By his own judgement, Andy Summers does not like to be idle. Isn’t suited to a life of leisure. The late-March morning when we talk is a case in point. Only just returned to his home in Los Angeles from playing a run of shows in Brazil with his Police tribute band Call The Police, he was up early editing the file of photographs he took on the trip. Photography is Summers’s other great passion, seriously so. His black-and-white portraits are handsome and enigmatic. Rumpled hotel rooms and nocturnal ephemera are a speciality, the locations the exotic preserve of the globe-trotting rock superstar.

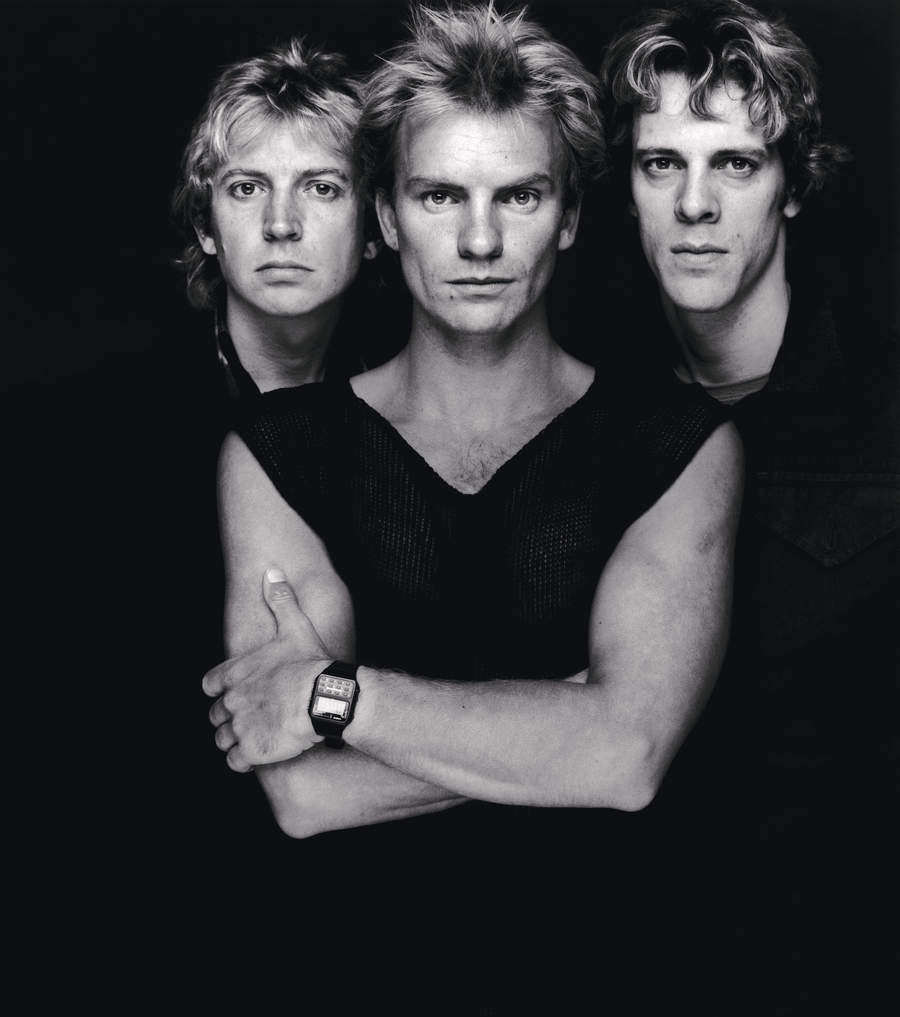

Now a spry 80-year-old, Summers has been famous for six decades as one third of The Police alongside Sting and Stewart Copeland. The band have sold 80 million records and counting, their run of hits beginning with Roxanne in April 1979. They’ve broken up twice, in 1985 and then again in 2008, rancorously on both occasions. Ten years older than both of his erstwhile bandmates, Summers was well-established as a guitarist before The Police and has continued to plough his own furrow apart from the band.

Born in the Lancashire market town of Poulton-le-Fylde on New Year’s Eve, 1942, he grew up in Bournemouth, and took piano lessons before picking up the guitar. At 19 he relocated to London with his friend Zoot Money. Operating as Zoot Money’s Big Roll Band, they gained a foothold on the capital’s then blossoming R&B club scene.

By London’s Summer of Love in 1967, he and Money were garbed in white robes and kaftans and playing psychedelic rock with the short-lived Dantalian’s Chariot. Afterwards, Summers passed through the line-ups of Soft Machine and Eric Burdon And The Animals, before moving to LA for five years, where he studied classical guitar and composition at California State University.

Returning to London in 1972, he soon established himself as a regular on the session circuit. On October 26, 1975, he filled in for Mike Oldfield to perform Tubular Bells with the Northern Concert Orchestra at Newcastle City Hall. Opening the show that night was local band Last Exit, whose singer and bassist was Sting. Eighteen months later, Summers joined ex-Gong bassist Mike Howlett’s Strontium 90, which also included Sting and Curved Air’s American former drummer Stewart Copeland.

Sting and Copeland, along with Corsican guitarist Henry Padovani, were already operating as The Police, and invited Summers to join. After a very brief spell as a four-piece, Summers supplanted the barely competent Padovani in The Police and within six years they were the biggest band in the world.

Tomorrow Summers flies to London, where he will open his latest photography show, Harmonics Of The Night/A Series Of Glances, at the Leica Gallery in Mayfair. Previously he has exhibited in the US, Japan, Australia, Canada, France and Spain. He has a tie-in book being published, too, also titled A Series Of Glances. He answers the phone sounding interrupted, somewhat grumpy, but he warms up talking about his photography.

“‘Passion’ is actually the wrong word for it,” he says. “And it’s not a mere hobby, but a whole other part of my life.”

When did you start taking photographs seriously?

In 1979, when I was relentlessly on tour with The Police. We were surrounded by photographers all the time. Pretty much all of them women. I started to get interested in their cameras and gear. It was all very groovy and hip. They’d all turn up dressed in black, shouting instructions. I started when we arrived in New York. It gave me something to do. Even at that point, I told myself: “I’m going to get good at this.”

I had no idea I’d any talent for it, but I became quite fanatical. It’s like playing music, you get better at it if you do it a lot and if you study. I was very lucky, I was in New York a great deal and I became friends with probably the world’s greatest photographer, Ralph Gibson. He mentored me, and because of my friendship with him I got very deep into the inner circle of photography at the time.

In many of your photographs there’s a sense of melancholy and loneliness, particularly in those of hotel rooms. Is that the lot of the touring musician?

Well, yes. Also, I don’t want to take funny photographs. It must be something that either catches me in a formal, photographic way, or in an emotional way. You can get shitty pictures of hotel rooms, or you can make them a bit more artful. The subject matter in a way is secondary to one’s visual sense. You can make the seemingly more ordinary appear interesting. I suppose you could say I have an eye for it.

Tell me about an arresting photograph of yours titled Man Horse. The two subjects of the title are almost up to their necks in the ocean, together but facing in opposite directions. As if posed in the surf. What was going on there?

That’s a favourite of mine. It was a great moment. One’s mind was prepared. Me, Stewart and Sting were fudging around the edge of the island of Montserrat. We had gone out on a little picnic. The only way you could get around to the spot we’d chosen was by boat. As we arrived at the beach, I spotted that guy leading his horse into the ocean. I immediately saw there was something extraordinary there, a picture. I leapt over the side of the boat, up to my chin in water too, and took a few shots of the guy and his horse. There must be some sort of hook for a photograph to come off, like a song.

What images from your childhood come to you most vividly?

I grew up in the English countryside. So they would be typical of the time: playing in the woods and wearing cowboy outfits, hiding in trees and all that kind of normal stuff. England was somewhat more rural and wilder then. I grew up by a beautiful river and a mill house. Ispent my childhood out in nature. A real nature boy.

Can you recall the first piece of music that struck you, and why?

It would be something like Wonderful Copenhagen. I saw the film it was taken from with Danny Kaye [Hans Christian Andersen, 1952]. It’s a very melodic, lovely, upbeat piece. I learnt to play it on the piano. I played a lot of music as a kid. Piano and then guitar. I had piano lessons at the insistence of my mother. I guess I was a natural musician. It’s a gift. You’re born with it. You can learn art forms, but there’s an inherent aspect you must have.

I tried being a painter for a few years. I finally stopped after five or six years because I realised it wasn’t natural to me. I could sort of create a good painting with oils, but I hadn’t got the ‘thing’ born into my hands. Same with music. You can learn and get pretty good at it, but you’re never going to be better than the person who has it naturally.

When was the first time you played music in front of an audience?

I was eleven or twelve, singing and playing on guitar an old folk song called Tom Dooley in front of the whole school. That was when the bug bit, as a boy, and it’s never left me. If you were a kid with a guitar and you got up on stage, you were an attraction. The string of girls grew hugely at that point. I quickly grasped that part of it as well.

As a teenager, you started to play around Bournemouth with Zoot Money, and then the two of you went off together to London. What did you think of London in 1962?

It was an incredibly scary place. Zoot and me had a thing and it was me who prompted the move. Isaid to him: “We have to go to London.” We didn’t know how we were going to survive. We didn’t know anything. Somehow we got ourselves a basement flat in West Kensington. Then we got our drummer up from Bournemouth, and were put in touch with a second guy, Paul Williams. Paul didn’t play an instrument, but we needed a bass player and he offered. He’d never even picked a bass up, but he was another natural musician. It was very risky stuff, because we didn’t have a gig at all.

We managed to land an audition at a place called the Flamingo Club in Soho for a guy named Rick Gunnell. He offered us a gig as the new house band. We were good. Zoot was a great singer. From there we started playing all over the country. We still weren’t even out of our teens. The Flamingo Club was very dodgy. It was a late-night place, the audience mostly criminals. Prostitutes, drug dealers, the Kray twins. Boy, talk about being chucked into Dante’s Inferno. We played six sets a night. An incredible training ground to a drunk, stoned, out-oforder crowd, packed to the brim. Eric Clapton also played there. John Mayall, Peter Green and Albert Lee, too. It was the nest we all came from.

From there you leapt into the head trip of Dantalian’s Chariot.

The ridiculously named Dantalian’s Chariot. It was the glorious sixties, and you wanted to be a part of all that. What can I tell you, there were a lot of drugs around in the scene. So we abandoned our great rhythm and blues band. I mean, it’s a bit tragic when you think back on it, but that’s life. Being young and making terrible mistakes. We started to play at places like Middle Earth, The Roundhouse. The acid era. There was so much stuff opening to us in the moment. There were a lot of influences going on.

We began to embrace world music. Ravi Shankar. The Beatles discovering Indian music. Miles Davis was playing a more modal sort of music. John Coltrane and Bill Evans were around. That was what was musically in the air. We moved away from Ray Charles and James Brown and into this droning kind of music. I got to play these long, psychedelic guitar solos. Not the twelve-bar blues, but something else altogether. It was the whole ethos of the period, and it suited me very much.”

Going off to formally study music can’t have been typical of the time?

I’d just had enough of the band thing. I’d done it for five years. I came to the US with Soft Machine, and then after I left them I was in The Animals. From being in West Kensington, I was suddenly living in Laurel Canyon with Eric Burdon. It was a totally different scene, very trippy. A head-turning experience. The thing with Eric came to an end and I came back to England. But I didn’t like it. I went straight back out to California. Everything changed for me. I was in LA. I had an LA girlfriend. I was a very serious musician and I just wanted to get deeper into musical theory. I did that and I really enjoyed going to college.

This quest for self-improvement seems to have been a constant theme.

All the time. It’s a lifetime of improvement. At college I played classical guitar, studied harmony. It was being submerged in the thing itself, not just trying to get your face out on stage. I’d had all of that already. All the ridiculous scenarios you go through, the sex, drugs and rock’n’roll. I studied and played guitar relentlessly, until the whole thing wore out and I had to come back to London once more. It was a fertile period. Like the cliché where you go out into the desert for forty days and come back renewed. I got given a Telecaster, too, and that turned the whole thing around for me again.

Back in London, you did sessions for a range of artists including Joan Armatrading, Jon Lord, David Essex and easy-listening star Neil Sedaka. What did those jobs mean to you at the time?

Nothing much besides survival. I was able to play pretty much anything with anybody by then, so that’s what I did. Playing with Neil Sedaka was great fun, and it came to me exactly when I was in desperate need of money. It was a great offer. We did the Royal Festival Hall. Neil adored me and we got on very well. He’s a great songwriter and an extremely good musician. He can play the shit out of the piano.

Summers joining The Police was a halting affair. He heard an early version of Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic at Mike Howlett’s house. Howlett played it to him on a tape recorder in his bedroom.

“I thought it was rubbish,” Summers proclaims. “Henry Padovani could hardly play. By coincidence, I’d also met Stewart once before, up in Newcastle. I was doing a gig with Kevin Ayers, and he was there playing with Curved Air. We all ended up in the same hotel. Lying on the floor of one room, smoking and drinking beer and looking up at the ceiling. I remember thinking: ‘Boy, that guy can talk.’”

Despite his first impressions, Summers kept in touch with Sting after Strontium 90 dissolved. Eventually, Sting coerced him into The Police, initially as the band’s second guitarist. They played only a couple of gigs as a four-piece, touting themselves as a punk band.

“Stewart was very intent upon being punk,” Summers says. “Henry seemed to fit that much more than I did. I was too educated for punk rock, too good for it. On another planet. Poor Henry got the boot, and I went into it full-time.”

Copeland’s elder brother, Miles, who soon progressed to being their manager, put up the £1,500 it cost them to make their debut album, Outlandos d’Amour. They recorded intermittently over a six-month period from January 1978, holed up at a poky studio in Leatherhead, Surrey, above a dairy.

A&M Records signed them on the strength of the song Roxanne, but initially at least, The Police were a slow burn. The album scarcely made a ripple upon its release in November 1978. It took six more months, and reissues of Roxanne and Can’t Stand Losing You, for them to achieve lift-off.

How accurate did your first impressions of The Police prove to be?

I felt there was something there. Sting and Stewart were both pretty rough players. They were supposed to be a punk band, but they weren’t really. They were playing with the attitude of punk, though, so it was very fast and a bit out of time. Not really all that good. But I kept going with it. The first time I thought “Hang on a minute…” was when Sting told me he’d got this new song he wanted to show me, which was Visions Of The Night. There was an edge to it, and I found it exciting. Not tired at all, full of energy.

Apparently Miles Copeland was afraid that your joining would damage The Police’s punk cred.

He was dead wrong. Miles is full of it. There’s a difference between attitude, and trying to be what’s current, and real music. I saved the band’s life. Basically, Sting came to life when I joined. All the songs started to come out. The natural ability he had could be released through me. It never would have happened with Henry.

At one early point, weren’t you lined up to record with John Cale?

John was supposed to be the record producer. But he turned up and he was drunk out of his mind. Hopeless. It just didn’t work out. I think he pissed off after about half an hour. Nothing came of it. Later I found myself on a TV show with John in Spain. On that occasion he rolled around on the floor and tried to stick an American Express card up his nose, because it had cocaine on it. Talented guy, but it all went a bit south for him.

In 1979 The Police undertook their breakthrough US tour cooped in a Ford transit van. What did you learn from being in such proximity to each other?

That I was working with two total arseholes. I struggled on. It’s usually humour that saves the day. When you spend as much time as we did together, 24/7, and you’re travelling hundreds of miles a day in a van, you develop a collective mind. It’s very dark, and funny usually. Very ironic and deprecating. You kind of bond through the travel. We weren’t fighting for five hundred miles. It would mostly be irony, shit food and trying to sleep. That’s the life in the initial stages, at least. It’s not the life any more, believe you me.

Sting was the band’s songwriter. The actual songs, though, were the work of the three of you in the band, weren’t they?

Absolutely. Let’s call them tracks. The Police’s tracks were made because of the chemistry that existed between the three of us. There’s no way you can duplicate that. Of course, it’s been said five million times over: “We could have done that.” Well, you couldn’t, and you didn’t. The Police was a one-off. If one guy had disappeared from the three, it wouldn’t have happened. Take Every Breath You Take. God, it wasn’t even going to go on the Synchronicity record until I put that guitar part on it.

You did win a Grammy for Behind My Camel, the instrumental track you contributed to the third Police album, 1980’s Zenyatta Mondatta.

I did. And I was very pleased. But I could have won a Grammy for anything at that point. I could have farted and it would have got a Grammy.

Following on from 1979’s Regatta de Blanc (Message In A Bottle, Walking On The Moon), Zenyatta Mondatta (Don’t Stand So Close To Me, De Do Do Do, De Da Da Da) was the second of four consecutive UK No.1 albums for The Police. Their fifth and final studio album, 1983’s Synchronicity, also topped the Billboard chart in the US.

They supported Synchronicity with a stadium tour of the US, including a 70,000 sell-out at Shea Stadium in NYC. But by then the three of them were already breaking up. Relations between them had become so strained that they had made Synchronicity from three separate rooms at AIR Studios in Monserrat. They reconvened in London in July 1986, meaning to make a new record. But the sessions soon collapsed, and soon after The Police disbanded.

From 1978 to 1983 you kept up a relentless recording and touring schedule with The Police.

It was a whirlwind. We were so incredibly popular, not just in England but everywhere in the world. Japan, even fucking India. All over. Basically we were always on tour. We never stopped. We were making a lot of money, so the manager never wanted us to rest. It was exhilarating and wonderful, and exhausting. An amazing experience.

To be that popular and that recognised everywhere you went. It got so you couldn’t leave the house in the end. Or a hotel room. It was this sort of clichéd, fantasy world and we inhabited it for a very long time. It’s gone now, all changed with the internet. I think we had the height of the golden period, the glory years.

The flip-side to working to such a degree is the personal toll. You went through a divorce in 1981. How can you ever weigh that cost?

It’s a very hard thing to balance. There’s the shadow side to it. I was married, we had a baby. My very smart and successful wife, Kate, after we got to a point, she told me: “That’s it. I’ve had enough. Not any more for me.” You can imagine the life I was leading. If you’re a woman, married to a bloke, and he’s got hundreds of other women coming after him every day… I don’t have to be explicit here. You see where I’m going. Trying to balance that with a wife and a kid. And I’d had to go into tax exile.

So yes, we got divorced. Same with Sting and Stewart. They both got divorced too. Proper partnerships and marriages don’t go with a band at the fantastical point we were at. The happy part for me is Kate and I got back together four years later, once the insanity was all over.

How seriously did the three of you try to make a follow-up to Synchronicity?

That was a complete fuck-up. Everyone was desperate for us to get together again. Sting was off on his own. He’d made his solo record [1985’s The Dream Of The Blue Turtles]. We were going to have a trial run at a studio in North London. Stewart went out on a horse the day before we started. Stewart was playing polo in those days. He fell off the horse, broke his collar bone and couldn’t play the drums. That was the end of it. And Sting didn’t want to write new songs. So all we did was a wanky new version of Don’t Stand So Close To Me. It was a pretty limp affair. If Stewart hadn’t come off his bloody horse it could have been a different story.

What’s the immediate sense you have when you’ve been through such an intense experience and then, at a stroke, it’s vanished from your life?

A huge sense of loss. I found it incredible. After all the noise and adulation for years on end, suddenly it’s not there any more. You are now famous. What are you going to do? Start all over again, go back to the music. And I did. I made XYZ [his first solo album of 1987].

Then I moved back out to California and started to make instrumental records. So my recovery was all through the music. In my case, I did get back with my wife, and Kate got pregnant with twins. I got a studio. It was sort of a rebuilding of a life. The difference being, now you’ve got some money and you’re well-known, and so everyone’s interested still. It wasn’t as if you were starting from ground zero. You just had to be very good with whatever you put out.

Altogether, Summers has made 13 solo albums, most of them instrumental, the latest being 2021’s Harmonics Of The Night. He had already put down a marker when still a member of The Police, recording a brace of instrumental albums in collaboration with Robert Fripp: 1982’s I Advanced Masked and 1984’s Bewitched.

In 2013 he formed another trio, Circa Zero, and with them recorded 2014’s one-off album Circus Hero. He also has six film scores to his name, and has written two books: his 2006 memoir One Train Later, and a 2021’s Fretted And Moaning, a collection of short stories.

Inevitably, he has never got close to eclipsing The Police. In 2003 the band were inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame. Four years later, on the evening of February 11, Summers, Sting and Copeland were reunited on stage as The Police, opening the 2007 Grammy Awards ceremony at the Staples Centre in LA.

That May, they launched The Police Reunion Tour with two shows in Vancouver, Canada. The tourran for more than a year and ended up being the third-highest-grossing of all time. On stage they sounded rejuvenated. The intangible alchemy going on between the three of them just as potent.

Yet by the time of the final show, at New York’s Madison Square Garden, they were also as far apart as ever. They haven’t played together since. In the intervening period from then to now, silence, except for the current re-release of The Police’s Greatest Hits on double vinyl. Better than anything, it’s this compilation that sums The Police up. Sixteen songs, the most recent 40 years old, but unforgettable and indelible still.

Pointedly, Miles Copeland wasn’t invited to return as The Police’s manager. How else had things changed between the 1980s and the reunion tour?

It was all kind of technical. Going back to the early days, I’d just turn up with my guitar and amp, and that was it. We were now in a whole different ball game. Stewart had a gigantic set-up. I had a complicated set-up, a very advanced pedal board and operated remotely off stage. Very slick. Sting had his thing going on. So each one of us had his guy, or guys, to oversee his own technical side. You could call it three different universes. But they all came together to create one thing. You couldn’t have done it any other way. It wasn’t the way we started, but it’s the way we ended up.

The reunion shows also emphasised how powerful the three of you are as a band. How difficult was it to once again let go of something that good?

If it was up to me I wouldn’t have let it go. It’s an interesting subject, and to do with fragility, frailty, ego and all that. I thought we could have gone on and played for years. We could have made some great new records. I don’t want to say too much more, because it’ll get too personal. It’s sad. We could have done more, but it wasn’t to be. One of the greatest bands of all-time got short shrift, I’m afraid to say.

All those songs aren’t about to be forgotten, though, are they?

That’s why it’s one of the greatest bands in history. The songs won’t go away. Every Breath You Take has passed one and a half billion plays on Spotify. It’s amazing when you consider the circumstances it was made in. I’ve just finished a fourth tour of Brazil with Call The Police (with whom he’s joined by two Brazilian musicians: bassist/singer Rodrigo Santos and Joao Barone on drums). We do all the Police hits and we’re really very good together. We were killing it every night of the tour. Mob scenes. You go: “Wow, how can this be?” It’s a very enjoyable thing to do once a year.

To come full circle and go back to your photographs. When you look at them, what do they tell you about yourself?

That at least I’ve got something to do when I’m out on the road. I’m not the sort of person who sits in his room and watches TV. As well as purely enjoying playing guitar, and being in a band, I have this other sub-set going on in my mind. I’ve a certain sort of energy I get from that. It shows me I’m alive. It keeps me alive. The act of creativity is all important to me. I feel as if I must be making something all the time. Not that I’m a nutter, or work-obsessed. Guitar, writing and photography. Those are the three things I do. That’s enough.

So what’s next?

I’m planning on making another record. I’ve never gone so long without doing one. Covid got in the way. I’m working on a TV series, too, about guitar riffs. I can’t say too much more about it at this point, but it’s going to happen in the next three or four months, I expect. I don’t want to stop. Having said that, I’m probably going to go off now and end up watching the fucking telly.

The Police’s Greatest Hits is out now via UPC. Summers’ exhibition Harmonics Of The Night/A Series Of Glances is the Leica Gallery, Munich, until July 15. Tickets for Andy Summers' summer tour of The US go on sale this week. For dates and details, visit his website.