A forest is more than an outdoor space filled with trees: it is a model for how we can live our lives and create architecture for the future. Growing up in northern Japan, I spent my childhood days playing in the forest. It was a place of intimacy, with many diverse areas yet nothing divided, everything softly interconnected. As we move into 2025, I see the forest as a model for architecture and society. It shows us how distinct identities can thrive in diversity while still being connected – and how harmony between humans and nature can be rediscovered.

Today feels like the dawn of a new modern age. It is a time of profound change – and change always sparks new ideas, concepts, designs. Our values are shifting, societies are evolving and this moment in history feels similar to the start of the 20th-century modern age, when new ideas deeply shaped how we went on to live and think.

Sou Fujimoto on 2024 and what's coming in 2025

Now, after more than 100 years, many “modern” mindsets and “modern” concepts are irrelevant. The COVID pandemic made us realise how outdated much of it is. We now have new situations, points of view and questions to answer: about sustainability, diversity, biotechnology, AI, over-connection and nature. The year ahead is likely to be an exciting time, particularly for younger generations thinking about the world around them. I see creative revolutions across every category – architecture, art, music. My hope is that the young designers of tomorrow will be brave and honest enough to continue driving this change forward.

For me, 2025 is all about the Osaka Expo, which opens in April. I have been working intensively on this for the past five years, creating a large timber ring structure. It’s a truly global event, a wonderful integration of different pavilion designs and international activities. Many countries – including Japan – are trying to explore future architecture based on sustainability. There are many wooden structures and I sense a real push across the world to create more sustainable architecture. I’ve noticed, from monthly visits to my Paris office, that in the last 10 years, there has been a strong global shift towards wooden construction, natural materials or reusing and recycling. This has become even more active since the pandemic.

Now, the Osaka Expo sets the stage for realising the newest and most innovative trials into wooden construction. One can wonder: ‘What does sustainability look like in the current climate?’ As a Japanese architect, it’s interesting for me to think about this, because Japan is quite far behind globally in terms of sustainability. The Expo is a great opportunity for Japanese society to think more deeply about sustainability in a global context. When we revealed our proposal, many Japanese didn’t understand the wooden ring we designed for the Expo.

For many, wooden construction is for private homes, temples or shrines – it’s not thought of as a showcase for the latest building technology. But recently, the ring has been widely published at the same time as other large-scale wooden constructions are also being noticed – and I feel that Japanese people are starting to understand our vision. It's all about opening people’s minds to the different possibilities of wooden construction – and hopefully, this will be emphasised through other structures such as the Italian Pavilion and Czech Pavilion.

In many ways, Japan is behind global standards. But we have good quality of design and architecture; plus, society is very well organised. We also have a tradition of living together with nature, an important aspect of Japanese life. We need to push this to the world, as for more than 1,000 years, we have been living with nature in Japan. Daily life and philosophies have evolved in harmony with nature. We see this in the traditional Japanese house, with its sliding paper walls and blurred boundaries. The architecture itself is very light: the garden and surrounding nature are the main focal points of a home. The built structure is part of a wider living environment and nature. So how can we integrate nature further into design? It’s not just about bringing greenery onto buildings – this is always nice, but it goes beyond that.

The important point about nature is that we cannot control it. In the 20th century, humanity set out to control everything – we learned this wasn’t possible. Earth is bigger than us. It has dynamism, power, diversity of animals and plants, and beautiful ecosystems. This moment in human history is an opportunity to open our minds – and sometimes be exposed to the uncontrollable. This is not a negative state because the uncontrollable is unpredictable, bringing inspirational surprises. Of course, sometimes we need to control nature, but we have to find a better balance between enjoying it, embracing its surprising aspects and living in harmony with it.

The pandemic is the perfect example. Until the last century, we developed and built a very efficient system for society – this was important but maybe too controlling. It had a hugely negative impact on nature, Earth – and humankind. We can see this in our buildings. We have tried to make buildings as functional as possible – but if you make them too functional, it limits people’s minds and ultimately their lives. Human life is like nature: it is flexible and ambiguous. If humans try too hard to control everything, they create negative pressure – we need space for freedom.

Having spent a lot of time in Paris, I admire European countries – there, society is based on the idea of individual freedom. In Japan of course we have this – but the idea of harmony in society is also very important, so people often repress their personal freedom and follow societal consensus. This can be both positive and negative.

Japan is becoming more diverse – but the economy is not in a good state and Japanese society unfortunately tends to become more conservative when this happens. Having said that, there are still many visionary individuals – many of my clients, for example, are founders of companies trying to do something different and more suitable for the future and the Earth. I am interested in how we can combine the ideas of “diversity” and “unity”. We need to enhance diversity – but avoid people being divided and clustered against one another. We should help create a sense of unity, with interactive relationships between different points of view and attitudes.

This is discussed in the masterplan at the Osaka Expo. This is extremely important in light of a very divided and complex global situation. As humans, we need to be generous – and accept different values and viewpoints and the fact that people are uncontrollable, just like nature. Otherwise, we will never finish fighting one another. The first quarter of this century has witnessed huge revolutionary changes – not just physical, in the form of wonderful design products, but also conceptual. Now, people understand the importance of public spaces – places for gathering. We need to slow down.

One way to explore this dynamic is through materials. Over the next 50 years, biotechnology – which hovers somewhere between nature and artefacts – will become increasingly important in architecture. Architectural revolutions have always gone hand-in-hand with materials. Modern architecture was established on steel, concrete and large-sized glass. Now, wooden construction is coming back. This marks the start of a new phase. And biotechnology will be next. Can we use materials that have healing qualities, and that can self-renew?

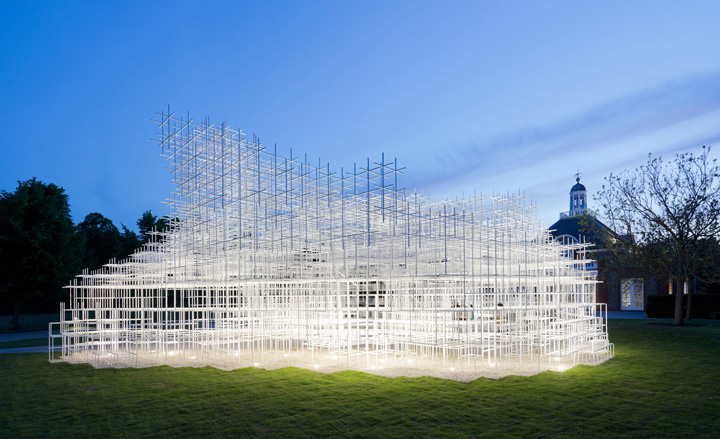

The idea of localised design is also becoming more important. Since last year, I’ve been on the advisory board for the Serpentine Pavilion’s selection of architects. Their global research into what is happening around the world is fascinating. It is exciting to see so many architectural trials underway, based on different cultures, traditional materials and climate situations. Younger generations seem proud of their countries and cultures and are increasingly trying to develop unique answers for the future. It's localised but universal.

One region that many will be watching in 2025 – not only for its political developments but in terms of creative growth – is the Middle East. We have several projects underway in Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi. The region seems to be passionately active in developing architecture and design, with many global architects involved. No one knows how this will unfold, but it’s an exciting time, it feels like a place where the boundaries are being pushed in unexpected directions.

I’m curious and optimistic about changes brought by AI technology in the creative industries. In our studio, AI makes us look at what we are doing – it’s like a reflective mirror, generating drawings and images which pose the question to ourselves: ‘Is this Fujimoto?’ We understand this may or may not be part of our creations – what is most important is the discussion it activates. It’s through conversations that I find new ideas or new meanings to existing ideas. I feel this technology can stimulate creativity. However, many ideas originate from the human form. This physical body experience reflects our thinking and philosophies. For now, AI doesn’t have a body – so I am curious, if they obtain knowledge and data about the body, can they think about it like humans? Either way, I am optimistic – because if different ideas and perspectives emerge, this can be inspiring and interesting for us.

Finally, how does one connect all these ideas, thoughts and places together? For me, it comes back to the forest. This idea of a conceptual forest can be an architectural model for the future. It is timely and timeless – and as the world continues to change and surprise us, I hope that younger generations can understand the beauty of trying to create a world where there is harmony between diversity and unity, humans and nature – just like a forest.