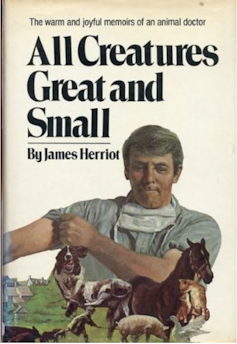

When Mum was pregnant with me, Dad bought her a paperback copy of James Herriot’s All Creatures Great and Small because it was an easy, pleasant read. I read my mother’s Pan paperback copy, with its cover image of sheep, farmers, and the vet’s vintage car, when I was growing up. We all watched the BBC adaptation when it was on television. And when my son is a bit older, I’m sure I’ll read the book to him or he’ll read it himself.

It is 50 years since All Creatures Great and Small was first published. In the time since, more than 60 million copies of the semi-autobiographical series of books about life as a vet in the 1930s and 40s Yorkshire Dales have been sold.

The books, eight in total were published in the UK, with some combined into omnibus versions making six American books.

There have been two film and three television series adaptations of them (the most recent British TV adaptation aired in Australia earlier this year). And the 1940s house in Thirsk, Yorkshire, where Herriot (real name James Alfred Wight) lived and worked is now a museum, attracting visitors from all over the world.

What is the key to the books’ success? I think it is the combination of humanity and humour in Herriot’s writing.

Very human characters

James Herriott was the pen name of Wight, a Yorkshire vet. He used a pseudonym because the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons did not allow vets to advertise. He also wanted to protect the privacy of the people on whom his characters were based.

Born in England in 1916, Wight grew up and graduated from veterinary school in Scotland before returning to England to practice. He first worked in urban Sunderland, but moved to Thirsk after just six months as he wanted to be a country vet. He was in the Royal Air Force in 1942-3, but was discharged after being deemed unfit to fly for health reasons. Following the end of the war, Wight worked as a vet in and around Thirsk until his retirement in 1989. He lived in Yorkshire until his death in 1996.

Wight kept diaries as a child and made copious professional notes, but began to write seriously in his 50s after his wife Joan encouraged him to do so. He analysed books by authors whose work he enjoyed, including the humourist P.G. Wodehouse. His first published book, If Only They Could Talk, was published in Britain in 1970. It had modest sales, as did the sequel It Shouldn’t Happen to a Vet, published in 1972.

When the two books were combined into All Creatures Great and Small for US publication, also in 1972, the omnibus volume had huge success. From there, a franchise was born.

The books are episodic, with vignettes bound together by the narrative of Jim’s life (the character Jim is clearly based on Wight himself). He slowly moves from being a newcomer to the fictional town of Darrowby to acceptance within the originally sceptical community, marrying and building his own family and professional life.

Animals are part of every story, but the human characters really shine. These include the brothers Siegfried and Tristan Farnon, with whom Jim shares the vet practice, the wealthy widow Mrs Pumphrey, and a series of dour Yorkshire farmers including Jim’s future father-in-law Mr Alderson.

Some like Siegfried, Tristan and Mrs Pumphrey were based on real people, others were combinations of real people; still others purely made up. This enabled Herriot to create characters that feel authentic.

Mrs Pumphrey, who pampers and fusses over her beloved Pekingese dog Tricki Woo, was one of the few characters recognisable to the real person on whom she was based: Miss Marjorie Warner (and her Pekingese Bambi).

Read more: Pets and owners - you can learn a lot about one by studying the other

The character is a figure of fun. She uses euphemistic phrases like “flop bott” to describe her dog’s various ailments and makes numerous calls to the vets for both real and imagined illnesses on behalf of Tricki Woo, and later, her pet pig Nugent. Still, she is painted as generous, kind and caring.

Life is hard at times. In one story, the famously aggressive cattle on Mr Copfield’s farm crush Jim against the wall, charging, kicking and whipping him in the face with faeces and urine-sodden tails.

The farmer’s sons help him wrestle them into submission, all in “the spirit of a game with encouragement to the man in action”.

Jim’s work is physically demanding. Being woken by a phone call in the middle of the night to drive to a cold farm and tend to a sick animal is commonplace. Still his willingness to do it earns him respect and hospitality on the bleak farms, where farmers might invite Jim in “for a bit o’ dinner” or “slip half a dozen eggs into the car”. There are moments of joyful professional satisfaction, too, such as when Jim safely delivers a newborn lamb and its twin, which has been caught in the ewe’s birth canal.

Herriot laughs at himself as often as he does at the people around him.

Read more: Why your veterinarian may refuse to euthanise your pet

Nostalgia

Herriot’s books are set in the 30s, 40s and 50s, some years earlier than his real-life experiences. Nostalgia for what has been called a “fast-disappearing way of life” has unquestionably been part of the appeal of the franchise. They became best-sellers in the USA before they did in the UK.

The absence of story lines that might lead to “difficult” conversations around political or sensitive topics also make them comfortable, escapist entertainment. Even in Vet in Harness, set when Siegfried and Jim are in the Royal Air Force, the stories focus on the personal and human, balancing humour and hardship.

Wight’s children still receive letters from readers around the world telling how his books helped them cope with difficult times. One American man said the books were so uplifting they helped save his life during a bout of severe depression. According to his daugher, Rosie, Wight himself suffered from “melancholic episodes”.

With pet ownership on the rise animal stories will remain part of our culture. But it’s the vision of easy humanity in Herriot’s stories that has kept us coming back for more.

Helen Young does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.