The world is falling miserably short of reducing carbon emissions in line with the Paris Agreement, a 2015 treaty to keep global warming well below 2℃.

The results of this failure are a greater increase in the prevalence and severity of extreme weather events, more rapid sea-level rises and an elevated risk of triggering irreversible climate tipping points, like the collapse of the West Antarctic ice sheet or the loss of the Amazon rainforest.

The speed and magnitude of these changes have immediate consequences for ecosystem health and biodiversity. Further, sustained climate change threatens fundamental dimensions of human wellbeing.

There are also frequent claims about looming “climate wars”. These depict a chaotic world with unsustainable mass migrations, devastating weather-related disasters and violent clashes for survival in an era of rapidly diminishing resources.

However, the link between climate change and conflict is weak when compared to the main drivers of conflict, notably poverty, inequality and weak governance.

Instead, violent conflict in the context of a warming planet plays another and far more prominent role: it’s a critical driver of vulnerability, which makes adverse impacts from weather extremes more likely and more severe. In other words, violent conflict weakens communities and countries so that they are not in a position to adapt to the changing world around them.

Although it may be possible to maintain peace without successful climate adaptation, successful climate adaptation is impossible in the absence of peace.

How climate change affects conflict

Climate change is commonly framed as a risk multiplier that worsens conditions known to increase conflict risk, such as poverty and inequality.

Research shows that adverse climate conditions may lead to more support for violence. These conditions can also contribute to escalating or prolonging conflict. This is particularly the case in places marked by climate-sensitive economic activities, political marginalisation and a history of violence.

Typical hotspots of such dynamics are found in the Sahel and rural East Africa. However, the true role of climate change in causing conflict in these settings remains disputed. How climate shapes peace and security depends on how societies respond to climate change.

In a recent journal article, my colleague and I outline several potential ways climate policy can be linked to drivers of conflict. These could, for example, be by way of addressing energy insecurity, financial vulnerabilities from altered tourism patterns or loss of oil revenues, and land-use competition related to environmental conservation projects.

These links have attracted little systematic study to date and remain a key priority for future research.

How conflict affects climate risk

The link from climate to conflict seems to be modest. But the reverse – from conflict to climate vulnerability – is very strong.

Armed conflict ruins economic activity and livelihoods. It threatens food security, obstructs markets and public goods provision, damages critical infrastructure and triggers forced displacement. All of these erode local capacity to cope and adapt to environmental hazards.

Put simply, armed conflict is development in reverse. The consequence of the war in Ukraine on the food crisis in developing countries today is evidence that armed conflict can affect social vulnerability and human security at a global scale.

Given the devastating effect of conflict on coping capacity, it’s extremely worrying that violent conflict is on the rise in Africa. The continent is already judged to be the most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

Conflict, alongside the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, has also been identified as a major cause of recent reversals in sustainable development. The most severe humanitarian crises today are all found in countries suffering from major conflicts and wars.

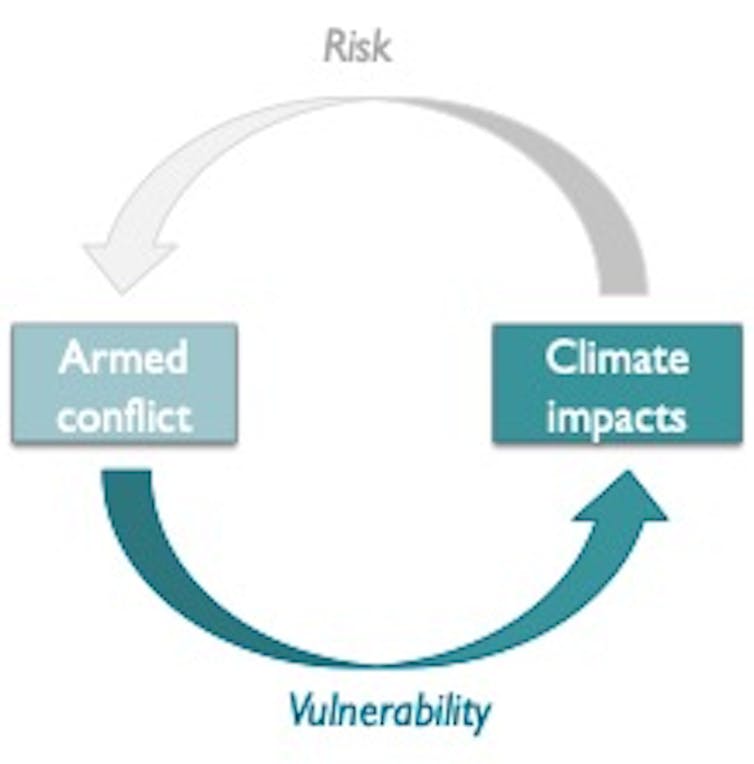

A vicious circle

Each of the processes outlined above challenges sustainable development:

violent conflict deters long-term growth and ruins local capacity to manage climate-driven risks

climate impacts threaten human security in vulnerable societies, thereby increasing conflict risk.

Together, they may result in a vicious circle of destructive effects.

The solution is peace

The ways in which climate change and extreme weather events challenge peace and security are widely acknowledged and increasingly well understood. This is why the likes of the UN’s Climate Security Mechanism exist. The UN Development Programme also plans to “climate proof” peace-keeping and stability in regions that have experienced conflict.

Climate security has additionally been the subject of nine open debates at the UN Security Council since 2007, seven of which have been held in the past four years.

Successful climate adaptation allows for sustainable development and has important benefits for peace. However, it should not replace traditional conflict resolution and peacebuilding programmes. And it is important to be aware of the dark sides of environmental peacebuilding.

Less attention has been paid to “conflict proofing” climate adaptation programming. Instead, adaptation plans often assume peaceful settings and fail to consider political contexts that may underpin local conflicts and be a major source of vulnerability.

Yet, without peace on the ground, actions to address climate risks will be restrained, ineffective and possibly counterproductive.

From this follows a key insight: in violent contexts, peacebuilding should be seen as the first and most crucial step toward addressing complex climate risks.

Resolving conflict is no replacement for effective climate adaptation. But climate action without a safe environment with functioning governance structures is unlikely to solve structural sources of vulnerability. As has been said elsewhere: no peace, no sustainable development.

Halvard Buhaug receives funding from the European Research Council (grant no. 101055133).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.