A 69-million-year-old skull found in Antarctica belonged to what scientists say is the oldest known modern bird.

An early relative of the continent’s ducks and geese, it lived off the Antarctic coast during the Cretaceous Period, at around the same time as the famous Tyrannosaurus rex.

“This fossil underscores that Antarctica has much to tell us about the earliest stages of modern bird evolution,” Dr. Patrick O’Connor, a professor at Ohio University and the director of Earth and Space Sciences at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, said in a statement announcing the finding.

O’Connor is the co-author of a related study published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

It was found during an expedition in 2011 by the Antarctic Peninsula Paleontology Project. Understanding how the region helped to shape modern ecosystems is currently being researched.

“Antarctica is in many ways the final frontier for humanity’s understanding of life during the Age of Dinosaurs,” said co-author Dr. Matthew Lamanna, of Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

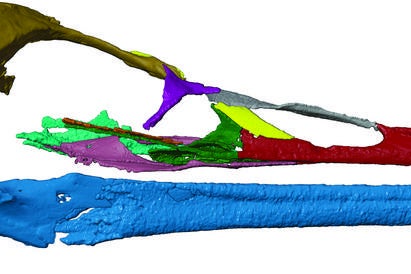

The skull itself is long, with a pointed beak and a brain shape that is unique among all known birds previously discovered from the Mesozoic Era, which includes the Cretaceous Period. The features, the researchers said, belong to an extinct bird named Vegavis iaai — and place it in the group that includes all modern birds.

Vegavis was first reported 20 years ago by University of Texas at Austin co-author Dr. Julia Clarke. It was proposed to be an early member of modern waterfowl like ducks and geese. But, such birds are exceptionally rare before the end-Cretaceous extinction event and this study is the first with a nearly complete skull.

The skull has preserved its powerful jaw muscles, unlike today’s waterfowl, and its features are consistent with clues suggesting that Vegavis used its feet to propel itself underwater.

“Few birds are as likely to start as many arguments among paleontologists as Vegavis,” says lead author Dr. Christopher Torres, a National Science Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow at Ohio University’s Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, said. “This new fossil is going to help resolve a lot of those arguments. Chief among them: where is Vegavis perched in the bird tree of life?”