Throughout the mountains of the American West, carvings hidden on the trunks of aspen trees tell the stories of the sheepherders who made them as they passed through with their flocks. Most of the men who etched these arborglyphs into the living trees were Basques who, starting with the Gold Rush of the 1840s, had immigrated from the Basque Country that straddles the Pyrenees Mountains.

Our experience of documenting arborglyphs – “lertxun-marrak” in Basque – has deepened over time. At first, we simply tried to decipher what was on the tree. It can be hard to tell what is scarred bark and what is a carving. Gradually, we got better at deciphering the carvings and now hope to spot the oldest and most ornate.

We also came to appreciate the different styles and themes, like in signatures and writing. One herder carves his name, the date and his hometown; another delves into politics; and another carves a hoped-for female companion.

Viewing the decades-old carvings, we’re surrounded by the quiet and solitude of the high mountain range, whether in the Sierra Nevada, Ruby Mountains or Sawtooth Mountains. We literally stand in the footsteps of the herder who created the arborglyph.

These herders left their marks on the aspens, and now we are part of a research collaboration that aims to document and catalog as many of their arborglyphs and the experiences they record as possible before they disappear. About 25,000 arborglyphs have been documented over time, and there are likely at least as many more left to be recorded before they’re lost.

Who were the sheepherders who left their mark?

Beginning almost 200 years ago, Basques emigrated to the American West to pursue economic opportunities, escape compulsory military service or political persecution, and for other personal reasons. Most were lower class, from agrarian backgrounds, with little to no education or English language skills. As the sheepherding industry grew in the West, it offered these immigrants steady work, and Basques became synonymous with sheepherding through the 1970s, when the economy improved in the Basque Country.

The Basque immigrants practiced a seasonal form of herding called transhumance. The herders trailed the sheep up into the high mountains during the spring and summer for grazing, then migrated in the fall back to the valleys where they spent the winter. This annual cycle meant Basque herders spent their summers alone in the hills.

In Basque, Spanish, French and English, they carved into living aspen trees to express their thoughts, dreams, wishes and challenges. Their arborglyphs cover a spectrum of topics: their hometowns, sports, women, love, work, religion, politics and more.

For example, they carved political slogans like “Gora Euskadi” (“Up with the Basque Country”), for which they could have been arrested at home. There are carvings of crosses that note the festivals of particular saints, boats depicted by those who hailed from fishing villages, and well-known verses and poems about longing to return to their country.

Sometimes you laugh when you get the joke or the saying that they share. Other times, it can be quite moving as they describe their lives and longings. These carvings reflect a variety of human emotions and experiences, with nostalgia playing a prominent role.

Collecting the carvings virtually

To document these disappearing cultural artifacts, we formed Lertxun-Marrak – The Arborglyph Collaborative, composed of Boise State University, California State University, Bakersfield, and the University of Nevada, Reno in collaboration with the Kern County Museum, the Basque Museum, and the Northeastern Nevada Museum, with the support of the National Historical Publications & Records Commission.

We also want to make connections with those who were interested in the carvings: family and friends of those who left the Basque Country for opportunities in the American West; those from local communities who wish to understand the experience of these immigrants; artists who see the aspen trees as a canvas and the carvings as a distinct art; researchers and governmental organizations, hikers, hunters and runners who come upon them in the backcountry, and the greater public.

Unfortunately, age, grazing practices, more frequent and intense fires, and climate change as a whole threaten these carvings. The Arborglyph Collaborative aims to document as many tree carvings as possible before they are gone.

To do so, we follow the herders’ trails through the mountains. It’s easy to walk through an aspen grove and not realize that the bark of the trees are canvases. Having an understanding of the sheepherding area helps us identify groves where herders carved on the aspens. Mature aspen groves with springs close to them are better candidates to contain “lertxun-marrak.” If we find one arborglyph, we can assume that there will be others, since they are usually found in groups in areas with heavy sheepherding traffic.

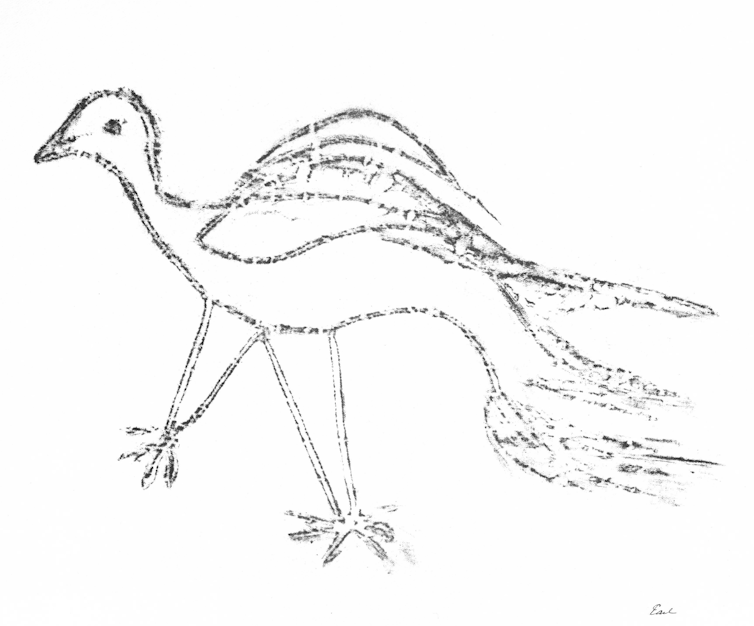

The techniques used to capture and reproduce tree carvings have evolved along with the available technologies. The Earl Collection of tree carving rubbings, deposited at the Jon Bilbao Basque Library at the University of Nevada, Reno, represents one example of the early efforts.

Reno residents Jean and Phillip Earl first heard about arborglyphs during a lecture at the university in the 1970s. Intrigued, they began to actively seek out what they first termed “living galleries” and to experiment with methods of preserving the images they found; muslin and black rubbing wax proved the best tools for the job. The Earls devoted 40 years to developing an archival record comprising around 150 rubbings of the carvings that most captured their attention because of their visual appeal.

Along with rubbings, researchers used sketching, still photography and, later, video recordings to document the etched bark of aspens. Another research collection in the Jon Bilbao Basque Library was compiled by one of the first scholars interested in arborglyphs, Joxe Mallea-Olaetxe. In fact, he coined the term lertxun-marrak – literally, “lines/drawings on aspen trees,” the name for arborglyphs in Euskara, the Basque language.

From the 1970s to the 2000s, he documented thousands of arborglyphs, including detailed descriptions, photographs and video recordings, providing a comprehensive view of these cultural artifacts.

Now, we are able to document the arborglyphs with photogrammetry, which creates a three-dimensional model in realistic detail. We’re also able to recreate the carving and its setting in virtual reality, allowing a visitor to immerse themselves in a grove without needing to travel. Smartphones and tablets make it convenient for nearly anyone to engage with arborglyphs from anywhere, at any time, including creating and accessing 3D models of the carvings.

The trees and the Basques

The need to preserve these human experiences transformed into artifacts is driven home by encounters like one that happened on a recent documenting trip in the mountains outside of Idaho City, Idaho. One student who was helping take photos and videos and noting GPS locations revealed that her father came to the U.S. from the Basque Country to work as a sheepherder. She’d joined our research team to learn more about his experience. When she found the carvings made by her dad, who had died when she was young, tears ran down her cheeks as she experienced a flood of emotions.

Stories like this demonstrate the value of preserving these artifacts that revive the voices and memories of these immigrants in the American West. Today, increased technological availability and reliable partners are key to achieving this goal. We have much more work to do, more arborglyphs to collect, ways to make them publicly accessible, and more communities to engage with.

John Bieter receives funding from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission. In 2023, the research group Lertxun-marrak/The Arborglyph Collaborative of which the author is part received $25,000 from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission to support the project.

Iñaki Arrieta Baro receives funding from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission. In 2023, the research group Lertxun-marrak/The Arborglyph Collaborative of which the author is part received $25,000 from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission to support the project.

Cheryl Oestreicher does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.