Like a lot of prehistoric real-life monsters, the Megalodon shark was a cut above.

The extinct shark species, Otodus megalodon, is part of the extinct group of megatooth sharks. It's considered to be the largest shark (and fish) to have ever lived. Because of its size and apparent ferocity, it has also captured human imagination, with its legacy honored in pop culture, like the 2018 movie The Meg, in which Jason Statham battled the mighty creature.

While the sci-fi take on the Meg was undoubtedly 100 percent scientifically accurate, research still debate what this massive fish was really like — and how it stacked up against other sharks. Part of the reason why so little is known about this behemoth is that, despite its size, most of our information comes only from fossilized teeth.

In a new study, researchers used tooth and body size measurements from 13 species of living sharks to track the size distribution of lamniform sharks — which share ancestry with the Megalodon — over time.

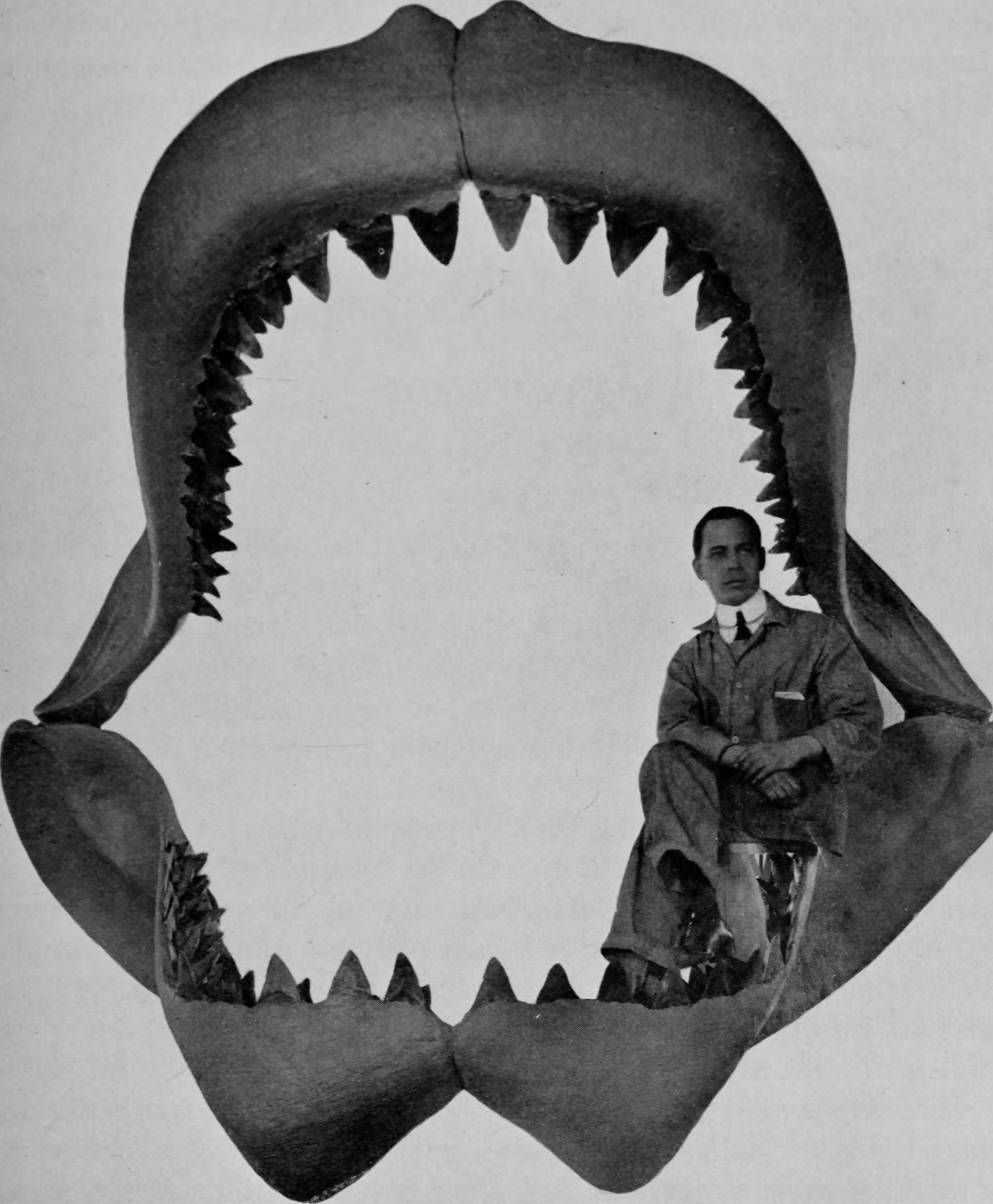

The researchers confirmed that, yes, the Megalodon, a word which simply means large teeth, was freaking huge. The shark measured as long as 50 feet. If you stood one up next to a telephone pole, the shark would tower over it.

But what is really impressive about the shark is how it measures up against its other shark relatives, explains lead study author Kenshu Shimada, a professor of paleobiology at DePaul University and research associate at the Sternberg Museum in Kansas.

"My research team did expect Megalodon to be gigantic based on my previous study," Shimada tells Inverse. "But what surprised us was actually seeing in our data a 7-meter gap [23-foot gap] between the size of Megalodon and the size of the next largest non-planktiviorous lamniforms not directly related to Megalodon in the entire geologic history."

The study is the first survey of living and extinct lamniform sharks across all lineages, and it "illuminates Megalodon to be uniquely gigantic relative to other sharks," Shimada says.

The finding was published Monday in the journal Historical Biology.

Correcting the record — The new research also helps to set the record straight, researchers say — both in science and pop culture.

While we can expect depictions like The Meg to be a bit theatrical, some scientific estimates of the shark's size have been "unnecessarily inflated," too, Shimada says. Anecdotal accounts have claimed the existence of a 59-foot Megalodon, for instance.

Shimada's team found evidence to suggest that's not possible. But don't let that detract from Megalodon's unique achievement among sharks.

"Although the scientifically justifiable maximum length estimates at present are in the range of 14.1-15.3 meters (46-50 feet) including the new study, it is still an impressively large shark," Shimada says.

He says the new research helps to understand ecology of the past — and perhaps the future.

"The fossil record is a window into the evolution of ecosystems, and understanding why species become extinct, and how their rise and demise affected their ecosystem is critical to today's oceans for issues like conservation of organisms, habitat preservation, and sustainable marine natural resources," Shimada says.

"Elucidating ecological variables as simple as the body size of organisms, especially carnivores like sharks in our new study, is the first step."

Abstract: Extinct lamniform sharks (Elasmobranchii: Lamniformes) are well represented in the late Mesozoic‒Cenozoic fossil record, yet their biology is poorly understood because they are mostly represented only by their teeth. Here, we present measurements taken from specimens of all 13 species of extant macrophagous lamniforms to generate functions that would allow estimations of body, jaw, and dentition lengths of extinct macrophagous lamniforms from their teeth. These quantitative functions enable us to examine the body size distribution of all known macrophagous lamniform genera over geologic time. Our study reveals that small body size is plesiomorphic for Lamniformes. There are four genera that included at least one member that reached >6 m during both the Mesozoic and Cenozoic, most of which are endothermic. The largest form of the genus Otodus, O. megalodon (‘megatooth shark’) that reached at least 14 m, is truly an outlier considering that all other known macrophagous lamniforms have a general size limit of 7 m. Endothermy has previously been proposed to be the evolutionary driver for gigantism in Lamniformes. However, we contend that ovoviviparous reproduction involving intrauterine cannibalism, a synapomorphy of Lamniformes, to be another possible driver for the evolution of endothermy achieved by certain lamniform taxa.