When Geddy Lee was writing his autobiography, he thought of giving it the title My Life In Comedy. His publisher, however, felt that was a little too self-deprecating for the memoir of a man famed for his virtuoso skills as multitasking bassist, singer and keyboard player with legendary rock group Rush. So Lee proposed an alternative title, again with tongue in cheek, and this one stuck: My Effin’ Life.

“I do have a tendency to drop ‘F’ bombs during any conversation,” he explains, “so effin’ is a word I use a lot.” Lee is talking to Classic Rock on a beautiful end-of-summer day in London, where he is on holiday with his wife Nancy. Dressed all in black, his long hair pulled back, and peering from behind tinted glasses, he’s looking good for a man who recently celebrated his seventieth birthday. He’s also in relaxed mood as he begins with some small talk about baseball and his grandchildren. But within the first few minutes of an hour-long conversation, his mood suddenly shifts as he reveals the reason for putting his extraordinary life story on record.

“Originally I had no interest in writing a memoir,” he says. “I just felt like my life is unfinished. But a couple of things happened that profoundly changed my point of view.”

In January 2020, Neil Peart, Rush’s drummer and lyricist, died at the age of 67. The following year, Lee’s mother Mary, a Holocaust survivor, passed away aged 95.

“I had the sadness of watching my mother slowly being affected by the ravages of dementia,” Lee says. “It was heartbreaking to see that she could no longer remember stories she had told me in the past. And she didn’t know who I was at times, which freaked me out. So it got me thinking about memory and how fragile our memory banks actually are.

"The other thing was that Neil had finally succumbed after a three-and-a-half-year battle with brain cancer, glioblastoma, and during that time I witnessed kind of the same things I’d seen happen to my mother. Neil had a remarkable memory right up until the end, don’t get me wrong. Sometimes his powers of recall were staggeringly accurate even when he was suffering the most. But, you know, I started thinking: ‘What if I forget? Holy crap, what if all the experiences of my life suddenly disappear into the dust?’”

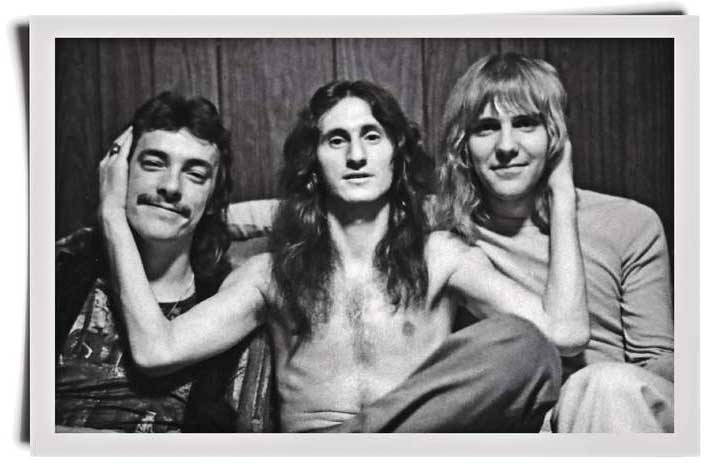

There are plenty of good memories in My Effin’ Life, mostly relating to all the great music Lee made with Rush, and all the high times shared over 40 years with Neil Peart and guitarist Alex Lifeson. But in the course of this interview, when Lee recalls the hard times and the losses, there are moments when he takes lengthy pauses as he struggles to find the right words and to keep his emotions in check.

There is a remarkable degree of raw honesty and self-awareness in My Effin’ Life. As Lee puts it: “What is the point of a memoir, other than to give you some sort of explanation into the human that’s writing it?”

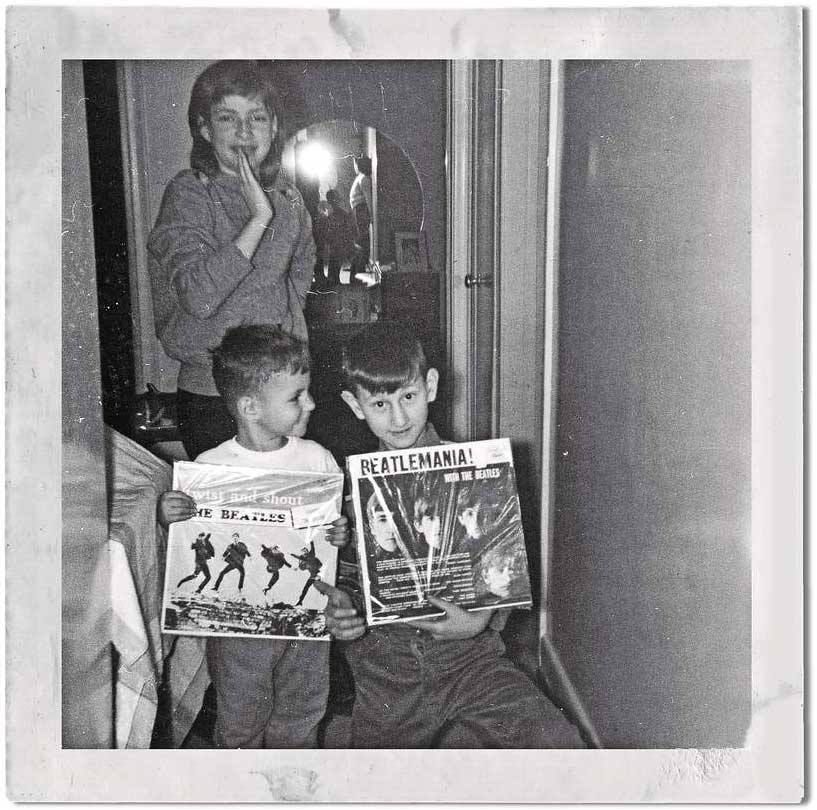

In the early part of the book you trace the history of your parents and the horrors they experienced as Polish Jews in Nazi concentration camps. Was that a way of honouring your mother, who first told you those stories when you were a child?

That’s true. I am trying to honour her. In 1995, when I took my mother back to Germany with my brother and my sister, I recorded what she said for a family history. Future generations need to know what happened, and I wanted to tell the right story. I wanted to check the facts and find out exactly what happened as best as I could, and that was a pretty deep dive. So I began to cross-reference what I had on tape from her with other stories from family members. I got down to what I think is the most accurate telling of what they lived through. And I felt it essential for my own story not only to honour my mother, but to explain.

You also write with a degree of humour about what it is to be Jewish. At times it reads a little like Woody Allen.

Absolutely! Humour was a big part of how these survivors dealt with what they’d witnessed. I like to think that the culture I was born into wasn’t just based on religion. It was a culture about attitude and humour and brown food and overcooked meats. There’s a lot to make fun of, and a lot of joy I get from being a part of that culture. I’m an atheist, I don’t believe in God, but I do love being a Jew for all those reasons.

You’re able to laugh at yourself. For example when you’re remembering The Fountain Of Lamneth, one of the more pretentious early Rush tracks.

Well, back then, in the heat of the moment, The Fountain Of Lamneth seemed like a good idea. This was our first twenty-minute conceptual track, and we were deadly serious about it. But you also have to bear in mind that we were pretty fucking high when we were making it.

On the subject of drugs, there’s a rather sad story from the early eighties where you hung out with a female fan who had some cocaine, but abruptly dispensed with her company as soon as the last line had been snorted.

It was really a low point in my life, I have to be honest. I remember it so clearly – going back to my hotel room and looking at myself in the mirror, thinking: “What the fuck is wrong with you?” You can try blaming it on the drug, but it’s you taking the drug. I realised what I had allowed myself to turn into, and it shocked the hell out of me. That moment was the end for me with cocaine. I guess you could call it a cautionary tale.

You also admit that the rock’n’roll lifestyle – all the long months on tour and in recording studios – put a strain on your relationship with your wife, Nancy. Did you consult her about making this public in the book?

I felt that I had to write the full story – this is who I am, and how I lived. If there’s no room for that in a memoir, then really you’re just kind of telling tales. Nancy still hasn’t read the book. She’s a very reserved person, so when she finally reads it in full I’ll be very curious to see how she reacts to me.

You write very movingly about the tragic events of the late nineties, when Neil Peart suffered the losses of his daughter Selena in a road accident and his wife Jacqueline to cancer. But in later years, after Neil had found happiness again with his second wife, Carrie, and their daughter Olivia, he insisted on shorter tours with Rush to allow more time with his family. It was a choice you understood, but still resented?

Well, one part of your head is saying that Neil deserves his time with his new family. Look what he’s been through. He’s had the shit kicked out of his life, and he still walks around with demons from that terrible time. You never heal from that. You learn to cope, but you never fully recover. So who the fuck am I to deny him that opportunity? You got that on the one hand.

On the other hand you’re going: “Fuck, man, this show is so great! I want to take it to more people. Just ten more gigs, mate…” But you take the good with the bad. And honestly, I didn’t think he’d ever come back after he lost Jackie and Selena, but he did. So everything since then really was bonus time, from 2001 all the way to 2015.

The R40 tour turned out to be Rush’s last, ending at the LA Forum on August 1, 2015 after just thirty-five dates. What was your state of mind at that time?

I was frustrated. I had some anger. And then, a year later, Neil sent an email where he announced he was sick. And in a heartbeat, all that resentment and frustration was gone.

Because Neil had always been so protective of his private life, were you concerned that you might reveal too much when you wrote about his final years?

Yes, of course. And also, Carrie and Olivia are going to read it. So I didn’t want to betray any confidence, but at the same time I think it was appropriate to describe the difficulty of that three-and-a-half-year period. It was difficult for me, and I was just his friend, I wasn’t part of his family. And it was a nightmare for them, what they had to live with on a daily basis. Alex and I would visit him every few months, and all that time we were keeping the secret, which was very fucking hard, because you’re basically lying to your friends all the time. With some of the people I lied to, they knew the truth but they never pushed back. They just accepted what I was doing was out of loyalty.

In the end I also felt that there was a way to write about his last years that doesn’t embarrass him, but instead shows the nobility he maintained throughout those horrible years of fighting with that disease. He remained himself. Even though it was sometimes difficult for him to get all the words out, he still maintained his sense of humour and a very sharp attitude about music and life. Right to the very end he was an exceptional thinker, a very moral, upstanding guy. In the last conversation we ever had together, I was still in awe of this man. So I thought the world should know that.

You mention the sense of humour that Neil had, and how it was a key part of his long relationship with you and Alex. When I interviewed Neil in 2012, I was surprised by how funny he could be – when he was talking about his love of birdwatching, or some of his early lyrics in songs like By-Tor And The Snow Dog.

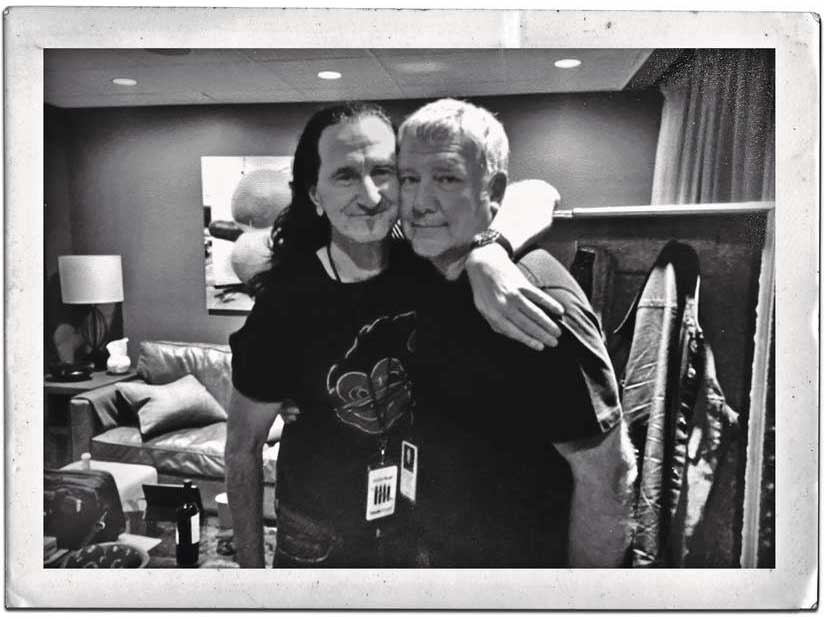

That was the thing that most people were surprised about when they met him, because they had this image of him as a serious guy, very intense, when in reality he was kind of a goof. We had so much fun together, and most of our fun was totally nonsensical. I know that it’s hard for fans to see him as this nonsensical dude, but he sure was. I think it helps that you have a character like Alex Lifeson with you at all times, because he’s the funniest human being on earth.

Neil adored Alex because of the way he was able to loosen him up, even in those last couple of years. The conversations during our visits were tough at times, because you didn’t want to keep talking about the disease and what he was going through. So I always reverted to making fun of Al, and it always made Neil laugh. Always, always, always. So even when Alex wasn’t being intentionally funny, he brought joy to Neil in those last years.

The late Taylor Hawkins was a huge fan of Neil’s, and when the Foo Fighters staged two tribute concerts for Taylor in 2022 at Wembley Stadium and the LA Forum, you and Alex were part of the all-star line-up, performing Rush songs with Dave Grohl, Chad Smith, Danny Carey and Omar Hakim taking turns on drums. In your book you say that this brought a sense of closure for you and Alex, where you could move on from grief to remembrance. Which is a beautiful way of putting it.

Those two shows were really unusual for very different reasons. The show in London was perhaps the most joyous celebration of loss that I could ever imagine. I’ve never seen so many musicians in one place, and the atmosphere backstage was profoundly positive. For five or six days before the show we were all holed up at a hotel with every other musician and all their friends and families. Every night you’d be in the bar with these folks, and there was no backbiting, no cynicism, no one-upmanship.

You could feel the spirit of Taylor and the love coming from the Foo Fighters family. That was really touching. And Dave Grohl is one of the most remarkable human beings I’ve ever had the pleasure to meet and work with. So here we were, Alex and I, having not played together in years, feeling pretty nervous about who’s going to play the drum parts. But it all came together, and in some ways it was maybe the greatest gig of my life. The whole atmosphere was like nothing I’d ever experienced.

But when we got to LA for the second show, things were a little different because of what that venue symbolises to me. Being back at the Forum, where my band had played for the last time, it felt like I was returning to the scene of the crime. So I tried to be as joyous as I was in London, but I couldn’t find that same head-space. I was much more withdrawn backstage at that show, thinking about things. But I walked away from it feeling that at least we had done justice to Taylor, and, in a small way, justice to Neil.

Have you ever considered doing something similar in memory of Neil? A celebration of Rush, with perhaps Dave Grohl and other drummers that Neil admired?

We did. We were planning to do a memorial in Toronto, but then the pandemic hit, and by the time we’d come out of it a couple of years had passed. We feel like we were robbed of the moment. But you never know. We still talk about it. If we can get our shit together we might be able to pull something off.

Are you working on new music?

Well, I have a few ideas. Recently I found a couple of tracks that were written for my solo album [My Favourite Headache, released in 2000]. My co-writer for that record, Ben Mink, discovered these demos, and when I listened to them I was not embarrassed at all, which was a good sign. I thought maybe if I could clean up these demos a little bit we could add them to the audio book of My Effin’ Life, and they would make for interesting listening as, you know, historic relics.

And while working on these tracks it was really interesting the way they made me feel. It made me want to write again. It made me want to get back on the horse, so to speak. So I think that bodes well for the future.

Why didn’t those two songs make the cut for My Favourite Headache?

Mainly because we had enough for the record. We were recording in Seattle with Matt Cameron [Soundgarden/Pearl Jam drummer], and we kept pulling out song after song for him to play. Finally I said to Ben: “Let’s have mercy on poor Matt!” So those two songs stayed in the can. But there were other reasons at the time.

Meaning what?

One of them was written right after Neil’s daughter Selena had passed away. The song is called Gone. It’s a song about loss. And even though it’s not exactly about Selena, it reverberates because it’s about all those losses, and what you feel when someone in your life is suddenly gone and you’re left with these feelings that you can’t make sense of. So at that time, out of respect to Neil, I thought I can’t put this on the record, it’s too raw.

And the other song?

It’s called I Am You Are, and again it’s a very personal song about what I was going through relationship-wise, and how tough it can be when you’re in the middle of an argument with your loved one or your band, whatever it is. It’s a beautiful song. Ithink both of these songs are good pieces of writing. So I’m happy that they will finally see the light of day.

You’ve stated unequivocally that with Neil’s passing there is no more Rush. But have you thought about making music again with Alex?

Alex and I have been in very different head-spaces for a few years, and our timing has not been good, mainly because I keep writing these effin’ books [he also wrote Geddy Lee’s Big Beautiful Book Of Bass], which takes me away from having time to spend doing my proper gig. But we talk about it. I see Alex all the time. We’re still as close as two pals can be. So it’s not beyond the realm of possibility that we would do some writing together.

Has Alex read My Effin’ Life?

Yes. He loved it. And he wrote me the most beautiful letter afterwards. He couldn’t have been more effusive. But, you know, he’s a Serbian guy, he’s very emotional. So… let’s just leave it at that.

It’s been emotional for you too, of course, to write this book and to talk about it now. So if we can end on a positive note, is there one memory you have from all the years in Rush that makes you think how fortunate you have been?

There are so many of those moments. When I want to laugh, I think about how we used to live, when we travelled together on the bus in the late seventies and early eighties. After a gig it was kind ofthe best time. You’d leave the gig and pile onto the bus, and you had all that post-gig energy still going on. You really needed to calm down.

So you’d have a few drinks, and maybe you’d take a Valium, and you’d watch some stupid movie together, and it was just jokes until you passed out or went to your little bunk bed on a shelf to sleep. These were moments when it was just the three of us and the few guys from our crew that we travelled with. You can’t replicate those moments. We could do another gig, Alex and I, with other people, but all those times we shared when it was the three of us, you can’t get that back.

My Effin’ Life is out now, published by Harper Collins.