Wayne Tunnicliffe, head of Australian art at the Art Gallery of NSW, has a sense of humour. The main entrance to this year’s Archibald, Wynne and Sulman Prize exhibition features a giant black and white photograph of a student demonstration from 1953. At the time the gallery trustees, who are named in Archibald’s will as the judges of the prize, were actively hostile to any idea of modern art. Their taste was so predicable that the gallery’s director, Hal Missingham, would write the telegram congratulating the winner before the voting.

By the 1970s, when I was working at the gallery, trustees were less likely to vote for their mates. But there was a deep cultural disconnect between the aesthetic taste of the gallery’s professional curators, the arts community and the media, who lived in hope of a controversy such as the 1944 William Dobell court case.

The task of turning the trustees’ choice into an interesting exhibition was best described as “a challenge”.

In recent years, the gallery’s board has learned to have more faith in the two artist trustees, and winners have tended to reflect their interests. It is therefore appropriate to thank both Tony Albert and Caroline Rothwell, who also judged last year’s prize, for this year’s very lively exhibition. The awarding of the prize to Julia Gutman’s embroidered and painted collage last year appears to have unleashed an especially lively range of entries this year.

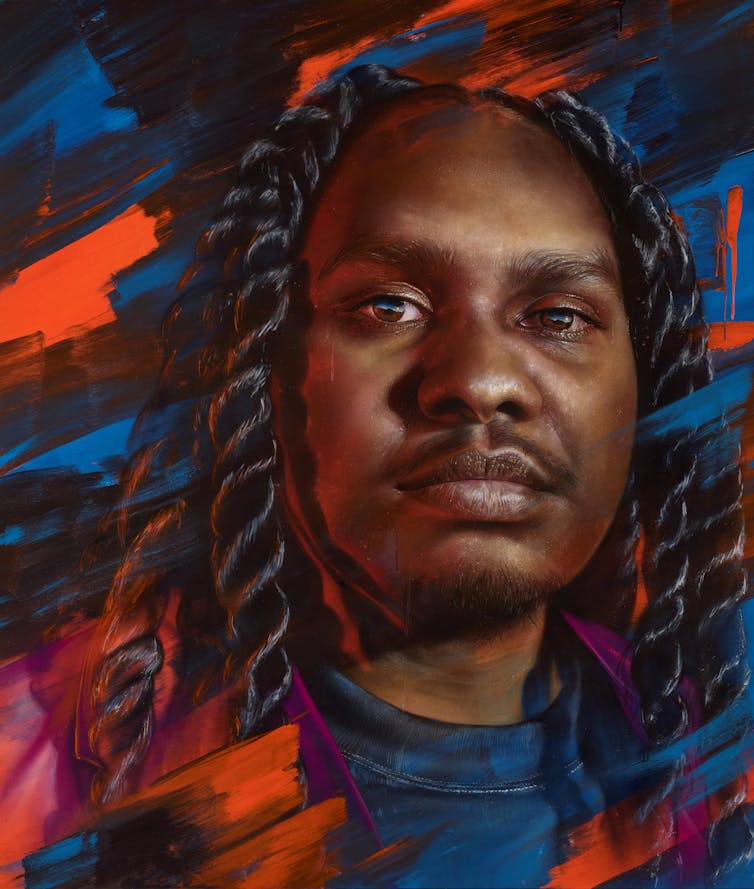

In addition, the Packing Room prize is now judged by a trio of the gallery’s expert installation crew, all of whom know more about art than just what they like. This year’s prize winner, Matt Adnate, began as a street artist spraying graffiti. He is now better known for his murals, including some of the popular Yolngu rapper Baker Boy – the subject of his winning painting.

The biggest change is that the exhibition has been hung by the Head of Australian Art, an indication the gallery now takes the Archibald very seriously indeed. Only a very brave person would predict this year’s winner of the Archibald Prize.

Whether or not they are likely to win, there are quite a few works that deserve a closer look. Some because they are wittily original, others because of the political message they carry, or because their subject is especially newsworthy. Then there are paintings that simply bring joy.

There is a special pleasure in looking at Emily Crockford’s Singing with my selfie at the top of the world with my imagination, remembering her previous exhibits and seeing how her art has developed. That is also true of Digby Webster, another returned exhibitor who has painted his filmmaker, Trevor. Meagan Pelham, who like Crockford works through Studio A, has called her portrait of the National Portrait Gallery’s curator, Isobel Parker Philip, Highlight in the moonlight.

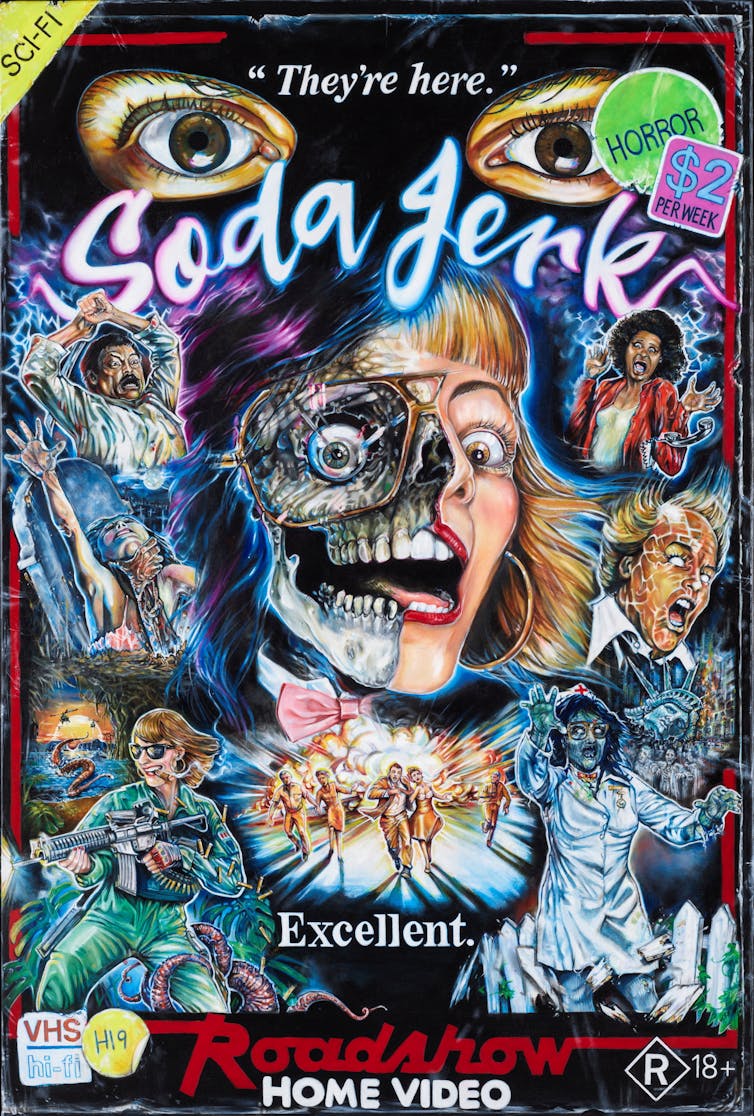

Drew Bickford’s gloriously lurid Direct-to-Video portrait of filmmaking duo Soda Jerk is at first a puzzle as the two sisters have been melded into one, but he has captured both their ambiguity and their glorious sense of anarchy as they happily make “directors’ cuts” of iconic cinema.

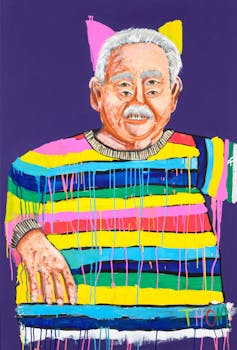

Camellia Morris’s Wild Wild Wiggle is just fun, while Thom Roberts’ Big Bamm-Bamm is a reminder of a time when anything relating to Ken Done (the sitter) would automatically be rejected.

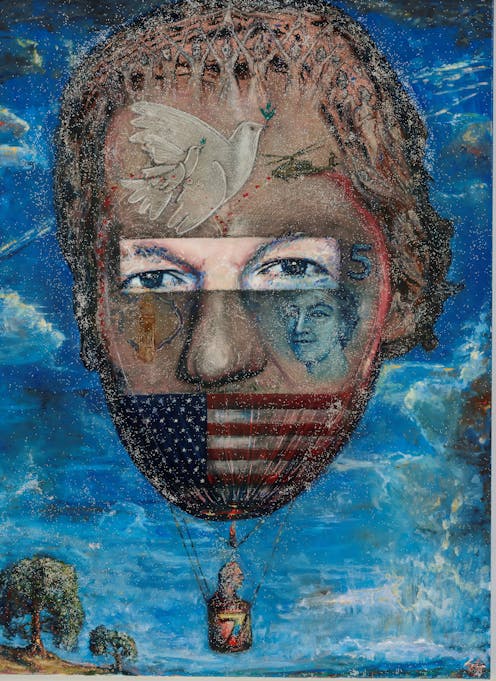

Several entries in this year’s prize, while not being of politicians, can be described as political, as their subjects are the change-makers who prick our conscience. Chief among these is Shaun Gladwell’s A spangled symbolist portrait of Julian Assange floating in reflection (pictured at the top of this article). Assange’s eyes look out from a balloon of his head, gagged by a US flag. An image of the Queen is stamped on one cheek, based on the banknote Gladwell used to sketch Assange during his time in Belmarsh Prison, while below his head is suspended in profile.

It hangs next to Anna Mould’s Complicit, ostensibly a portrait of Joan Ross, but as with Ross’s own work, this is a critique of colonisation. More conventional portraits of newsmakers include Sam Leach’s sensitive portrait of Louise Milligan and Kirsty Nielson’s angst-ridden portrait of Cheng Lei.

Julia Gutman did not exhibit in this year’s Archibald. Instead she has entered the Wynne with Olive, a suspended sculpture of textiles and wire, showing Olive the dog comforting a grieving friend.

Also in the Wynne Prize, the creative duo of Clair Healy and Sean Cordero use flashing lights on their Grey Nomadic Visions. The traditional divisions between different forms of media continue to be dissolved, with Billy Bain’s The fighters incorporating a flag, sewn by his mother.

Juanita McLauchlan’s mudhay burrugarrbuu- bula / Possum Magpie also dissolves the barriers between printing, embroidery and collage to evoke a sense of place. More conventionally, Jenna Mayilema Lee has woven a xanthorrhoea in Grass tree (at rest). But the weaving includes pages from an old dictionary of Aboriginal words.

The dominance of Indigenous artists in this year’s Wynne Prize is a reminder of how John Olsen, who as an art student vocally objected to the trustees’ conservatism, later became a trustee. In his extreme old age he complained to various news media outlets that Aboriginal artists were not painting landscapes. He was, of course, wrong.

Joanna Mendelssohn has in the past received funding from the Australian Research Council

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.