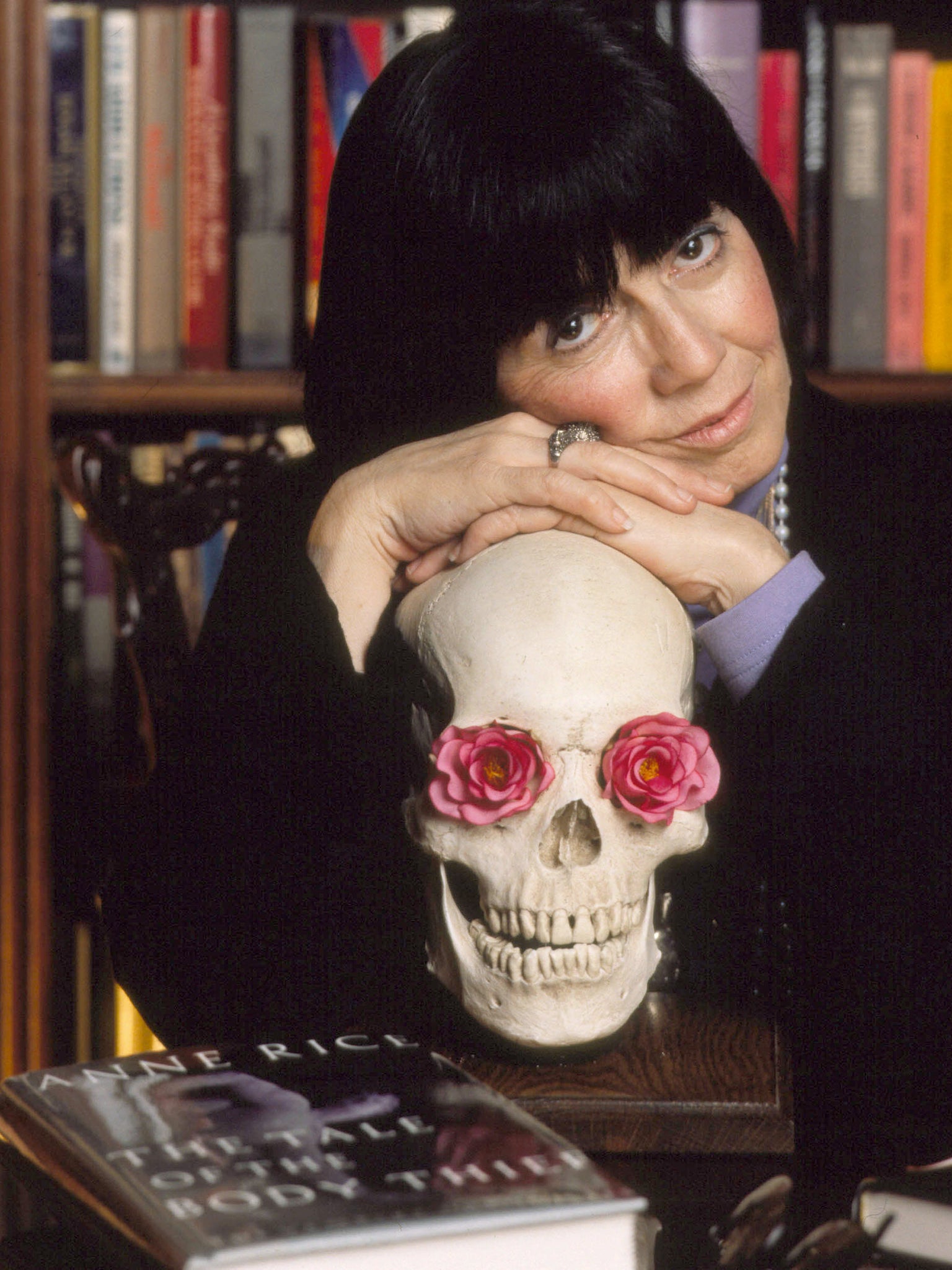

Anne Rice, a gothic novelist who helped resurrect the vampire story with dark and seductive bestsellers such as Interview with the Vampire, which was adapted into a hit movie and used the bloodsucking folk creature as a way to examine mortality, sexuality and life on the margins, has died aged 80.

A New Orleans native who set many of her books in the city’s riverfront bars, raucous gambling dens and dark oak-lined streets, Rice wrote more than 30 novels that together sold in excess of 150 million copies. Although she moved far beyond gothic horror, spinning tales of 18th-century Italy and whip-snapping erotica, she remained best known for her vampire novels, which acquired a devoted following among readers who saw part of themselves in her lonely protagonists, who search for companionship and redemption even as they read minds, cry tears of blood and try to stay away from fire and the sun.

“Her refugees from sunlight are symbols of the walking alienated, those of us who by choice or not dwell on the fringe,” wrote Matthew Gilbert, reviewing her novel The Queen of the Damned (1988) for The Boston Globe. Profiling Rice for The New York Times, Susan Ferraro noted that her vampires “are lonely, prisoners of circumstance, compulsive sinners, full of self-loathing and doubt. They are, in short, Everyman Eternal.”

Rice had mixed views on the supernatural. She didn’t believe in vampires but allowed that ghosts might exist. But she was certain that something unusual happened to her around 1970, shortly before she launched her literary career, when she was raising her young daughter in the bay area and studying for a master’s degree in creative writing. She had what she later described as “a horrible, horrible dream” – “a prophetic dream of my daughter dying of something wrong with her blood”.

Her daughter, Michele, was soon afterwards diagnosed with leukaemia. She died in 1972, a month before her sixth birthday. Overcome with grief, Rice immersed herself in a lyrical short story she had started a few years earlier, about a journalist interviewing a vampire named Louis. She added a new character, Claudia, a child vampire with blonde hair like Michele’s; an anti-hero character, the vampire Lestat, was modelled after her husband, poet and painter Stan Rice.

Writing about Louis, who had become a vampire in 1791, she found herself writing about her own life. “I really got into the character,” she told the Times. “For the first time, I was able to describe my reality, the dark, gothic influence on my childhood. It’s not fantasy for me.”

The story grew into her first novel, Interview with the Vampire (1976), which kicked off The Vampire Chronicles, a 13-volume series populated by androgynous-looking vampires, ancient Egyptian rulers and undead rock stars, as well as a few mere mortals. The book was adapted into a 1994 movie directed by Neil Jordan, starring Brad Pitt and Tom Cruise, and turned Rice into a literary phenomenon.

Some critics scoffed at her work, calling her characters underdeveloped and her prose overwrought. “To pretend that it has any purpose beyond suckling eroticism is rank hypocrisy,” Edith Milton wrote in The New Republic, reviewing Rice’s first novel. The second instalment of The Vampire Chronicles, The Vampire Lestat (1985), had “lugubrious, cliche-ridden sentences that repeat every idea and sentiment a couple or more times,” said Times book critic Michiko Kakutani.

Yet Rice’s books continued to sell and helped bring vampires back into popular culture, years before the release of Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight series or TV shows such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer, True Blood and The Vampire Diaries. The third instalment of The Vampire Chronicles, The Queen of the Damned, was adapted into a 2002 movie, and the series inspired a 2006 Broadway musical, Lestat, with a score by Elton John and Bernie Taupin.

“Anne was a fierce storyteller who wrote large, lived quietly, and imagined worlds on a grand scale,” her long-time editor at Knopf, Victoria Wilson, said in a statement. “She summoned the feelings of an age long before we knew what they were. As a writer, she was decades ahead of her time.”

After the negative reviews for her first novel, Rice decided to explore fresh literary terrain, taking a break from the gothic to write The Feast of All Saints (1979), a historical novel about free people of colour who lived in New Orleans before the civil war, and Cry to Heaven (1982), about castrated opera singers with a high vocal range. “In these books, she writes rich, elegant prose in a baroque style, as though each word is laid on velvet and encrusted with jewels,” Washington Post journalist Sarah Booth Conroy later wrote.

Rice also wrote erotic novels under a pair of pen names – partly, she said, because she didn’t want her father to know about the books. As Anne Rampling, she wrote Exit to Eden (1985), which was adapted into a poorly received 1994 film comedy, and as AN Roquelaure, she wrote the Sleeping Beauty Quartet, a four-volume BDSM series that she said was set in a medieval fantasy world “of discipline, love and surrender, for the enjoyment of men and women”.

“I’m a divided person with different voices, like an actor playing different roles,” she told the Times in 1988, describing her various literary personalities. She added that when it came to her Sleeping Beauty books, “I wanted to write the kind of delicious S&M fantasies I’d looked for but couldn’t find anywhere. I’m really rather proud of it, shocking though that might be. I feel that if I’m read 200 years from now, it’ll be as much for that as anything else.”

Howard Allen O’Brien was born in New Orleans on 4 October 1941. She was named for her father, a postal worker and Second World War veteran – Rice later recalled that her mother had thought that “naming a woman Howard was going to give that woman an unusual advantage in the world” – and started using the name Anne on her first day of school.

When she was 15, her mother died. Rice said the cause was alcoholism, and immortalised her in fiction, turning her into the title character’s mother, Gabrielle, in The Vampire Lestat. “When I lost my mother, I lost the one person in the world who was really interested in me, interested in me in a selfless way,” she said.

Her father moved the family to north Texas, where Rice graduated from high school in Richardson, studied at Texas Woman’s University and North Texas State College in Denton, and met Stan Rice. They married in 1961 and moved west, enrolling at San Francisco State College (now a university), where her husband became an English professor and led the creative writing department. She received a bachelor’s degree in political science in 1964 and a master’s in creative writing in 1972.

By then, she had started writing gothic short stories, her imagination fired by 1930s horror movies such as Dracula’s Daughter more than classic works of vampire literature. But after her daughter died, alcohol increasingly took over her life – “All I wanted to do was read and drink,” Rice said – until 1979, when she and her husband quit drinking upon the birth of their son. The family moved to New Orleans in the late 1980s, settling a few blocks from where Rice grew up, in a 19th-century home that served as the setting for The Witching Hour (1990), the first volume in a gothic trilogy known as the Lives of the Mayfair Witches.

After her husband’s death in 2002, Rice announced that she would conclude The Vampire Chronicles the next year with Blood Canticle. She resumed the saga in 2014 and also collaborated with her son, Christopher, on novels including Ramses the Damned: The Reign of Osiris, which is slated for publication in February 2022.

In addition to her son, survivors include three sisters.

Rice wrote frequently about religion, chronicling her Roman Catholic childhood, her turn toward atheism at age 18 and her subsequent return to the Catholic Church in a memoir, Called Out of Darkness (2008). She also wrote two well-reviewed novels about the life of Jesus, beginning with Christ the Lord: Out of Egypt (2005), before announcing in 2010 that while she remained “committed to Christ” she had “quit being a Christian”, angered by the Catholic Church’s opposition to same-sex marriage. (Many readers saw her vampire novels as a gay allegory, a reading that she welcomed but said was unintentional.)

“I found what the characters in the vampire novels were looking for,” she told NPR, looking back on the religious awakening that had led her back to Catholicism in 1998. “They were groping in the darkness. They lived in a world without God. I found God, but that doesn’t mean that I have to be a supporting member of any organised religion.”

Even as she hopped between genres, she once told her alma mater in an interview, her central theme remained the same: “How we save ourselves, or how we get saved.”

Anne Rice, novelist, born 4 October 1941, died 11 December 2021

© The Washington Post