Dr. Michelle Thaller is perhaps the epitome of a hip NASA astronomer: An astrophysicist by background, Thaller emceed the 2022 broadcast that revealed the James Webb Space Telescope's first science images to the world. The decision to choose her was logical, as Thaller also regularly talks astronomy on The History Channel and Science Channel. As one NASA official told Salon, Thaller is "an expert science communicator."

"Now you see the underlying scaffolding of how the galaxy works."

Now that the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is celebrating the one-year anniversary of the release of its first science imagery, Salon spoke with Thaller about her favorite images.

The following interview has been lightly edited for length, clarity and context.

[laughs] It's interesting how you interpret these things! I'm a huge "Lord of the Rings" fan. I'm sitting here with Elvish tattoos that go up and down my arms. Yet [the Great Red Spot] as the eye of Sauron? That's one I hadn't heard before.

"This was losing sleep, staring at the ceiling in the middle of the night thinking, "Oh my God, how's this gonna work? Is it gonna work? Is this gonna be as successful as we hope?"

What do the tattoos say?

To tell you the truth, it's a little sad but also kind of beautiful. My husband died of cancer, and he wrote me a goodbye letter in Elvish. That's how geeky we are. And I was able to get a long tattoo that goes all over my body, and he was able to see it before he left. So that was nice. But that gives you a sense of the crossover here [at NASA].

Are you saying that on the Venn diagram of Lord of the Rings fans and NASA scientists, there is considerable overlap?

Absolutely, yes! Absolutely! In fact, if you got the two circles lined up, it would probably look a lot like they're the same. At any rate, the James Webb telescope for me has been in the family for decades. I have been friends with people that have designed it, that have worked on it. I am friends with the senior project scientist, Dr. John Mather, the Nobel Prize winner. And my husband worked on Webb for a long time as well. Seeing this whole thing come together — I mean, this was losing sleep, staring at the ceiling in the middle of the night thinking, "Oh my God, how's this gonna work? Is it gonna work? Is this gonna be as successful as we hope?"

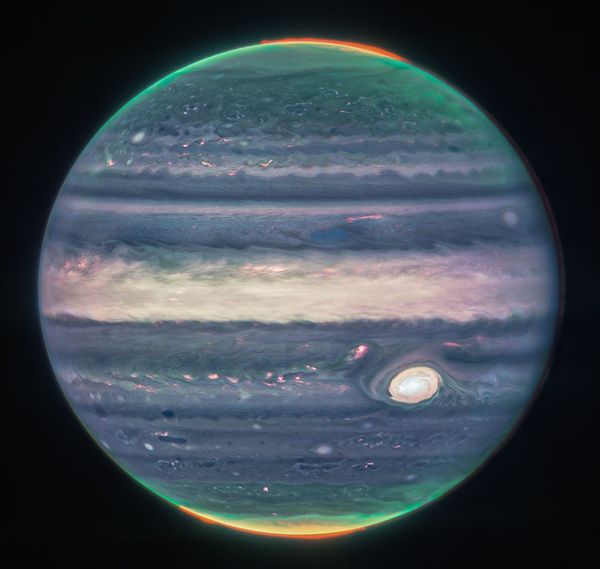

The Jupiter image, the one you're looking at, was one that I just was gobsmacked by. Visually speaking, you've got something like Jupiter, which is somewhere on the order of 400 billion miles away. You're taking pictures that are so clear. It's almost like you were at a spacecraft that was orbiting the planet. And you can see all of the different whirls and eddies in the atmosphere, and those are very important for us to study. There are whole teams of people here at Goddard [Space Flight Center] that study atmospheres of the giant planets.

And then, like you said, "the eye of Sauron," which isn't the way we usually look at the Great Red Spot of Jupiter, which is a big storm that's been going on for at least a couple hundred years. We don't really know. But normally you see it as a dark reddish color. The last few years it's been more of a sandy color, but here we're looking at it in heat light, in infrared light. And the storm clouds in this storm system are warmer than the surrounding clouds, and so the eye seems to be glowing. It's actually giving off more heat light than the rest of the clouds, and so it does turn into this glowing eye.

As you mentioned, Jupiter is gigantic. You could fit a thousand earths inside it, and it was most likely the first planet to form, or you'll get as large as something like a big giant planet in our solar system. You know, we're very interested in the composition of Jupiter because it sucked up all of this gas and dust around the Sun that was probably fairly old stuff, old hydrogen from not long after the Big Bang.

Jupiter is mysterious. It may be responsible for protecting the Earth from things like comets and asteroids that come our way. The gravity of Jupiter is much stronger than the Earths. That's the strongest thing that a comet sees falling into us, is Jupiter, which just sucks 'em up. This was visually stunning, this image, and that's what really got me.

I wish it were officially called the Phantom Galaxy! This is a galaxy that's about 32 million light-years away from us. Light that we see from it left the stars about 32 million years ago. This is another one that got me as far as visually what you're seeing. So I've always thought that it's easy to say the word galaxy. We all have heard that "a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away..." But galaxies, in fact, are monsters and people don't really understand how huge they are. The best way I can say it is that the Milky Way galaxy, the one that we live in, which is similar in size to this Phantom Galaxy. And the sun, which could fit a million earths inside it, right?

"The thing that blows my mind about these splotches is that I never thought I would be able to actually see an image of this."

If the sun could fit a million Earths inside itself, if the sun were the size of the dot of an eye on a page of text, a tiny little dot is the sun, then our galaxy would actually be that much larger than the Earth. And so these are incredibly vast clouds of stars, the only place in the universe where stars are forming, dying and creating the elements necessary to make life. In the Hubble image of the Phantom Galaxy — this press release had had images both from Hubble and from Webb — in the Hubble image, you see the visible light depiction of the galaxy. It's all of these beautiful glowing stars. And the stars kind of blast out everything else.

The center of the galaxy is just a big cloud made of billions of individual stars. Stars are bright. And then you notice there's a little bit of dark schmutzy material. The disc of this galaxy is about one hundred thousand light-years across. So you're talking, with thousands of light-years of this dark, dusty material, that's really where all the action is when it comes to us. That dark dusty material is debris from dead stars that blew up. And the dust that astronomers call anything that's not a gas — hydrogen, helium, you know — the dust has the carbon that makes up organic molecules. It has things like phosphorus [a building block for life], in our DNA, and the calcium in our bones, and the iron that makes our blood red.

The only way the universe makes this stuff is when those stars blow up and create that dust, and then that dust enriches areas all around the galaxy. New stars form, new planets form and here we are. And the thing that's amazing is if you go to the Webb image, as opposed to the Hubble, the Webb image shows the galaxy again in infrared light and heat light. And certainly stars give off lots and lots of heat, but they become less dominant [over time].

Stars are relatively small objects compared to a galaxy. And these giant clouds of dust start to glow themselves. They actually have some warmth to them. And in real life, they're very cold. They're actually probably only 10 to 20 degrees above absolute zero. But even so, that's enough for some heat to be detected by Webb. And now you see the underlying scaffolding of how the galaxy works.

Really, this is the exact opposite. I know it's a splotch. It's a little out-of-focus splotchy thing. But the reason these things look like splotches is they are unbelievably far away. These are some of the farthest objects we've ever seen. By far away in terms of the Webb telescope, we're talking something on the order of 13 billion years of light travel time. We're looking at objects where the light that's coming to us now had to travel through space for such a huge distance that we're looking at the universe as it was 13 billion years ago. The Big Bang was only about 13.8 billion years ago. So we're looking back to the very, very early youngest galaxies here.

The thing that blows my mind about these splotches is that I never thought I would be able to actually see an image of this, when I was in astronomy grad school and we were learning about what happened in the very earliest part of the universe.

Read more

on astronomy