenager, but I have to say that it was photography that came first. When I was 15, I got really into it, and there were two aspects to this; I became fascinated with playing with black-and-white photography and developing film and printing.

I made a darkroom in my laundry room when I was 15 while learning photography at school. I then changed schools for the last two years of high school to a college in Canberra, Australia, which had a really good photography course so I pursued that.

At around the age of 17, I was also really keen on rock climbing. I was into both of them pretty heavily and they were always the sort of two constants in my life that have always been with me.

How were you able to combine your two passions?

It was a long process before I was able to combine those two passions into a career or a job. I was so keen on photography when I left school that my first job was at a local university in their photography department, thinking this was what I had to do to get into photography. I ended up spending probably 80% of my time in the darkroom, printing DNA gel snares and using close-up electron microscopes to help the scientists with their research.

I found that pretty demoralizing after two years. I thought that was the way into photography, but I just could not see myself progressing from that into being a photographer, so I became quite disillusioned.

During the second year of working there, I did a night school course in photography, and at the end of my first year, I had to hand in a portfolio of 12 photographs of anything. So I thought: rock climbing photographs! I hiked out to the local cliff with climbers and made all these montages to make it artistic, and I handed in my 12 photos – and failed.

I was really pissed off, because the ones that did well were these nudes on rocky beaches and contrived stuff in the studio, and I just thought, "That's nice" but there was no originality in it. They couldn't relate to what I did, so after two years I quit, and with a mate I went overseas on my first overseas climbing trip and my world opened up. I didn't photograph for years after that, I just gave it up and didn't touch a camera.

I started doing a bit more photography of rock climbing as I was getting more and more into it, just for fun. Eight years later, I became a full-time rock climber living in a tent by Mount Arapiles in Australia because that's all I wanted to do – I wanted to go climbing. Back then if you wanted to become a good climber, you just went climbing.

After becoming a full-time climber I started photographing my friends who are really good rock climbers doing spectacular stuff. There was no one else around to document what they were doing so I started photographing them. That's when I had my sort of "Aha!" moment.

When did you realize it would be a viable career path?

Well, at the time, there were no professional outdoor or specialist climbing photographers in Australia. There were only a couple of outdoor photographers and maybe a few in America making a living shooting and climbing. But I thought, I'm living in a tent – I've got nothing to lose.

I did a small business course and received a small grant from the government to help me get off [unemployment], which funds you for a year of living expenses while you start a new business. I started my business, spent a few months traveling around the country, and then published a calendar of rock climbing, the Australian Climbing Calendar 1995, and one thing led to another after that.

By publishing a calendar, I had enough money to keep going. After doing that for about four years, a publisher came to me and I made my first coffee table book on Australian rock climbing. That led to other things, including being invited to photograph overseas, which started my international travel and publishing a few more books.

My whole career is a series of one thing leading to another and something just coming along, and I have managed that now for 30 years.

You mentioned that were few rock climbing photographers at the time. How did you select your style, did you have inspirations from other photographers or were you shooting what felt right?

Both. There were some really good American climbing photographers at the time, like Bill Hatcher, Greg Epperson, and Jim Thornberg, and they were certainly inspiring, but I just followed my own path.

I think because one of my initial projects was photographing a calendar, I needed a single image that would be interesting to view, incorporating good climbing action, but I also wanted to show a sense of place, something about the climb, or the environment. So I was always thinking about what I could do with a single image that would speak for itself, that helped me find my style.

It became quite clear to me that every time I visited a place, I would ask myself the question of what is unique about this climb or this place, this area, the setting, or maybe, sometimes it was the climb that was interesting or unique. I'd ask myself, what is it? And once I'd identified that I'd work on a process of how to best capture it.

How did your personal experience in climbing aid your photography work?

It helped a lot. I'm grateful I spent all those years climbing before I started trying to get serious about climbing photography. The obvious practical aspect of having the technical skills, the climbing skills, the rope skills, the rigging skills to be able to get into position and work on a cliff safely and work with climbers. You've got to be able to understand things from their perspective if you're asking them to do things, you need to know what you're putting them through.

There's also the creative and motivational aspect because it's always been really important to me as a climber how climbing is portrayed. When I got into climbing photography there were concerns that climbing would be banned because people would say it’s dangerous. The only time climbing ever made the news was when there was an accident. I wanted to show the positive side as a kind of education to the public.

Touching back on the practical aspect, just being out on a cliff is often when you see the best angles or get the concepts for a shot. When I’d arrive at an area I'd climb for a few days and get to know the place, the layout, the light, and the access. It helps a lot in conceiving a shot and what might be possible.

I assume it also helped with gaining access to the climbing community if you're already a part of it.

That's right, yeah, because when I started I was just shooting my peers and they happened to be the best climbers in the country and when you're living with them in the tent next door, it's just mates going out and doing something cool. Now 30 years later, they can look at the book and go, "Wow, that was so cool!"

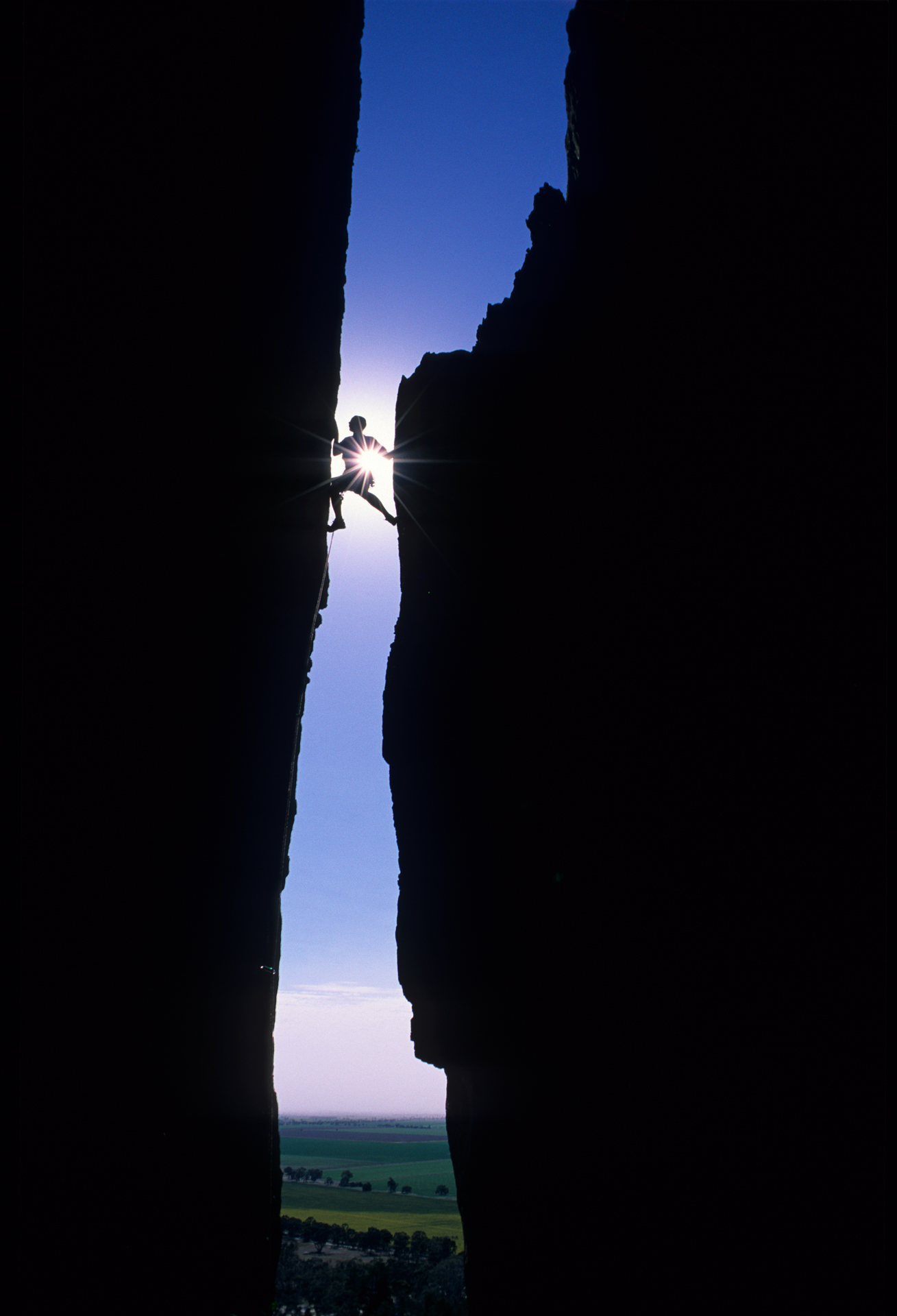

Your images capture both landscape and sport simultaneously. Was it a conscious thought to incorporate beautiful landscapes with sports, and how then did you blend the two?

Yeah, totally. Blending the landscape and the action has always been what it's about for me. I feel like just action shots alone can be impressive, but it misses something about climbing. I mean, you don't want pure action to be in every shot.

Then on the other hand, you've got your landscape, and then in between is a spectrum of how big the figure in the frame is and how important they are to the image. This is where I've always felt the challenge is.

For me, the perfect image has always been one that captures both perfectly – the landscape shot could stand alone as a landscape photograph but then if you've got genuine authentic climbing action, which you can quite clearly see, that to me is the perfect shot.

And as a viewer, it adds to that relationship between humanity and the landscape, which I assume is important to climbing?

Well, that is what it’s all about, for me at least. Climbing has grown and changed so much in the 40 years I've been climbing, and the 30 since I've been shooting it.

It's changed and grown so much, but personally, it's always been one of the great things about climbing. It allows you to connect with nature which becomes important. There are lots of different aspects of climbing, but that's always been an important one.

What's brilliant with a lot of these images is they show the scale of the land compared to us, almost as though showing how the power lies with the landscape.

Now that you mentioned the word scale, when we were looking at the themes chapters for the book we came up with one called Scale which was my concept, where all the shots showed a piece of rock and you just wouldn't know how big it was until you see the climber and then you understand the scale of what is going on.

How did you come up with the selection of chapter themes?

When we first decided to do the book and started looking at my entire body of work, we wanted to use the best work, but we were left wondering – how do we split that up? To me, the obvious answer was chronological; I thought "This is all about me, so let's set it out and show everyone my career." Then it's like, hang on, no, it's not about me, there's something much more interesting here, not just to climbers, but to anyone who might look at it.

This was quite an involved and long process with Thames & Hudson and they were great at pushing us forward with coming up with ideas. I didn't want it to be a destination thing so in the end, while working with the artistic theme, which we had from the title, we started looking at the artistry. I started developing chapters like Scale, Silhouettes, and Portraits, focused more on the climb and environment, but it just didn't quite gel.

To incorporate both the climbing and environment we decided upon features in the rock architecture, and that's how we ended up with the chapters on the lines, the walls, the overhangs, the arêtes et cetera.

It was cool because when I looked at my collection through that lens it was just like "Oh my god" it's obvious, and it’s so cool to see my work presented that way.

Would you say this is a photography book about climbing, a climbing book that has exceptional photography, or a combination of both?

It's a photography book about climbing. It's a photographer's take on climbing. It's not just about climbing, as if it had been a climbing book we would have done it by destination or style of climbing. Big walls, bouldering, aid climbing, or sport climbing – it would have been split up that way. But I think what we've done captures both and hopefully appeals to both interests.

What is the ratio of pre-composed / staged images to spontaneous captures?

My photographs are a mix. I've thought about this a lot over the years and I think it is like a spectrum. On one hand, you've got documentary photography where you get out there and do all you can to capture something or document what's going on, and if you can make it beautiful and artistic then even better.

Then on the other hand you've got more conceptual styles. Conceptual shots are ones where it comes about by asking the question. what's unique about this climb or this place? And when I ask that question and you find the answer it's about how you create the best image of that.

For example, I live here in the Blue Mountains and one of the unique features here is that, in the morning, the valleys fill with an inversion layer of cloud that sits in the valleys with a cliff above them. So there are opportunities to get a photograph with a climber on a cliff sitting above a sea of clouds, which is a cool concept, and it's unique to the Blue Mountains. So I asked myself, how could I get the best possible shot of a climber above an inversion layer?

The answer is quite hard, as there are very few cliff faces that catch the sun in the morning because everything faces west. So I spent years trying to find places where I could do this and then went through this process of rigging it and setting it up and having full pre-dawn starts to refine and capture the image.

So to me, the perfect conceptual image is where you come up with a concept and then find the best way to execute it.

The images in the book are beautifully composed. How is that possible when you’re hanging off a cliff face?

I should first mention that I take quite a lot of good climbing photographs from standing on the ground or a clifftop just by hiking. Maybe 30% of my shots were just taken with a difficult hike or a scramble from a defining vantage point.

But yeah, most of my shots are taken from abseiling so it’s mostly just rope work. The challenge is rigging your rope in the right location; once you've got the rope in place, you’re set. So you can either abseil down or use a or jumar to climb up. Then there are rope rigging techniques to stop you swinging, so it's just understanding rigging.

Has there ever been a case where you've set up, you've abseiled down, and realize you need to be 10 meters to the left?

Yes! It's a fun game going out on a climbing shoot. If it is under time pressure, if someone's climbing a route, then it is like "Oh no, quick!" But these are shoots where I must scout out a place and abseil down and check out the angles, look through the lens, and take a test shot.

I do my homework, but you often don't have that luxury, particularly when you're traveling. I might only get a few days or a week to try and capture some good images from one place.

Is it fast paced or does it require a lot of patience? When you've set up the shot, are you then having to wait for them to get into the right place?

It's absolutely both. It’s very much a hurry-up-and-wait sort of thing! You're waiting and then it suddenly all happens and it can often happen quite quickly. Sometimes you have the luxury of time and other times you inevitably end up under some pressure even while the shoot's happening, you've got to work fast.

You don't want to be holding the climbers up unnecessarily but you might want to suddenly be in a different position, so you're trying to think about the composition, what you're doing with the camera, your position, and the action. It's a fun game, so it is satisfying when you manage to get a good shot.

What are your favorite types of shots to shoot?

For me, my favorite shots tell something about the place as well as the climb. I love climbing and I love trying to capture the action, but part of the uniqueness of climbing is the location. That's what really inspires me. The places that climbing takes you to are spectacular.

What is your go-to photography kit and how has it evolved over the past 30 years?

The way photography has changed since I started shooting professionally 30 years ago is huge, it's a completely different game now. Back in the early days, when you shot climbing you'd have a roll of 36 exposures in your camera. I shot on Fuji Velvia rated at ISO 50, but I'd rate it at 36. Very slow film.

That had a strong influence on my climbing style and photography style in the early days, because you always need light on the subject. Whereas now when you can just crank the ISO to 800 and shoot in the shade or low light and capture really good action, back in the day shooting climbing action was hard in the shade.

I'm now shooting with the Nikon Z9, which can capture 20 frames a second easily. My recent purchase of the Z9 is the first time I've ever got a top-level professional Nikon. I've always gone a bit below, as they are usually smaller and lighter weight, but the autofocus is so good and it's probably the first time in my career I've got an auto that’s got a hope of tracking a climber.

I got my first digital in 2008 with the Nikon D3, because I finally realized that the resolution was excellent and better than what I could get from the scanned slide. But I was probably one of the last professional climbing photographers in the world to swap to digital. I held out because of the color palette issue.

Have you always shot with Nikon?

Always. I stood by them right through, even when they perhaps weren't the highest spec in some areas, but I'm super happy that I've stayed with them.

When shooting analog how were you able to meter on the side of a cliff?

I have a funny story about this: One day I was picking up film from the lab and the manager wanted to speak to me. He came in and he said, "How do you do it?" He wanted to know how I could shoot a whole roll of film and every exposure was perfect. Getting your exposure on film was not easy, especially when the light changes.

So what I did is I developed this technique based on the zone system and I would use a spot metering mode in the camera and I'd point it around the different parts of the scene and I'd become quite familiar with judging in tones in rock.

So I'd look at a bit of bright orange rock and go, "Oh, it probably needs to be about two thirds of a stop overexposed." And so I'd use spot metering mode, dial it in and point it around the scene to make sure that exposure made sense when I wanted it to darken, and that's how I did it. That was one of my most unsung achievements that I'm personally most proud of.

I’m sure this book will inspire many who view it. What is your advice for someone wanting to get started in climbing photography?

The main issue is safety. It should be quite obvious working on cliffs, but because of that, I would highly recommend that anyone wanting to get into it, spends quite a few years just climbing and becoming experienced at climbing before they try and work photography into the mix. Once you start working on a cliff and dealing with cameras it's quite distracting, so you need to know what you're doing so you can rig your ropes safely.

Being capable as a climber is going to be essential for capturing a lot of these images. You can take some shots from the ground, but ultimately you need some sort of climbing skills to be able to get around in these locations and work safely and efficiently. So that's my main advice.

New photographers are using the latest technologies such as drones and strobes and the way technology is changing now is very fascinating, but for me, it's not been about being up with the latest technology. I think as a photographer it's quite easy to get caught up in following trends because the technology allows you to. What's important, and this became apparent to me when I was working in the darkroom all those years ago, is it's about having a vision.

Working in the darkroom taught me that I didn't want to be a photographer at all costs. I didn't want photography to be a job. It wasn't about being able to just say, "Hey, I'm a photographer, I make a living taking photographs." I feel that when I see some people on social media, it's like, why are you doing this? Is it because you want recognition as a photographer? What is your vision?

If I was going to do it, I was going to be on my terms because I was inspired by something and because it had some meaning to it. I was never going to allow it to be just for a job.

The Art of Climbing by Simon Carter is an incredible look at a genre of photography that doesn't often reach the mainstream spotlight. It is not only packed full of spectacular images, but holds a wealth of information on climbing, the landscape and the photographic equipment used to capture the images.

Accompanying texts from some of the world's leading climbers add incredible depth to the book and provide another dimension of context to the imagery. I have had this book for a little while now and it has kept drawing me in for another look, and each time I see or learn something new. It is certainly a fantastic coffee table book!

Published by Thames & Hudson, The Art of Climbing by Simon Carter will be available from May 28 in the US, and is on sale now in the UK and Australia. The price is $45 / £30 / AU$59.99.

You may also be interested in our guides to the best coffee table books, the best books on photography, and the best books on portrait photography.