It’s a great pub quiz question. What’s the fastest human beings have ever travelled? And what were they travelling in when they did it? No it’s not Lewis Hamilton in a 200mph Mercedes Formula 1 car. The answer is a whopping 24,791mph and the men who did it were sitting in a metal cone with less space inside than a family hatchback. That’s quick. Even the world’s fastest fighter jets struggle to muster 2000mph.

That metal cone, part of the Apollo 10spacecraft, was launched towards the moon atop a huge Saturn V rocket in May 1969, and is the only part that returned to Earth. It now resides in London’s Science Museum. Apollo 10 was the dry run for the moon landing that would, just two months later, entrance the entire planet. And while the attention of the world will once again focus on the deeds of Apollo 11 and its crew when the 50th anniversary rolls round in July, its lesser-known sibling also deserves its moment in the spotlight. For if things had gone badly in May, Neil Armstrong would not have been making his “small step” onto the moon’s surface on 21 July.

“It was the dress rehearsal for Apollo 11,” says Doug Millard, a senior curator at the Science Museum and the man overseeing the priceless spacecraft in London. “If it had gone wrong, that would have put the programme back months, and John F Kennedy had promised that America would have a man on the moon – and returned safely – by the end of the decade.”

Amazingly, it came only two years after three astronauts had perished in the Apollo 1 fire that almost brought the United States’ space programme to a standstill. “With that in mind, had Apollo 10 failed catastrophically it could have ended the entire programme,” points out Millard. “Public opinion had already been damaged by Apollo 1 and with the Vietnam war taking up America’s priorities and cash elsewhere, appetite for spaceflight would have dwindled.”

The Cold War was waging, and the US and the Soviet Union were embroiled in proxy wars on Earth but also fighting for supremacy in space. The race to the moon was, of course, ideological as much (if not more) as it was scientific. After launching the world’s first artificial satellite – Sputnik 1, the first man in space – Yuri Gagarin, and the first man to walk in space – Alexei Leonov, the Soviet Union had taken an early lead. But once Nasa was revamped and reorganised in the mid-1960s the Americans had gained the upper hand.

Millard agrees that space had become yet another proxy war for the competing political doctrines of the two nations, and there were many people with a more grounded world view insisting that the money spent in space would be better redirected towards solving earthbound problems. But Millard posits an interesting counter view: “If the proxy war in space avoided a real war between nuclear powers on Earth, then it was arguably money well spent,” he says.

“Apollo 10 was a learning mission,” he goes on. “If it had experienced non-catastrophic failure, the programme would have continued, but Apollo 11 would then have become the second dress-rehearsal, and Apollo 12 would have become the landing party, and so on.”

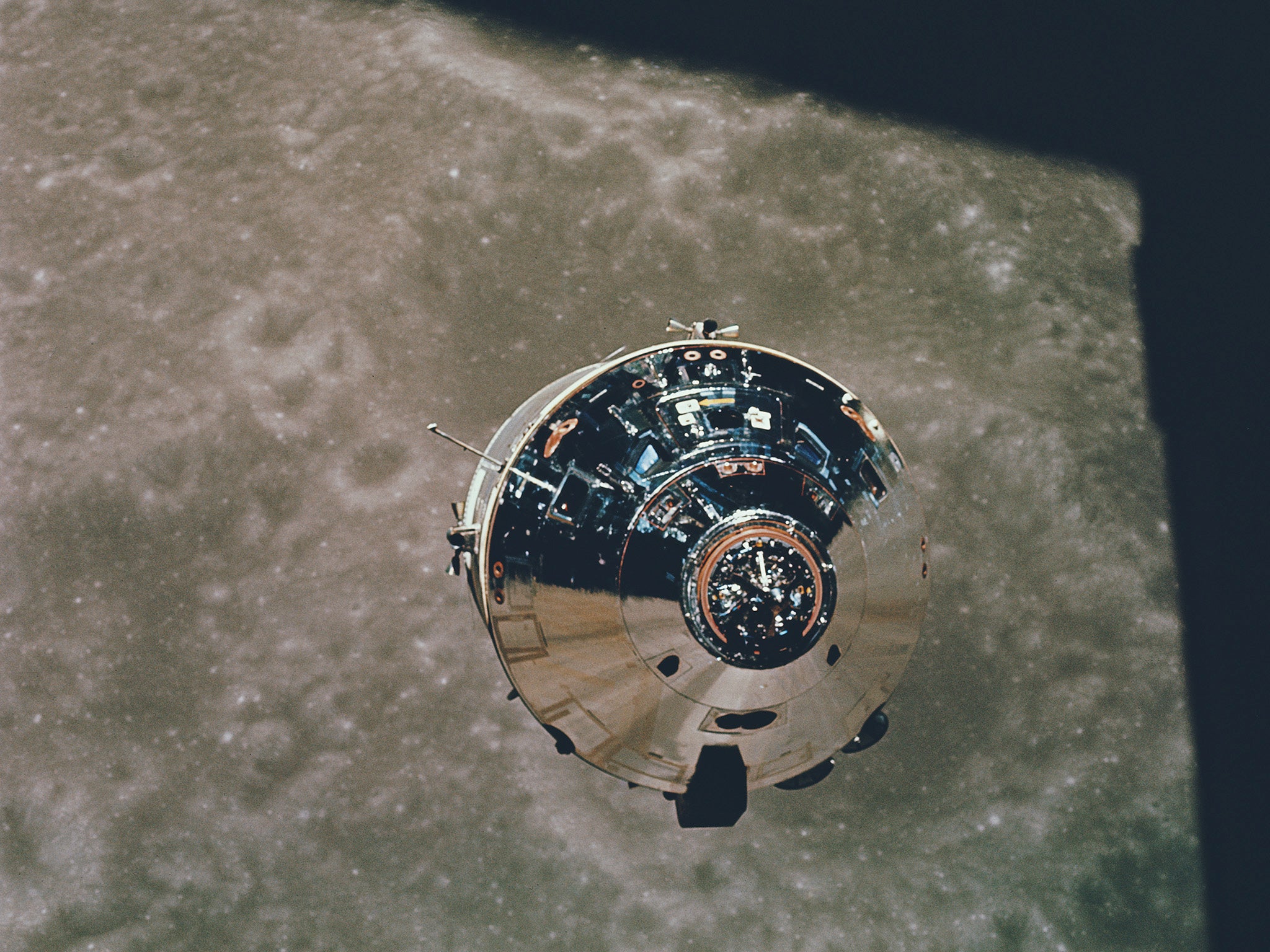

Eugene Cernan, John Young and commander Thomas Stafford blasted off from Cape Kennedy (now Cape Canaveral) on 18 May. They circumnavigated the moon as Apollo 8 had done five months earlier and carried out the manoeuvres necessary if a spacecraft was to land on the surface. The command module (the part of the spacecraft now in London and the only section of any Apollo mission that would return to Earth) docked with and separated from the lunar module – the four-footed lander that would carry astronauts to the surface.

Later the lunar module would fly to within 8.4 miles of the moon, the closest at that point humans had come to the surface. Cernan said they seemed so near it was like flying a jet among the craters: “So close all you have to do it put your tail wheel down”. And just in case the astronauts were tempted to land, the lunar module was short-fuelled – they knew they’d be going to their graves if they tried.

Which doesn’t mean to say that inside the lander Cernan and Stafford weren’t tempted. “Who wouldn’t be?” remarked Stafford afterwards. Cernan would later walk on the moon, being the last man ever to do so on Apollo 17. But Stafford never made it.

It was during this fly-by phase that the mission came closest to ignominious and calamitous failure. The lunar module rolled violently under engine ignition. It lasted 8 seconds but as Cernan said afterwards “you have no idea how long 8 seconds can be”. It was a frightening moment only tempered by the discovery that it was caused by human error, not a problem with the spacecraft itself, which meant Apollo 11 was still on track.

But while the incident was initially downplayed – “the machine did something unexpected” said Mission Control flight director Glynn Lunney – if there had been just another few rolls of the module it would have plummeted on to the moon’s surface. It was the kind of catastrophic failure Millard mentioned. Had it happened there would have been no “giant leap for mankind” two months later. Of course, we now know there was.

“What the Apollo programme shows is the incredible achievements humans can perform if they set their minds to it,” Millard says. “That cohort of American military engineers and technicians was the last generation to live through the Second World War, growing up with a command structure which lived on in Nasa and drove the Apollo programme.

Their aviation and military expertise, along with a team of younger technicians with limitless ambition to find the right solutions, meant that no opportunity was missed.” We think of the Soviet Union as a huge military and industrial machine “but in many ways Nasa out-Sovieted the Soviets”, adds Millard.

London’s is the only Apollo spacecraft outside the United States, all the others were eventually recalled, so the city is privileged indeed. Arriving on loan in 1976 the spacecraft has spent longer in the UK than in its home country.

Standing in front of the ageing capsule in the Science Museum, it seems impossible that this was the most technologically advanced vehicle on (and above) the planet in 1969. Its stainless steel exterior is a dull brown, almost rusty, colour and its crumbling heat shield – which protected the astronauts from the intense frictional heat of more than 2,500C as the craft re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere – looks like crumbling barbecue charcoal. It stands a mere 3.48 metres high and is 3.91 metres across its base (the Saturn V rocket which blasted it out of the Earth’s atmosphere and on to the moon was, by comparison, 111 metres high).

There barely seems to be space inside for a single human, let alone three plus the bulky control and life-support systems needed to run it. How anybody could fly to the moon and back in what looks like little more than a overgrown can of beans defies belief. Yet it often goes unnoticed by visitors. Looking more Heath Robinson than space age, many people walk by without even knowing what it actually is.

All of which is most ironic because the command module was nicknamed Charlie Brown by the crew, and Charlie Brown – as everybody knows – was the little kid ignored at summer camp every year…

But at least as far as the Science Museum is concerned Apollo 10 will have one more day in the sun. From 23 May the museum will present its Summer of Space where Apollo 10 will take pride of place alongside British astronaut Tim Peake’s Soyuz capsule as the latter ends its nationwide tour. There will be workshops, gallery tours and other Apollo artefacts never before seen in Britain.

And what about that record? As it approached the Earth’s atmosphere on its return journey Apollo 10 hit the fastest speed a human-built object has ever achieved. But why did it fly faster than other moon missions? Unencumbered by rocks and specimens from the moon’s surface, plus a bit of tweaking with the thrusters to use up extra fuel left over from when the lunar module excursion was aborted because of the violent rolling, Apollo 10 was able to travel faster than its fellow spacecraft, and it’s a record that still stands today.

Alongside another – apparently Tom Stafford was the first person to swear in space (or at least the first to be heard doing so back on Earth). Oh, and Apollo 10 was the first space mission to carry pornography aboard (which, to be fair, was put there by the ground crew without the astronauts’ prior knowledge). All of which is more information than you’ll probably need when you’re in the Red Lion quiz team.