There are 400,000 fewer children in poverty than there were in 2010. We are taking steps to alleviate poverty, the gap between rich and poor has actually diminished.

Boris Johnson, prime minister and Conservative Party leader, on the BBC Andrew Marr show on December 1

Boris Johnson’s bold claim about child poverty needs some careful consideration – it is a very partial truth that completely misrepresents wider realities.

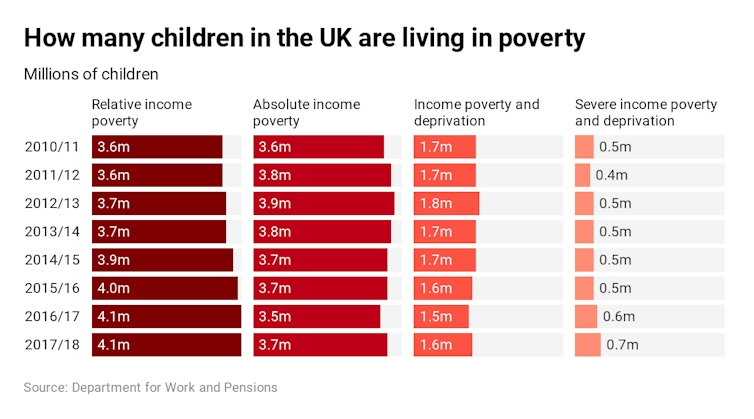

Let’s give credit where credit is due. Johnson did not explain how he reached the figure of 400,000, and the Conservative press office did not respond to a request from The Conversation for his source. However, it’s likely that he was referring to the absolute low income measure of child poverty, which did fall from 3.9 million in 2012-13 to 3.5 million in 2016-17. If so, his claim is accurate – but only if it refers to this time period.

If Johnson was using the absolute measure of child poverty, then his claim is out of date. Half of this “progress” disappeared in a single year, as the level of child poverty using this absolute low income measure has since increased by 200,000 from 2016-17 to 2017-18 – from 3.5 million to 3.7 million.

The so-called absolute measure of child poverty compares contemporary income against income in 2010-11, adjusted for inflation. This is a measure of whether the poorest families are seeing their incomes rise in real terms, and in the figure above, takes in families earning below 60% of median income, after housing costs. However, if everyone else’s income rises faster than the poorest families (which it has since 2010-11), then even with this increased income, it becomes ever more difficult for these families to buy what everyone else can afford.

So there are serious shortcomings with using such data to tell a good news story about child poverty in the UK.

Other measures tell other stories

Five points are worth considering. First, and most importantly, the absolute low income measure of child poverty is one of a group of inter-related indicators that should be looked at collectively if we are to completely understand child poverty.

The other two official measures of child poverty published by the Department for Work and Pensions tell a different story. The number of children living in poverty is estimated to have increased between 2010-11 and 2017-18 by 500,000 under the relative low income measure. This focuses on the here and now. It answers the question: “This year, how many of our children are living in a household whose income is so far below a typical income that we know that they are unable to afford to buy what we reasonably expect a household to be able to afford?”

Although the relative low income measure alone also presents a partial understanding of child poverty, it is this measure that is most widely used by experts to describe current levels of child poverty. And, it does not make for good news for the UK.

Matters are complicated further when we look at trends for the third measure – low income and deprivation combined. This measure suggests that the number of children living in poverty has fallen slightly since 2010-11 (by 100,000). But within the group who are living in poverty, the number living with severe low income and material deprivation – measured as below 50% of median household income for that year – has increased by 200,000. Put simply, the poverty of the UK’s poorest families has intensified in recent years.

Second, other organisations that measure child poverty, such as the Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS), the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and the Social Metrics Commission all advise that child poverty has worsened. Johnson’s claim is not supported by expert opinion.

Third, Johnson’s claim of progress flies in the face of common sense under the UK’s economic model. Child poverty increases if the government reduces the value of benefits with a benefit freeze. It increases if the cost of living goes up as a result of the loss of local services that can no longer be sustained by local government. And it increases if working families cannot earn enough income through the paid work that is available to them. Decreasing worklessness will not result in less poverty if it is replaced by low earnings and precarious work.

Fourth, if so inclined, it is just about possible to spin a good news story about child poverty by misusing the available evidence. However, as the IFS pointed out in 2017, child poverty is set to increase in the years ahead.

Finally, it really is a cause for concern if the prime minister is minded to celebrate the “achievement” of reducing the number of children living in poverty to 3.5 million.

We should not forget that rising child poverty is not inevitable. It is not determined by the economy. It is a result of the political choices that are made within the prevailing economic conditions. These political decisions have inflicted great harm upon many children in the UK in recent years, and more great harm will be inflicted upon many more children if the UK government does not change its approach.

Verdict

Johnson did not lie about child poverty. However, he pedalled a dangerous truth in his interview with Marr, a misleading account that implied that child poverty was becoming less of a problem in the UK. It is not. Children in poverty need the next government to acknowledge the scale of the problem and to acknowledge that, for the majority of children living in poverty in the UK, their parents earnings from work is not enough to lift them out of poverty.

Checking the Facts is a series by The Conversation in which experts review claims made on the 2019 general election campaign trail. If you have any claims for an expert to check, you can: email checkingthefacts@theconversation.com or tweet us @ConversationUK with #checkingthefacts or DM us on Instagram @theconversationdotcom

This article was updated on 6 December to make the time period of the 400,000 drop clearer.

John H McKendrick receives funding from the Scottish Government to support the work of local authorities who are working toward meeting their obligations under the Child Poverty (Scotland) Act.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.