The terrible tragedy of two deer hunters killed by a helicopter rotor blade

Johnny Cumming and my uncle Frank Erceg were the first fatalities in the venison export industry in New Zealand. At 10.20am on Tuesday, June 1, 1965, the two men were struck by the rotor blade of a Bell 47G-2 in the Mātukituki Valley west of Wānaka while dragging deer carcasses to the helicopter. They both died instantly.

The chopper was engaged in uplifting the deer carcasses from tussock-covered mountainous slopes, where it was almost impossible to rest in a secure level attitude with the rotor stopped. The pilot’s practice was to bring the helicopter down to ground level and place the forward portion of the aircraft’s landing skids firmly on the ground while maintaining sufficient revolutions per minute to keep the helicopter in a level attitude. One hunter would stand ready to load a deer carcass onto the left-hand litter, the other ready to load another carcass on the right-hand litter. Each man was required to act at the same time so that the weight of each carcass could be placed on the helicopter at an identical moment.

In this way, the lateral balance of the helicopter could be preserved and no undue control problem imposed upon the pilot.

Both Frank and Johnny had been briefed in this procedure by the pilot, Ray Wilson, and thoroughly understood the requirements. The system had worked well for the five days the two hunters had been shooting deer and working with Ray.

On the morning of the sixth day, Ray flew back to the identical spot where they had been loading before. He observed Johnny standing alone beside three carcasses while Frank was further up the slope. Positioning his helicopter, the pilot saw Johnny leave his position by a safe exit path and walk uphill apparently to assist Frank to bring another deer carcass down to the helicopter.

But when they returned dragging the carcasses, they somehow made fatal contact with the rotor blades, which due to the steep terrain were close to the ground in front.

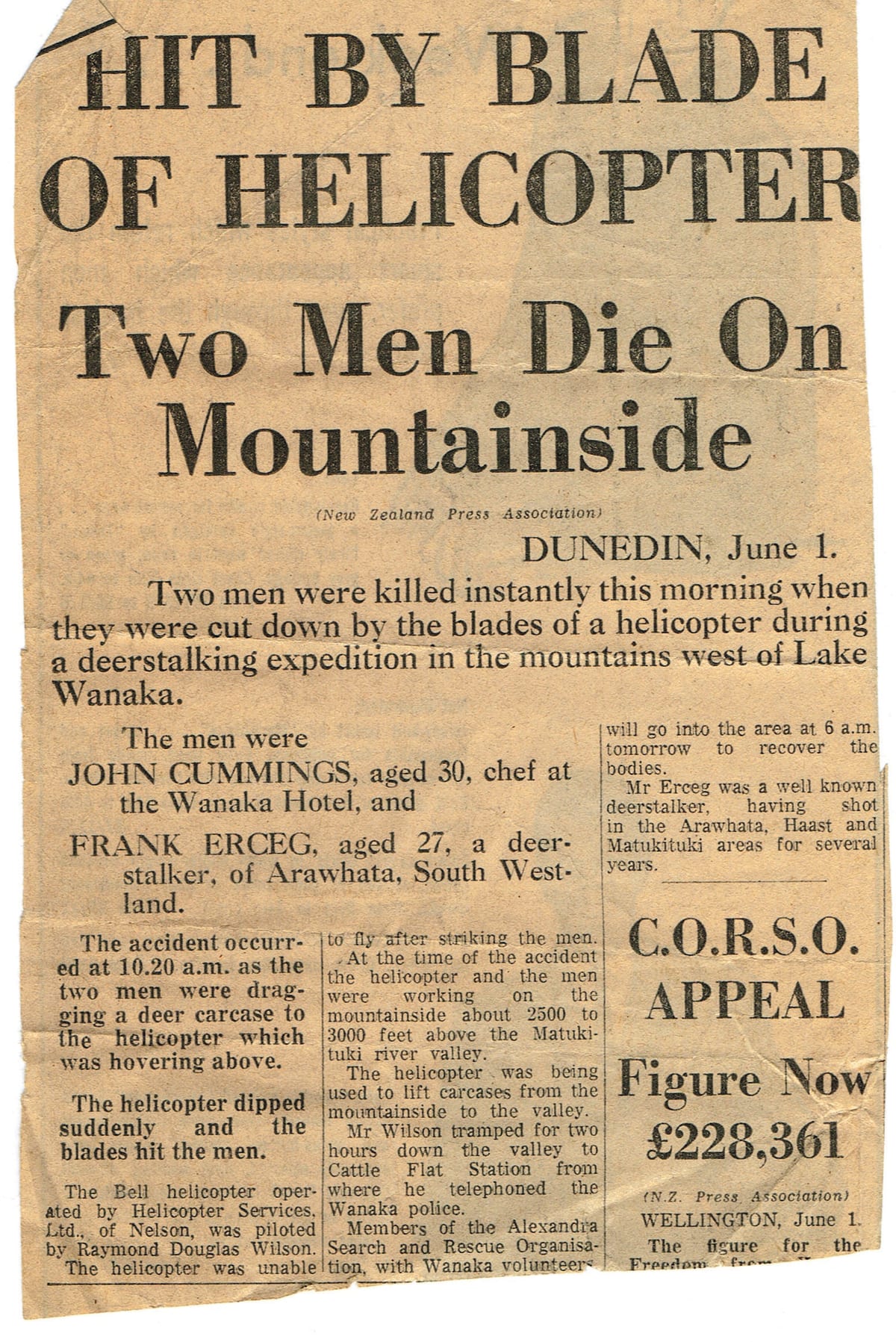

The Otago Daily Times reported, "It is understood the helicopter dipped suddenly and the blades hit the men." This "dip" is also stated in the Wanganui Chronicle on June 2. But no mention of this is recorded in the official Civil Aviation report. Weather conditions reportedly had no bearing on the accident. At the time of the occurrence, visibility was good in the vicinity of the helicopter, there was no wind, and the only cloud comprised light fog lying in patches on the valley floor below.

In 2016, I met with pilot Ray Wilson. He couldn’t offer anything more than the official report. As the only witness, I asked him, had the craft dipped suddenly, could this have happened? He was adamant that Frank and Johnny had walked into the blades. He sketched a diagram on some notepaper, explaining the steep angle of the mountainside and the proximity of the blades to the ground.

Ray landed the machine immediately as the slope wasn’t too steep, and cut the motor. He could see both men had been killed. The chopper had been rendered unserviceable and he had no other option than to take the long descent by foot down to the valley floor then on to Cattle Flat Station homestead and notify the police at Wānaka. At 12.10pm, two hours later, the call came into the police station.

The Mātukituki Valley deer recovery operation had been organised by Evan Meredith from Westland Frozen Products Ltd. Aside from Frank and Johnny, among the other contract shooters on the same campaign that week were Frank Woolf, Charlie Emerson and Vic Erceg. As soon as the tragic news reached Vic, he headed back to Makarora to be with his wife and to notify the family.

At the time of the accident, Johnny Cumming worked as a chef at the Wanaka Hotel. This was probably a few days off for him. He’d been previously employed by the NZFS so he no doubt enjoyed going up the mountains for a bit of shooting and adventure with his old hunting mates and earning some extra money.

Dave Osmers was Evan Meredith’s Makarora agent. Dave had been there also — working alongside Evan, coordinating the transport of the meat to the factories for processing. Dave was devastated to lose not one but two good friends on the same day. After this accident, Dave never worked with helicopters again on deer-recovery missions.

*

For many years, all I had relating to the day of the accident was some information from Frank Woolf, and the Aviation Report sent to me by Margaret Cochran.

I’d been hounding Mike Bennett for a few years about a photo published in his book The Venison Hunters, a black and white image of the recovery team on the hillside, with no credit to the photographer. Accounts were scant from the few people that were there, and I still had no other official documents, nothing from the police, or any information on the actual recovery of the bodies.

In November 2014 I had a phone call from Brian Farrow’s son Paul, of Paul’s Camera Shop in Christchurch. A customer had come in that morning with a CD and a bunch of photos to be printed. When Paul opened the disc, he instantly recognised some of the images. They were from the accident site and showed the recovery team alongside the helicopter. He had a contact number for me, from the guy who brought them in, Dennis McKay.

I contacted Dennis immediately. He said he was preparing images for Sir Tim Wallis’s 80th birthday celebration — that itself was interesting proximity to Frank and his story. On Dennis’s CD were his friend Bob Kilgour’s photos from the crash site.

The missing pieces were now fast falling into place. I got hold of Bob, who gave me the name of the guy who had headed the recovery team, Arnold Hubbard. He was still alive and living in Alexandra.

I couldn’t believe my luck. After years of having only one single black and white image in a book with no details, no leads, I now had four good-quality colour images as well as Arnold and his story of the recovery.

When I interviewed Arnold in 2014, he was 88. Yes, he said, he remembered the accident. Over the next hour, his story of the events surrounding the recovery unfolded. He had filed a report and taken photos. I was hopeful and asked whether he had kept copies of the report. Unfortunately, he’d thrown it out years ago along with the photos. He did suggest, though, some people to contact regarding other accounts or photos. Feeling dashed but still determined, I fired off emails in all directions and two weeks later received a reply with an attached copy of a very faded but legible coronial report. The folder included a one-page police report from a Constable Burgess from Wānaka, who had also been part of the recovery team.

With all this information, including the interview with Arnold, I was now able to map out a timeline of events following the tragic deaths of Johnny and my uncle Frank.

*

At 6am on June 2, the day following the double fatality, the recovery team parked their vehicles near Mill Creek on the river flats below the accident site. They reached the site almost 1200 metres up from the valley floor at 8.30am. There were 28 men in total including a representative from the NZ Police, Constable Burgess. Surprised that there were so many men, I asked Arnold why there weren’t more people in Bob’s photos.

He said, "They were held back until we had the bodies onto the Neil Robertson stretchers [bamboo and canvas, designed for vertical rescue and mountainous terrain]. It wasn’t a pretty sight considering how they died. There’d been a frost the night before; you can see it in the photos. The bubble on the helicopter iced over. The bodies had dropped and frozen, one still holding onto the hind legs of a deer."

Frank and Johnny were carried down off the mountain. It took some time. By late afternoon they reached the valley floor and transferred the bodies into the Land Rover and proceeded to the Wanaka Police Station. In the coroner’s report it was Vic who was called in to identify the body of his younger brother.

I asked Arnold about Bob Kilgour being there, taking photos and whether Bob was part of the official team. "No, he wasn’t, and I didn’t think it was appropriate him being there at all." Arnold continued in a stern tone: "Bob got wind of the accident and attached himself to the team. Arriving in his car around the same time, we all plugged up the hill quite steadily; Bob trailed behind us. I observed him taking photos from a prominent point near the accident site. This annoyed me as he wasn’t there in any official capacity; he was a freelance photographer and shouldn’t have been present."

Arnold himself had documented the scene on his 120 Voigtlander camera for his report. Bob Kilgour was simply doing his work as an independent photographer — and, consequently and remarkably, his images now remain as the only photographic documentation of the accident site and the first fatalities of the helicopter deer recovery era in New Zealand.

A mildly abbreviated version taken with kind permission from the new illustrated book Finding Frank: The Life of Frank Erceg – New Zealand Deer Hunter, Mountaineer, Photographer by Louise Maich (Bateman, $49.99), available in bookstores nationwide. It pieces together the life and times of the author's uncle, who built a log cabin on the edges of a river and hunted for meat in the magnificent Arawhata Valley in South Westland.