One of the primary roles of arts and culture is to hold a mirror up to society. The stories artists tell through books, performance, movies, music and visual art reflects an image of who we are, and shows us who we might yet become.

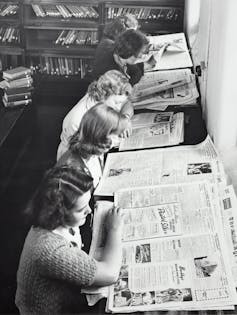

Journalism plays a crucial role in holding a mirror to this mirror. Investigations, interviews and reviews reflect and amplify the creativity and conversations explored by our artists.

But despite some bright spots of high-quality coverage, arts stories are often deprioritised in general media. Only 13% of Aotearoa New Zealand’s total media coverage focuses on arts and culture, and only 3.25% on art forms outside film, music and TV.

My new research report, New Mirrors, written with Rosabel Tan and commissioned by Creative New Zealand, investigates the state of contemporary arts journalism and proposes two pathways to strengthening this sector: a dedicated fund for arts and culture media projects, and an Arts Media Centre to connect media and creative sectors.

A dusty mirror

There is little dedicated arts space in the general media. Stuff, New Zealand Media and Entertainment (NZME) and the Otago Daily Times increasingly place arts content behind paywalls. Specialist platforms often have to compete in the same funding rounds as the artists they cover.

To better understand these challenges, we spoke with 52 artists, arts organisations, publicists, editors, journalists and decision makers across the arts and media sectors.

We heard arts media is under critical pressure, and significant challenges limit its growth: stretched budgets, reduced staff, production pressures and low pay. Freelance journalist Tulia Thompson spoke about being paid NZ$250 to write a 1,200-word review of three books, “which makes it more like a hobby”.

But we found a huge appetite to strengthen coverage. Connie Buchanan, deputy editor at E-Tangata, said the ideal was to be able to offer “decent, informed criticism of the arts landscape”.

Our research confirmed the need for a stronger and more visible representation of our arts and culture sector in our media, better reflecting the stories of Aotearoa New Zealand.

There is a significant audience for arts and culture: 96% of adults in Aotearoa New Zealand participated in arts and cultural events in the past three years.

As we argue in the report, strengthening arts and culture media leads to better public conversations, more engaged arts consumers, and a healthier arts and culture sector.

Coverage builds an audience, but it also supports future career opportunities for artists and ensures work is remembered.

Artist Bridget Reweti spoke about the importance of “high-quality writing” to support institutions and curators to understand the value of an artwork, and how mainstream media coverage “feeds into broader knowledge and people knowing that this work exists”.

As Mihi Blake, cofounder of communications agency Māia, told us:

There are so many stories, and people want to read them; people want to have their lives enriched by arts and culture and music. That is the richness of being alive.

Read more: Life after redundancy: what happens next for journalists when they leave newsrooms

Under-resourced and under strain

New Zealand’s media sector has experienced considerable volatility over the past two decades.

Between 2006 and 2018, the number of journalists working in Aotearoa New Zealand more than halved. New Zealand’s media sector is currently facing formidable headwinds due to the closing of the government’s contestable public-interest journalism fund, declining readership numbers, and a steep drop in advertising revenue,

Arts coverage, says David Rowe, head of journalism planning at New Zealand Media and Entertainment, “tends to suffer first, because in terms of core business, it’s not right at the absolute heart”.

It’s been 16 long years since Frontseat, TVNZ’s last dedicated arts show, broadcast its final episode. Today, opportunities for coverage of arts stories on television and commercial radio are rare.

While The Post expanded its daily arts and culture coverage this year in response to audience demand, many major newspapers in Aotearoa New Zealand have dropped specialist arts positions.

Former Stuff journalist Charlie Gates painted a stark picture for us:

When I started at The Press, in 2007, there was an arts editor, two film reviewers, two or three cultural writers, a feature writer who specialised in culture and things, and that’s all gone now. That’s all completely gone.

A path forward

We’re facing a national deficit in arts and culture coverage. This has impacts on social cohesion, wellbeing, and our sense of who we are as a nation.

We propose two key investment pathways to address this deficit.

1. Create a public fund for arts and culture media projects

The current funding models aren’t working. We need a dedicated fund that invests in arts and culture media projects, with co-investment across multiple agencies like Manatū Taonga, Creative New Zealand, NZ On Air and Te Māngai Pāho.

By pooling resources and ringfencing funding, we could enable both specialist art platforms and general media to grow coverage, shining a spotlight on more artist voices, building capacity in the regions, and recognising arts and culture coverage as a public good.

2. Create an Arts Media Centre

An independent body that connects our media and creative sectors could enable high-quality arts and culture journalism through training, advocacy and relationship-building.

Aotearoa New Zealand’s Science Media Centre, funded by the ministry of business, innovation and employment, offers a possible model. Since its launch in 2008, it has played a pivotal role in strengthening the quality, accuracy and depth of science reporting.

These two interventions hold the potential to have an enduring and positive effect, creating the infrastructure needed to support the long-term sustainability of our arts media ecology and for our creatives’ views and voices to be heard more often.

With new mirrors, media can better reflect the central relevance that arts, creativity and storytelling plays in the lives of New Zealanders.

James Wenley received funding from Creative New Zealand to conduct this research.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.