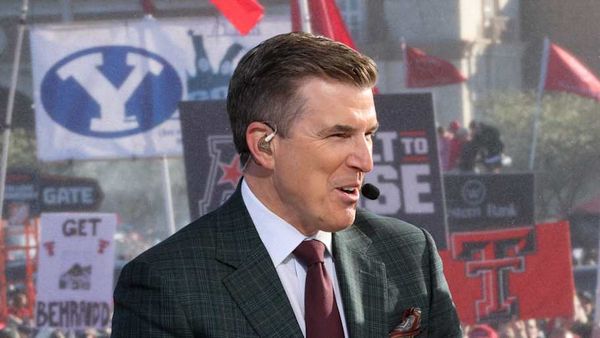

Almost every review to date mentions the brutal argument that closes the first section of Eleanor Catton’s Birnam Wood. In a novel filled with incident – disasters, chases, one very bad acid trip, general maleficence – it is telling that this scene lingers.

The members of the titular Christchurch guerrilla gardening collective have gathered for a hui (meeting) to discuss a proposed partnership with surveillance technology mogul Robert Lemoine, one of the American billionaire survivalists buying up land in New Zealand. This is bitterly opposed by a former member, Tony, who sees it as accepting “blood money”. But Mira, their nominal leader, argues that the partnership may be their only hope for survival:

there comes a point where refusing to compromise means choosing to be ineffectual and how is that not a violation of our principles? Isn’t that worse – to throw away everything we’ve done, all our hard work, just for the sake of being able to tell ourselves we were right?

Review: Birnam Wood – Eleanor Catton (Granta).

The argument goes on for pages, painfully familiar and utterly compelling. At what point does compromise become complicity? What use is ideological purity if it results in irrelevance? These are difficult questions. We know there are no easy answers.

It therefore comes as something of a surprise when Birnam Wood is repeatedly willing to provide them. The novel makes it unambiguously clear, at almost every interval, that Lemoine will taint and destroy everything he touches. So why do people keep extending him their hand?

Set in 2017, Birnam Wood begins with a landslide which kills five people and blocks the (fictional) Korowai Pass in the South Island of New Zealand, cutting off a large farm owned by pest-control magnate Sir Owen Darvish and his wife Jill. The unused farmland has attracted Mira’s attention as a potential site for one of Birnam Wood’s covert plantings.

While inspecting the property, Mira encounters Lemoine, who is purchasing it to build an apocalypse-proof super-bunker. He subsequently offers to fund the gardening collective, partially because he is intrigued by Mira, but also as a cover for his more nefarious activities in New Zealand.

Lemoine pretends to be an “ordinary” billionaire:

a far-sighted, short-selling, risk-embracing kleptocrat, an incarnation of unapologetic zero-sum self-interest, a radical misfit, a “builder” in the Randian sense, a genius, a tyrant, a status-symbol survivalist hedging his bets against any number of potential global catastrophes …

The reality is far worse. Lemoine is overseeing an extensive illegal mining operation in the Korowai National Park. The lethal landslide that sets the plot in motion was the result of his activities. Adept at turning disaster into opportunity, he has decided to purchase the Darvishes’ isolated property and use the construction of a bunker to conceal the extraction of his payload.

This is an audacious reversal and you should envy the reader who got bored at the second paragraph of my review and clicked away before reaching this early spoiler. It is, however, only the very beginning of the novel. Birnam Wood is just getting started.

Read more: Ghoulishness, depravity and stupidity: welcome to the world of Ottessa Moshfegh's Lapvona

Dramatic escalations

The Birnam Wood collective is a brilliant creation, positioned right on the cusp between believable and absurd. Its aim is to raise awareness of the sustainable potential of unused land by planting crops in gardens and backyards, then selling the produce, with the landholders getting a cut of the proceeds. True to its activist roots, however, Birnam Wood still engages in illegal plantings on private lands, without the knowledge or consent of owners.

Founded by Mira during her idealistic university days, the collective is undergoing an identity crisis when the novel begins. The energy and commitment of its membership is waning and the rise of the “innovation economy” offers the tempting prospect of a lucrative realignment.

A new vocabulary had come into force: Birnam Wood was now a start-up, a pop-up, the brainchild of “creatives”; it was organic, it was local; it was a bit like Uber; it was a bit like Airbnb.

Limping and exhausted, sustained only by good intentions and fraying friendships, Birnam Wood is primed for Lemoine’s transformative attention. This unlikely alliance leads to a series of in increasingly dramatic escalations.

Catton’s scenario, while inventive, may also seem implausible. Writing in the New Zealand Listener, Charlotte Grimshaw noted that a reader “might find something slightly Monty Python in the idea of guerrilla gardening”. Steve Braunias, writing in Newsroom, found Birnam Wood’s plot too convoluted to take entirely seriously.

But the novel is quite self-aware. Many of the New Zealand characters are directly struggling with this perceived implausibility themselves. Their own failure to suspend their disbelief leaves them vulnerable to Lemoine’s schemes. They accept his lies because the alternatives are too outlandish to contemplate. One character has a chance encounter with an armed mercenary near Lemoine’s mining site, but almost immediately dismisses it: “This was New Zealand for heaven’s sake. People didn’t carry guns.”

Their certainty is almost comical, but coming in 2017, just two years before the horrific Christchurch Mosque shooting, it sits uneasily.

Catton has stated that Birnam Wood aims to critique New Zealand’s complacency about corruption and environmental matters, and its tendency to coast on an increasingly dubious clean and green reputation. This attitude is exemplified by the refusal of many of its characters to fully believe that terrible things could happen in their country, or to them specifically. The events around them feel untrue to their register of reality.

In his 2016 essay collection The Great Derangement, Amitav Ghosh argues that traditional approaches to plausibility in literary fiction are now out of kilter with the global environmental crisis. Within the conventions of literary realism, sudden shifts and dramatic upheavals often seem implausible. According to Ghosh, this attitude now obstructs our awareness of the scale and frequency of the disasters rolling up to our door.

Birnam Wood’s fast-paced narrative drama may seem larger than life, but it reveals clear lines of cause and effect, consequence and culpability. Change is not coming gradually for its characters. The ground is shifting beneath their feet.

As a thriller, Birnam Wood has been compared to Lee Child’s works, but it also shares similarities with Mick Herron’s Slough House series, where suspense and comedy arise from the protagonists’ failure to fully grasp the rules or genre of the narrative they are trapped within. Like the floating narrator in Herron’s novels, Catton provides an arch commentary on each of her characters, exposing their limitations and internal contradictions.

Mira might seem like a familiar archetype – a confident, charismatic activist – but her conflicting motives reveal layers to her personality. She begins the novel deeply afraid of losing her close friend Shelley because she depends on Shelley’s administrative skills, but also because the quiet, detail-oriented Shelley provides a point of contrast that is important to her self-definition. She is belligerent in her interactions with Lemoine because she rightly mistrusts him, but also because she hopes that her combative attitude will keep him interested.

Tony, who denounces Lemoine at the hui, is a would-be journalist determined to investigate the billionaire’s activities in Korowai. But he is motivated in no small part by anger at Mira (his former lover), a desire for fame, and a lingering sense of resentment from being “cancelled” as a travel writer for his cultural insensitivity. He is doing the right thing for an amalgam of good and bad reasons.

Even the Darvishes reveal some enjoyable contradictions. Like all good New Zealanders, they are desperate to demonstrate how little their success matters to them, but become mildly aggrieved when it goes unrecognised by others.

Read more: Macbeth by William Shakespeare: a timeless exploration of violence and treachery

Mephistopheles in a tracksuit

Catton has said her approach to characterisation in Birnam Wood was informed by Macbeth, with each character having the potential to be seen as a Macbeth-like figure. Their trajectories all see them tempted into some form of ambitious overreach, often involving a betrayal of some kind, whether of friendship, principle, or their own better judgement. And they are eventually ensnared by seemingly impossible outcomes. Birnam Wood is marching for them all.

Among this cast of multifaceted characters, Lemoine presents something of a conundrum. He is Mephistopheles in a tracksuit, a master of the Xanatos Gambit, often eight steps ahead of everyone else.

Again, we come back to the question of plausibility in Birnam Wood. Is Lemoine a convincing antagonist? Rachael King sees him as a malevolent, anti-Jack Reacher figure, relentless and almost impossible to overcome. Braunias finds his evil nature too simplistic and “OTT”. Grimshaw struggles to accept that someone as capable as Lemoine would even deal with Birnam Wood in the first place.

This is a fair criticism, given that his support for the collective’s activities present him with enormous risks for unclear rewards. I kept waiting for a deeper motivation or genuine vulnerability that would better explain his interest in the guerrilla gardeners, but this contradiction is never satisfyingly resolved.

There is also something a little dated – perhaps very 2017 – in a representative of the tech-mogul overlord class being characterised as this ultra-rational, ruthlessly effective Machiavellian schemer. Compared to the petulant, blundering, sticky-fingered child kings who so effortlessly dominate our world and newsfeeds, Lemoine comes across rather favourably. At least this guy is competent. At least he puts some thought into being evil.

But perhaps Lemoine is better understood as a malign force than as a fully realised character. Catton has described her growing unease with the rise of online tracking and surveillance technology. She finds something “psychopathic” in the way algorithms now permeate our lives and interactions, anticipating our desires, covertly monetising our behaviour.

This can be linked to the cold-blooded movements of her antagonist. There is something algorithmic in Lemoine’s slippery readjustments, his greedy pursuit of data, and the dark inevitabilities that result from his calculations.

Steve Brauinas compares Lemoine to straightforward monsters like Freddy Kruger and Michael Myers, but Count Dracula might provide a better point of reference. Alongside the nods to Macbeth, there are some striking parallels between Birnam Wood and Bram Stoker’s novel. Both begin with seemingly innocuous real estate deals, which bring a distant, otherworldly evil frighteningly close to home. Both focus on the attempts of an enigmatically powerful foreign investor to control and corrupt two young women, with one proving more susceptible than the other. Also like the Count, Lemoine is most powerful at night, when the infra-red cameras of his drone army are more alert to intruders.

Bram Stoker’s novel emerged from the techno-optimism of the late 19th century. It begins as a gothic horror, but gradually evolves into a rip-snorting thriller as its protagonists use modern science and technology (Telegrams! Phonographs! Steam engines! Blood transfusions!) to resist the Count.

Catton offers a contemporary pessimism. Technology empowers the predator, not the prey. Privacy is penetrated. Data is drained. Movement and communication become perilous. Birnam Wood begins as a thriller, but by its ending it becomes, if not quite gothic, then some other kind of horror.

At its core, Birnam Wood is concerned with how its New Zealand characters respond to Lemoine’s corrupting influence. None of them harbour any real illusions about his true nature. “They’d known he was bad right from the start.”

Nonetheless, they allow themselves to be seduced. Early in the novel, Lemoine confesses to Mira about how “easy” it is to succeed as a member of the wealthy global elite. He doesn’t have to put much effort into his deceit and manipulations. The other characters are more than willing to do all the hard work for him. We follow their increasingly desperate attempts to find ambiguity, nuance and shades of grey in a situation which is – “implausibly” – black and white.

Birnam Wood is a novel of depth and complexity, but it is also refreshingly unsubtle. The right course of action is clear from the outset. Never invite the vampire into your home.

I attended Burnside High School in Christchurch at the same time as Eleanor Catton's older siblings. Her father was a colleague of my parents at the University of Canterbury, and one of my lecturers at the same institution.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.