Abuja, Nigeria – The February 24 invasion of Ukraine by Russia has upset geopolitical and trade relations across the world, from matters of buying military equipment to increasingly expensive wheat and oil.

But for Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, there is an added dimension given its military relationships with all the major actors, especially Russia.

Historically, both countries have explored areas of defence cooperation and the arms trade. One of the side plots of the longrunning Cold War era was that during Nigeria’s 30-month-long civil war that ended in 1970, the Soviet Union extended military assistance.

Only last year, Abuja signed an agreement with Moscow for the supply of military equipment, personnel training and technology transfer.

The outcome of that deal has become increasingly visible since, given the acquisition and use of Russian-made combat and transport helicopters like the Mi-35M and Mi-171E, both export variants of the Russian Mi-24 and Mi-8, for military operations in Nigeria.

But since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the gains from the relationship may be eroding.

The West has responded to the crisis with a rollout of lethal military support, including anti-tank and surface-to-air missiles to NATO countries near Ukraine, like Poland. A barrage of sanctions has also been directed at individuals and entities in Russia. On March 24, the United States announced sanctions on multiple firms in Russia’s defence-industrial sector, some whose weapons are being used in the invasion.

The new sanctions and financial restrictions which align with previous actions and those taken by the European Union, United Kingdom and Canada, are designed to have a deep and long-lasting effect on the Russian defence sector.

They will prevent Russia’s access to cutting-edge technologies and inevitably disrupt supply chains and production, particularly for targeted defence companies such as Russian Helicopters JSC.

This, in turn, will affect their capacity to provide efficient maintenance support and additional aircraft to foreign customers, including the Nigerian Air Force.

The Nigerian military is currently wrestling with persistent domestic conflicts on multiple fronts including uprisings in the northeast by Boko Haram and the Islamic State West African Province (ISWAP), banditry in the northwest as well as increasingly violent separatist rebellions in the southeast.

It is also battling maritime piracy in the Gulf of Guinea, one of the world’s most dangerous shipping routes.

Without its Russian arms supply, Nigeria’s firepower will severely lag.

A punctured supply chain

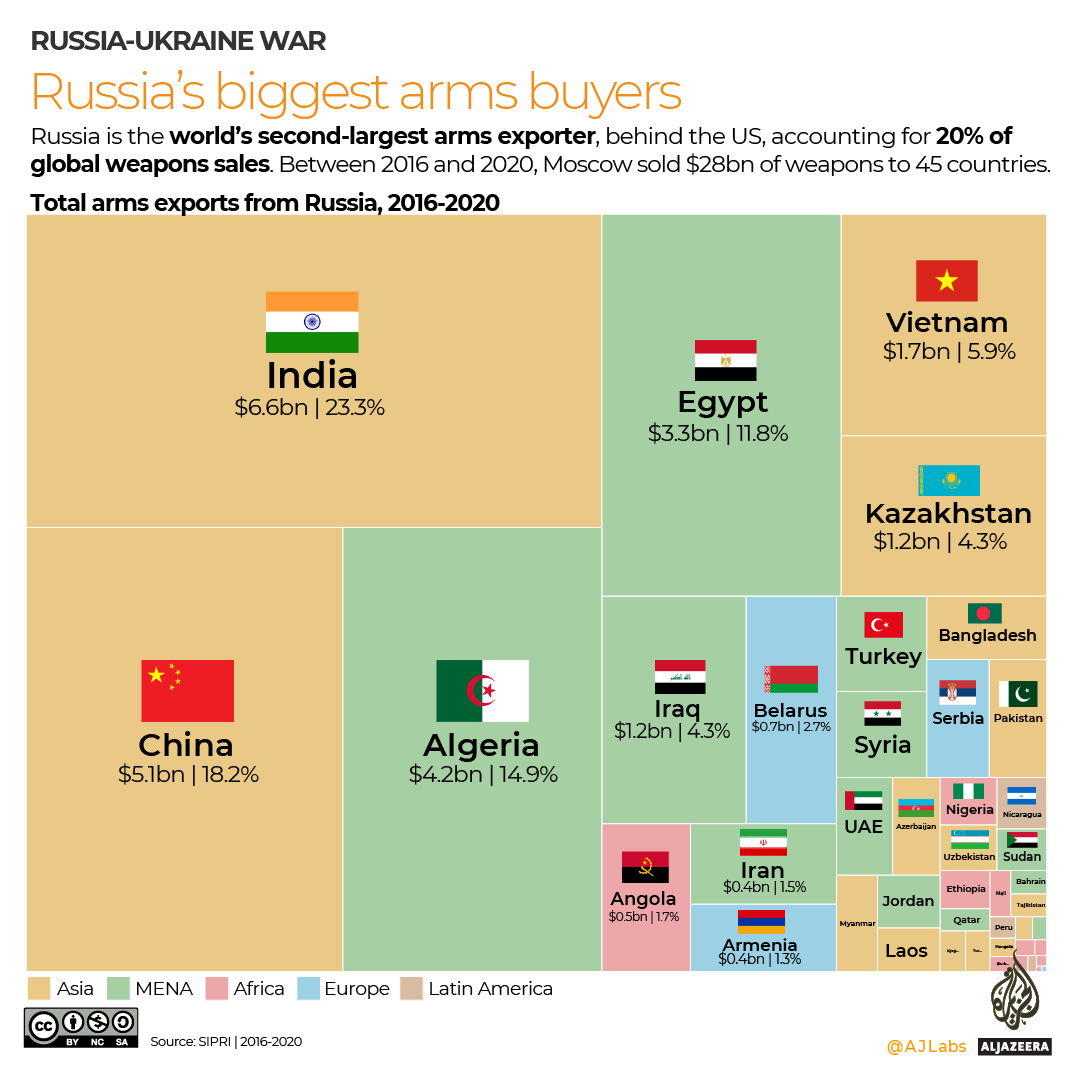

Russia is the world’s second-largest arms exporter, behind the US.

Between 2017 to 2021, it was notably the largest supplier to Africa, accounting for 44 percent of imports of major arms to the continent, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), which tracks the international arms trade.

Its 2021 report reveals that Nigeria received arms from 13 suppliers in the same five-year period, including 272 armoured vehicles from China, seven combat helicopters from Russia, three combat aircraft from Pakistan, and 12 light combat aircraft from Brazil through the US.

Over the past decade, Russian combat and transport rotary aircraft equipped with modern technological systems and sensors have become an integral element of Nigeria’s bid to expand its Air Force’s fighting capabilities.

But the delivery of more units of Mi-35M gunships suitable for close air support missions has already been marred by controversy. In 2019, the Nigerian ambassador to Russia hinted at a brick wall in the supply chain – a fallout from pre-existing sanctions.

Two years earlier, the US had signed the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) directed at puncturing the pipeline of arms exports after Russia’s annexation of Crimea, involvement in the Syrian civil war and meddling in the 2016 US presidential elections.

In its 2022 budget, the Nigerian government has made provisions for periodic depot maintenance and the upgrade of three older MI helicopters. The Mi-24V and Mi-35P variants are known to be used by the Air Force.

A few years ago, Russian Helicopters JSC launched upgrades for the Mi-35P variant including an improved target sight system, digital flight control system and night vision goggles.

Those would be perfect for Nigeria’s counterinsurgency operations against increasingly sophisticated armed groups within and around its borders. But the stream of new sanctions aimed at the Russian defence sector creates hurdles for Nigeria’s upgrade plans.

Belarus trained the AFSF

The sanctions are also extending to Russian ally Belarus which continues to provide support for Russia’s attack on Ukraine.

That support could endanger military cooperation between Nigeria and Belarus, which hosted the 2014 training of Nigeria’s elite tactical unit, the Armed Forces Special Forces (AFSF). The AFSF was formed as part of revamping the Nigerian military’s response to the escalating threat from Boko Haram.

There have been rumours of other planned deployments but nothing has been confirmed, except for a visit by the chief of one of Nigeria’s civil defence corps and top officials of the interior ministry to Minsk last August.

Ukrainian tanks, artillery and armoured personnel carriers

The war is also draining Ukraine’s military hardware manufacturing and export capacity and that could hurt Nigeria, too.

Between 2014 and 2015, Nigeria acquired military equipment from Ukraine including T-72 tanks, D-30 artillery, and BTR-4EN armoured personnel carriers before increasingly turning to China for assets.

New markets

All of that could push Abuja towards finding new markets for alternative helicopters able to carry out similar roles as effectively as its Russian ones, requiring new investments to build technical capacity and support infrastructure.

Still, there could be other political hurdles.

Last July, the US bipartisan Senate Foreign Relations Committee halted the proposed sale of 12 AH-1 Cobra attack helicopters and accompanying systems worth $875m to Nigeria, amid concerns about the government’s human rights record.

Nigeria’s information minister denied knowledge of the situation but his foreign affairs counterpart, Godfrey Onyeama, was more forthcoming. “We have a slight issue with some attack helicopters, but that’s more on the legislative side and not on the executive side,” said Onyeama during a meeting last year between US Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, and Nigerian officials in Abuja.

The short and long-term effects of the invasion of Ukraine and the continuous flow of sanctions provide new opportunities for collaborations with Nigeria, once reputed for its professional army standards and willingness to engage in international peacekeeping missions across Africa.

For now, that could also mean increased arms trade with China – the fifth-largest arms exporter globally – given the West’s reluctance, despite differences in quality, operationality and technical support.

In 2019, General Stephen Townsend, then a nominee for the position of commander, US Africa Command (AFRICOM), informed the US Senate Armed Services Committee that China provided Nigeria with armed unmanned aerial systems to improve its counterterrorism capabilities, but poor quality contributed to their infrequent use.

But the following year, Nigeria’s air force acquired a number of drones including the Chinese Wing Loong II drones which resemble the American MQ-9 Reaper drones. While the MQ-9 Reaper is reported to cost $30m, the Wing Loong II costs $1-2m.

These drones are known to lack the sophistication and technical capacity of their Western counterparts but without much of a choice, African countries could soon turn to them.

China’s relatively affordable and accessible military hardware could easily appeal to countries like Nigeria and states across the Sahel seeking alternative markets for assets acquisition.