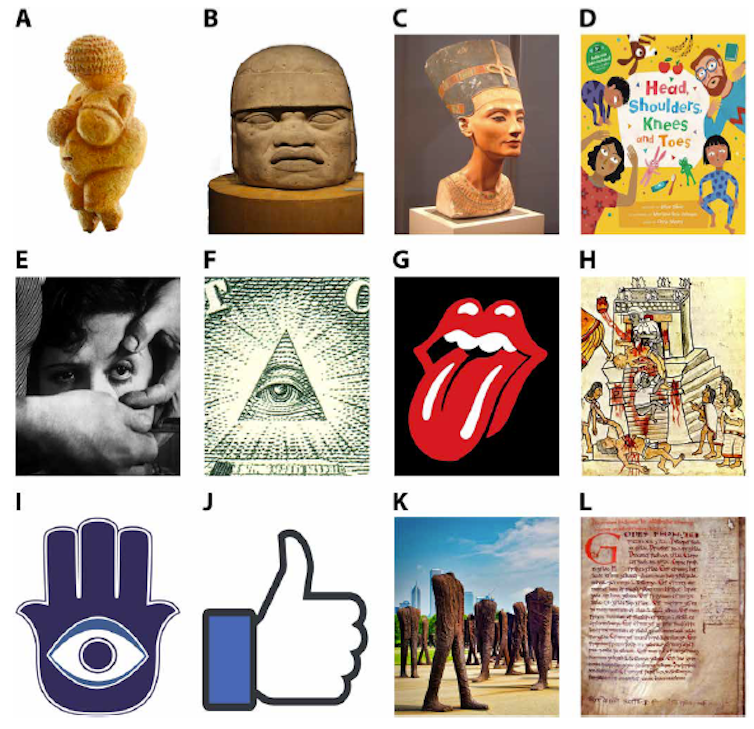

The Bible’s lex talionis – “Eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot” (Exodus 21:24-27) – has captured the human imagination for millennia. This idea of fairness has been a model for ensuring justice when bodily harm is inflicted.

Thanks to the work of linguists, historians, archaeologists and anthropologists, researchers know a lot about how different body parts are appraised in societies both small and large, from ancient times to the present day.

But where did such laws originate?

According to one school of thought, laws are cultural constructions – meaning they vary across cultures and historical periods, adapting to local customs and social practices. By this logic, laws about bodily damage would differ substantially between cultures.

Our new study explored a different possibility – that laws about bodily damage are rooted in something universal about human nature: shared intuitions about the value of body parts.

Do people across cultures and throughout history agree on which body parts are more or less valuable? Until now, no one had systematically tested whether body parts are valued similarly across space, time and levels of legal expertise – that is, among laypeople versus lawmakers.

We are psychologists who study evaluative processes and social interactions. In previous research, we have identified regularities in how people evaluate different wrongful actions, personal characteristics, friends and foods. The body is perhaps a person’s most valuable asset, and in this study we analyzed how people value its different parts. We investigated links between intuitions about the value of body parts and laws about bodily damage.

How critical is a body part or its function?

We began with a simple observation: Different body parts and functions have different effects on the odds that a person will survive and thrive. Life without a toe is a nuisance. But life without a head is impossible. Might people intuitively understand that different body parts are have different values?

Knowing the value of body parts gives you an edge. For example, if you or a loved one has suffered multiple injuries, you could treat the most valuable body part first, or allocate a greater share of limited resources to its treatment.

This knowledge could also play a role in negotiations when one person has injured another. When person A injures person B, B or B’s family can claim compensation from A or A’s family. This practice appears around the world: among the Mesopotamians, the Chinese during the Tang dynasty, the Enga of Papua New Guinea, the Nuer of Sudan, the Montenegrins and many others. The Anglo-Saxon word “wergild,” meaning “man price,” now designates in general the practice of paying for body parts.

But how much compensation is fair? Claiming too little leads to loss, while claiming too much risks retaliation. To walk the fine line between the two, victims would claim compensation in Goldilocks fashion: just right, based on the consensus value that victims, offenders and third parties in the community attach to the body part in question.

This Goldilocks principle is readily apparent in the exact proportionality of the lex talionis – “eye for eye, tooth for tooth.” Other legal codes dictate precise values of different body parts but do so in money or other goods. For example, the Code of Ur-Nammu, written 4,100 years ago in ancient Nippur, present-day Iraq, states that a man must pay 40 shekels of silver if he cuts off another man’s nose, but only 2 shekels if he knocks out another man’s tooth.

Testing the idea across cultures and time

If people have intuitive knowledge of the values of different body parts, might this knowledge underpin laws about bodily damage across cultures and historical eras?

To test this hypothesis, we conducted a study involving 614 people from the United States and India. The participants read descriptions of various body parts, such as “one arm,” “one foot,” “the nose,” “one eye” and “one molar tooth.” We chose these body parts because they were featured in legal codes from five different cultures and historical periods that we studied: the Law of Æthelberht from Kent, England, in 600 C.E., the Guta lag from Gotland, Sweden, in 1220 C.E., and modern workers’ compensation laws from the United States, South Korea and the United Arab Emirates.

Participants answered one question about each body part they were shown. We asked some how difficult it would be for them to function in daily life if they lost various body parts in an accident. Others we asked to imagine themselves as lawmakers and determine how much compensation an employee should receive if that person lost various body parts in a workplace accident. Still others we asked to estimate how angry another person would feel if the participant damaged various parts of the other’s body. While these questions differ, they all rely on assessing the value of different body parts.

To determine whether untutored intuitions underpin laws, we didn’t include people who had college training in medicine or law.

Then we analyzed whether the participants’ intuitions matched the compensations established by law.

Our findings were striking. The values placed on body parts by both laypeople and lawmakers were largely consistent. The more highly American laypeople tended to value a given body part, the more valuable this body part seemed also to Indian laypeople, to American, Korean and Emirati lawmakers, to King Æthelberht and to the authors of the Guta lag. For example, laypeople and lawmakers across cultures and over centuries generally agree that the index finger is more valuable than the ring finger, and that one eye is more valuable than one ear.

But do people value body parts accurately, in a way that corresponds with their actual functionality? There are some hints that, yes, they do. For example, laypeople and lawmakers regard the loss of a single part as less severe than the loss of multiples of that part. In addition, laypeople and lawmakers regard the loss of a part as less severe than the loss of the whole; the loss of a thumb is less severe than the loss of a hand, and the loss of a hand is less severe than the loss of an arm.

Additional evidence of accuracy can be gleaned from ancient laws. For example, linguist Lisi Oliver notes that in Barbarian Europe, “wounds that may cause permanent incapacitation or disability are fined higher than those which may eventually heal.”

Although people generally agree in valuing some body parts more than others, some sensible differences may arise. For instance, sight would be more important for someone making a living as a hunter than as a shaman. The local environment and culture might also play a role. For example, upper body strength could be particularly important in violent areas, where one needs to defend oneself against attacks. These differences remain to be investigated.

Morality and law, across time and space

Much of what counts as moral or immoral, legal or illegal, varies from place to place. Drinking alcohol, eating meat and cousin marriage, for example, have been variously condemned or favored in different times and places.

But recent research has also shown that, in some domains, there is much more moral and legal consensus about what is wrong, across cultures and even throughout the millennia. Wrongdoing – arson, theft, fraud, trespassing and disorderly conduct – appears to engender a morality and related laws that are similar across times and places. Laws about bodily damage also seem to fit into this category of moral or legal universals.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.