As a woman in my 30s who was constantly typing “ADHD” into my computer, I had something interesting happen to me in 2021. I started receiving a wave of advertisements beckoning me to get online help for ADHD, or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. One was a free, one-minute assessment to find out if I had the disorder, and another was an offer for a digital game that could help “rewire” my brain. Yet another ad asked me if I was “delivering” but still not moving up at work.

The reason the term ADHD litters my digital life is that I am a clinical psychologist who exclusively treats patients with ADHD. I’m also a psychiatric researcher at the University of Washington School of Medicine who studies ADHD trends across the lifespan.

But these advertisements were a striking new trend.

The following year, in October 2022, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced a nationwide shortage of mixed amphetamine salts, a drug that is marketed as Adderall. The brand name Adderall and its generic counterparts have become one of the most common medication treatments for ADHD. Over the next several months, additional ADHD medications joined Adderall on the list of prescription drugs in short supply.

As of August 2023, the U.S. is still experiencing a shortage of several ADHD medications, with some not expected to be resolved for at least a few more months.

The shortage appears to have been triggered by a combination of high demand and access to key ingredients. In recent months, millions of Americans have found themselves with no guarantee of access to their daily medications.

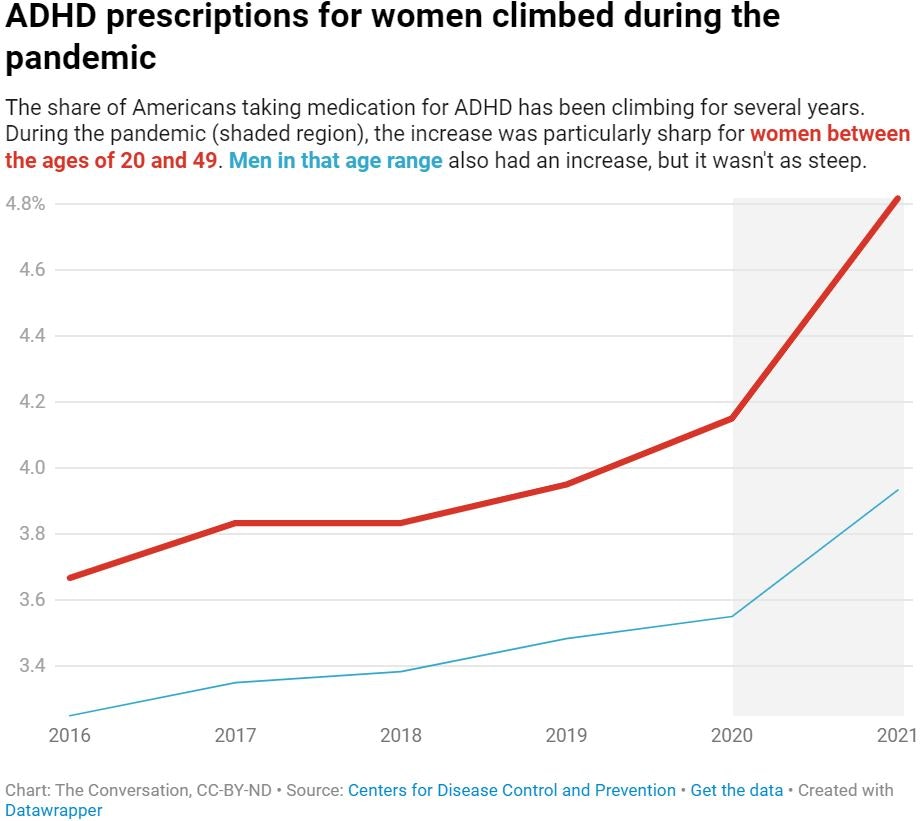

In March 2023, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported an unprecedented spike in stimulant prescriptions between 2020 and 2021. Perhaps most surprising was that the demographic showing the greatest increases in stimulant use — an increase of almost 20 percent in one year — were women in their 20s and 30s.

The CDC’s findings, along with the stimulant shortage, raise some interesting — and still unanswered — questions about what factors are driving these trends.

The challenge of diagnosing adult ADHD

Despite the growth in awareness of ADHD over the past couple of decades, many people with ADHD, particularly women and people of color, go undiagnosed in childhood.

But unlike depression or anxiety, ADHD is quite complicated to diagnose in adults.

Diagnosing ADHD in either kids or adults first involves establishing that ADHD-like traits, which exist on a continuum and can fluctuate, are severe and chronic enough to prevent a person from living a normal, healthy life.

The average person has a couple of symptoms of ADHD, so it can be hard to draw the line between ADHD-like tendencies — such as a tendency to lose keys, having a messy desk, or often finding your mind wandering during a dull task — and a diagnosable medical disorder. There is no objective test to diagnose ADHD, so doctors typically conduct a structured patient interview, ask family members to fill out rating scales, and review official records to come up with an actual diagnosis.

Diagnostic challenges can also arise for psychiatrists and other health care practitioners because ADHD shares features with many other conditions. In fact, difficulty concentrating is the second most common symptom across all psychiatric disorders.

Further complicating things, ADHD is also a risk factor for many of the conditions that it resembles. For example, years of negative feedback may lead some adults with ADHD to develop secondary depression and anxiety. Zeroing in on the correct diagnosis requires a well-trained clinician who is able to take enough time to thoroughly gather the necessary patient history.

The stress of the Covid-19 pandemic

Looking back, some clear factors have been at play, but it remains unclear the degree to which they are driving the spike in stimulant prescriptions.

In 2021, the U.S. was still deep in the acute phase of the Covid-19 pandemic. People were still losing jobs, facing financial strains, and juggling work-from-home challenges such as having children at home doing online schooling. Many families were losing loved ones, and there was a huge sense of uncertainty over when normal life would return.

The demands of the pandemic took a toll on everyone, but research shows that women may have been disproportionately affected. This may have led to a greater proportion of adults seeking stimulant treatments to help them keep up with the demands of daily life.

In addition, without access to in-person recreational spaces, the pandemic increasingly drove many people to spend more time on digital media.

In 2021, a social justice movement focused on “neurodiversity” was gaining momentum online. Neurodiversity is a nonmedical term that refers to the wide diversity of brain processes that diverge from what has traditionally been considered “typical.” At this moment, #ADHD became the seventh most popular health topic on TikTok. Relatable anecdotes of missing keys, procrastination, romantic mishaps, and secret signs of ADHD began to flood the internet.

But while the internet exploded with ADHD content, researchers in Canada began sorting #ADHD TikTok videos into categories based on their accuracy and helpfulness. They reported something important: A majority of #ADHD content was misleading. Only 21 percent of the posts provided useful and accurate information.

So, amid the growing online community of newly self-diagnosed people with ADHD, many probably did not actually have the condition. For some, cyberchondria — or health-focused anxiety after online searching — may have been creeping in. Others may have mistaken ADHD for another condition, which is surprisingly easy to do. Still, others may have had mild attentional issues that do not rise to the severity of ADHD.

What ADHD care looked like in 2021

In 2021, the U.S. mental health system was overloaded. Most traditional ADHD providers, such as psychiatrists, psychologists, mental health therapists, and psychiatric nurse practitioners, had months-long wait lists for new patients. People who were newly seeking help for ADHD found faster appointments with their primary care providers, who may or may not be comfortable diagnosing and treating adult ADHD. Since demand for ADHD care exceeded capacity, new options were needed to meet patient needs.

Around that time, online ADHD care startups began to pop up, reaching prospective consumers with appealing digital ads like the ones I received.

Compared with traditional care, the startup models were reportedly using cost-cutting methods, such as favoring quick assessments and a low-cost workforce. The startups were also reported to be relying on a uniform care model that did not adequately personalize treatments, often prescribing stimulants over treatments that may have been better indicated.

Some of these companies are now under investigation by the federal government.

Although they were controversial in the medical community, these models may also have reduced barriers to ADHD care for many people.

The verdict is still out

Until the CDC releases its 2022 and 2023 stimulant prescription data, researchers like me will not know whether the 2021 trends of increased prescribing to adults and high demand for ADHD medications will continue.

If the trends stabilize, it may mean that patients who have been unable to access care may finally be getting the help they need.

If ADHD prescribing returns to pre-pandemic levels, we may learn that a perfect storm of Covid-19-related factors caused a momentary blip in people seeking ADHD treatment.

What is clear is that the current shortage of mental health care workers who feel comfortable diagnosing and treating ADHD in adults will continue to affect the ability of new patients to get proper diagnostic evaluations for ADHD.

This article was originally published on The Conversation by Margaret Sibley at the University of Washington. Read the original article here.