In 2014, PC Gamer awarded horror adventure Alien: Isolation Game of the Year, praising its reactive AI and exhaustively faithful environmental design. At the time, staff writer Andy Kelly called it "probably the bravest, most subversive 'AAA' game of the year."

"I've played through the game twice now, and the alien still surprises and scares me," he wrote then.

Coming up on a decade later, Andy's definitely played through Alien: Isolation more than twice—and probably thought and written more about it than anyone on the planet outside game developer The Creative Assembly. Today he's publishing a book about a game that has firmly etched itself into the PC gaming canon, and we invited him back to PC Gamer to share a snippet of it.

Here's Andy:

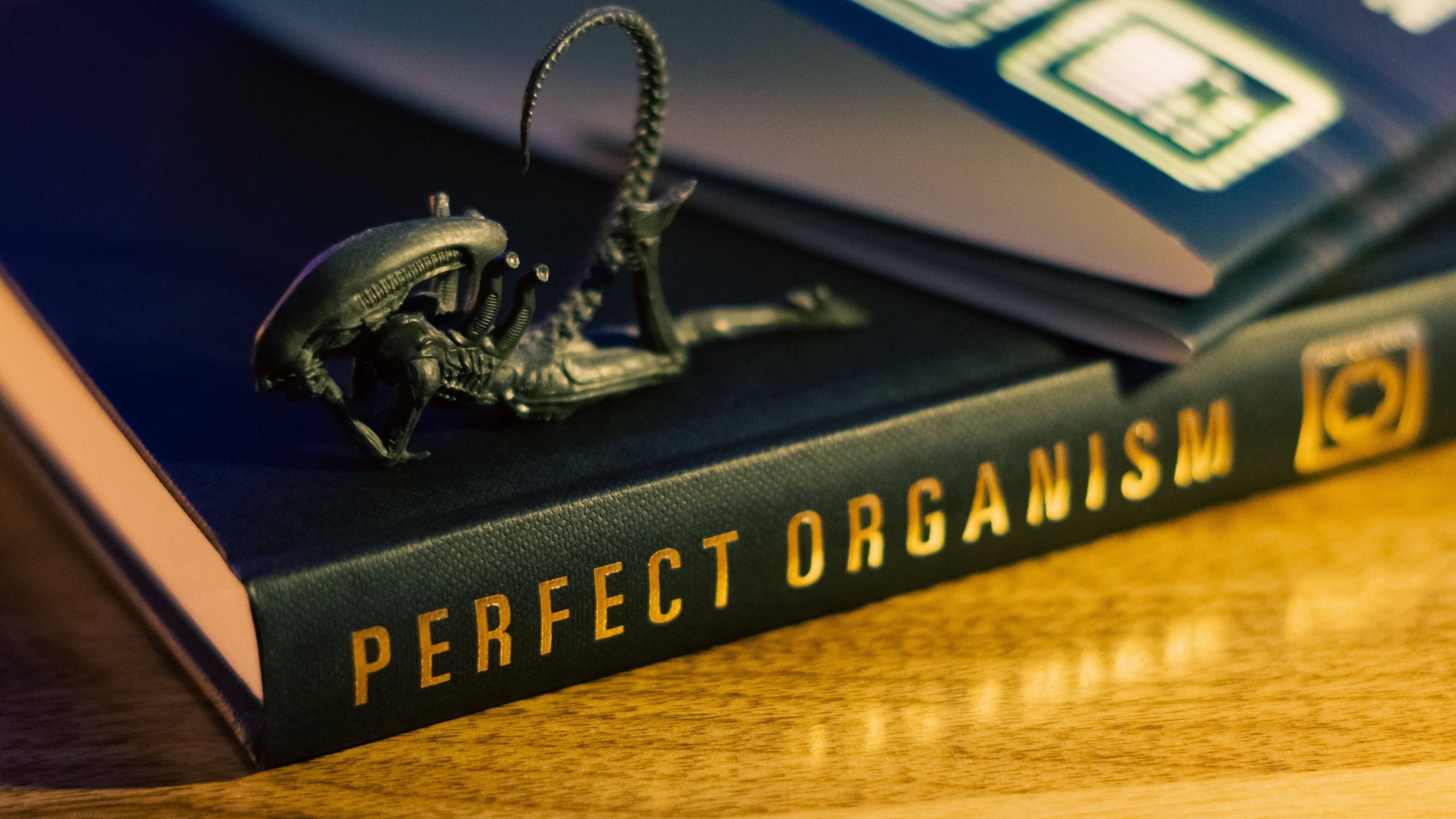

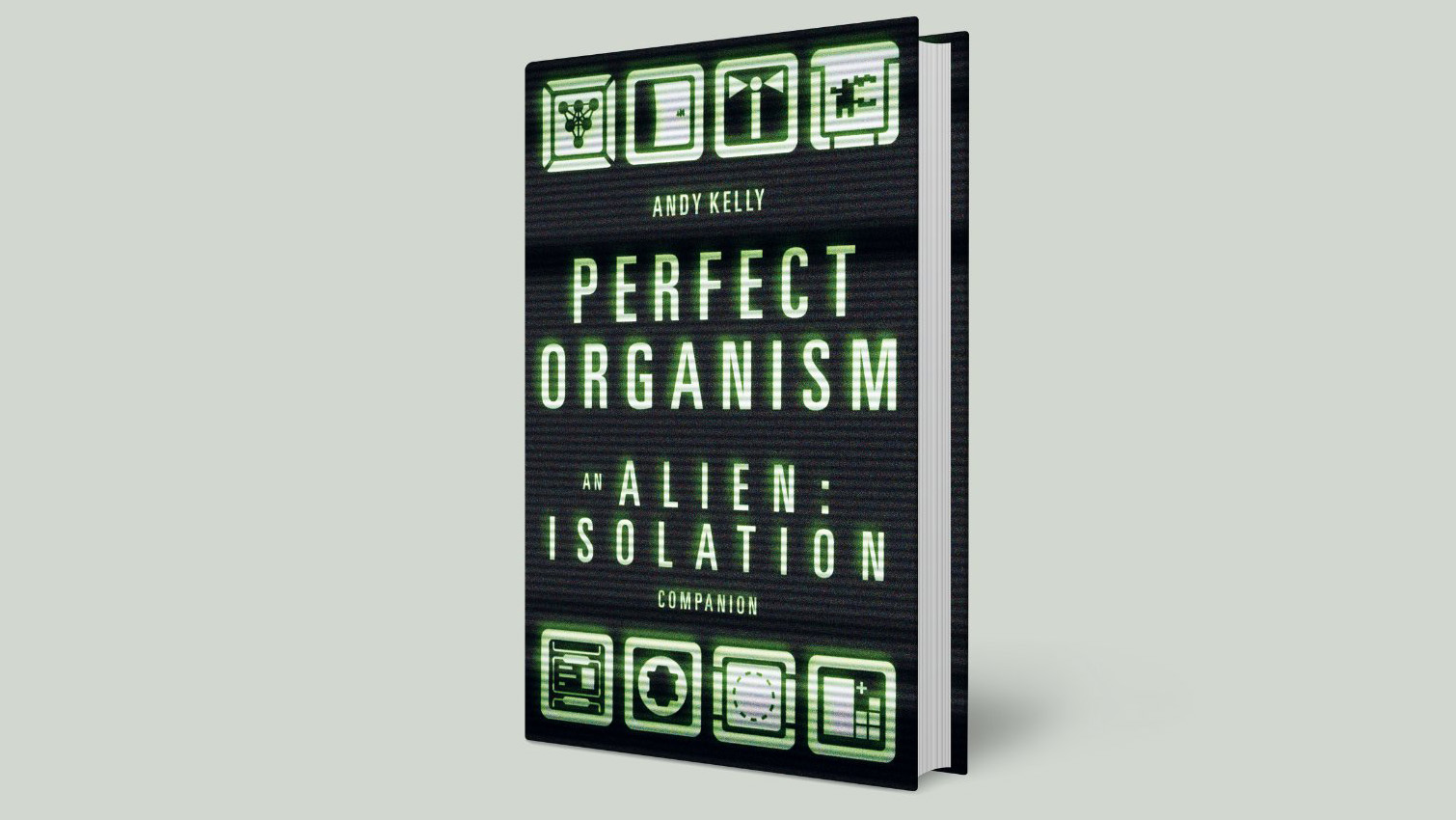

The only thing I've obsessed over more in my life than Ridley Scott's 1979 horror masterpiece Alien is Creative Assembly's 2014 horror masterpiece Alien: Isolation. So much so that I've written an entire book about it—an unofficial companion to the greatest horror video game ever made—an excerpt of which you can read below.

This chapter is taken from Perfect Organism's Mission Guide, which makes up the bulk of the book. It's a huge level-by-level deep dive into the game that analyses the art, AI, audio, movie connections, level design, easter eggs, development secrets, and other illuminating nuggets of trivia and insight. The book also tells the story of the game's creation, reveals content that was cut, looks back at its legacy 10 years after it launched, and more. — Andy Kelly

Disclosure: Andy Kelly was a writer for PC Gamer for eight years. He departed in 2021, and now works for game publisher Devolver Digital. We knew he wouldn't be able to resist getting Alien on the website one more time.

Mission 1: Closing the Book

UK: Perfect Organism is on sale now

US: Perfect Organism is available for pre-order and ships in November

A figure in a welding mask hunches over some unidentifiable piece of futuristic machinery. Sparks fly from a plasma torch, but their work is interrupted by a voice: 'Ripley?' They raise their mask, revealing a woman's face with dark, intense eyes and a forehead moist with sweat. This is our introduction to Amanda Ripley, daughter of Ellen Ripley, an engineer working in a remote corner of space. The man—or, more accurately, artificial person—is Samuels, a representative of the powerful, space-conquering Weyland-Yutani corporation. 'I'm Samuels,' he says. 'I work for the Company.'

This is a loaded word in the Alien series. Weyland-Yutani's reach extends so far, and the organisation is so entrenched in the everyday industry, politics and economics of space, that the need to refer to it by name has long since passed. Ripley pointedly pulls her mask back down and reignites her torch. This makes her attitude towards the corporation clear. Her mother was on their payroll when she went missing, and she understandably holds a grudge.

In the comic Aliens: Resistance, written by Brian Wood and published by Dark Horse Comics, we learn that Ripley's attempts to get a straight answer from Weyland-Yutani about what happened to the Nostromo and her missing crew have been frustratingly fruitless. 'They string me along, give me just enough bureaucratic red tape to wade through to keep me hoping,' she tells a Company-appointed therapist she suspects has been hired to encourage her to move on and stop asking questions. 'They want me on a leash.'

Then Samuels mentions something that makes her drop her guard. A commercial salvage ship, the Anesidora, has located the Nostromo's flight recorder: a potential clue to the whereabouts of her mother. It's being held on Sevastopol, a backwater space station, and Samuels wants her to go there with him. As he details the mission, Ripley makes him a cup of coffee—a nice callback to Aliens, where her mother did the same for Carter Burke and Lt Gorman as they tried to convince her to travel back to LV-426 with them.

'I've been cleared to offer you a place on the Torrens if you want to come along,' says Samuels, referring to a ship that we'll be visiting soon. 'Maybe there'll be some closure for you.' The camera lingers on Ripley's face as she processes everything she's just learned. It's clear she doesn't want to play ball with the Company, and doesn't trust Samuels, but can she really give up an opportunity to find out what happened to her mother?

As Ripley moves through a corridor, fluorescent lights flicker on and make it feel like the ship is waking up alongside her

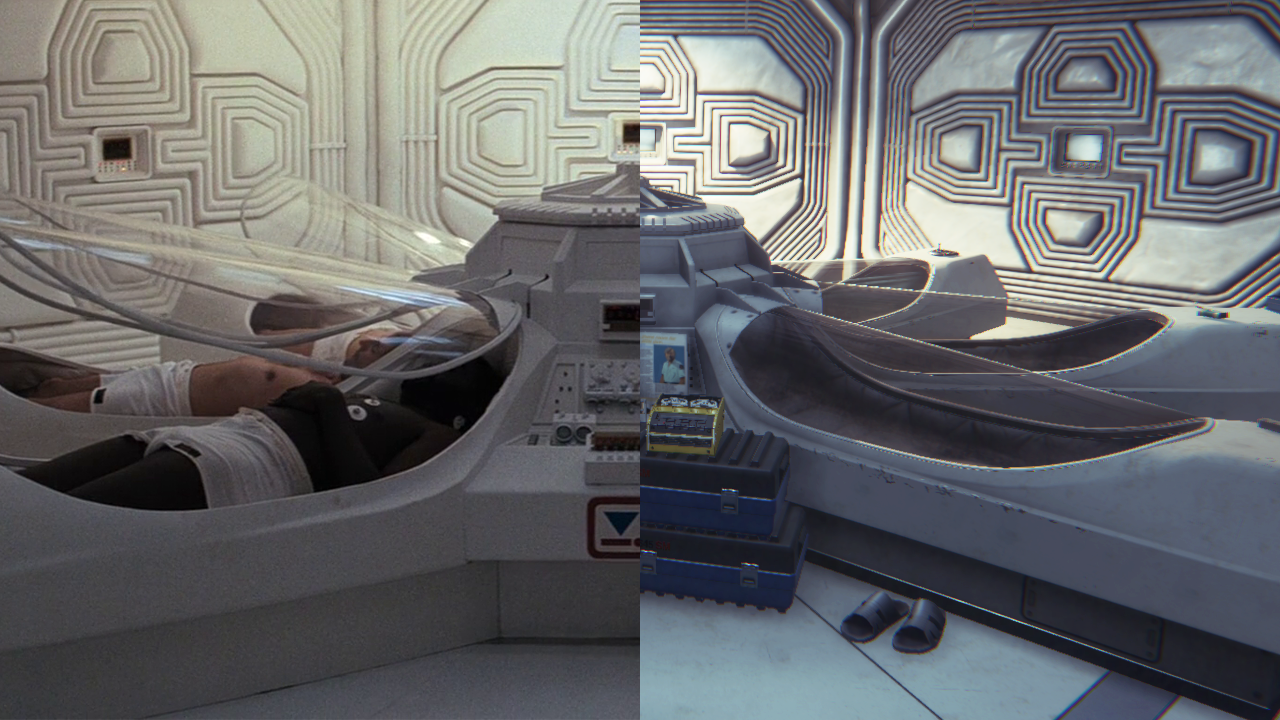

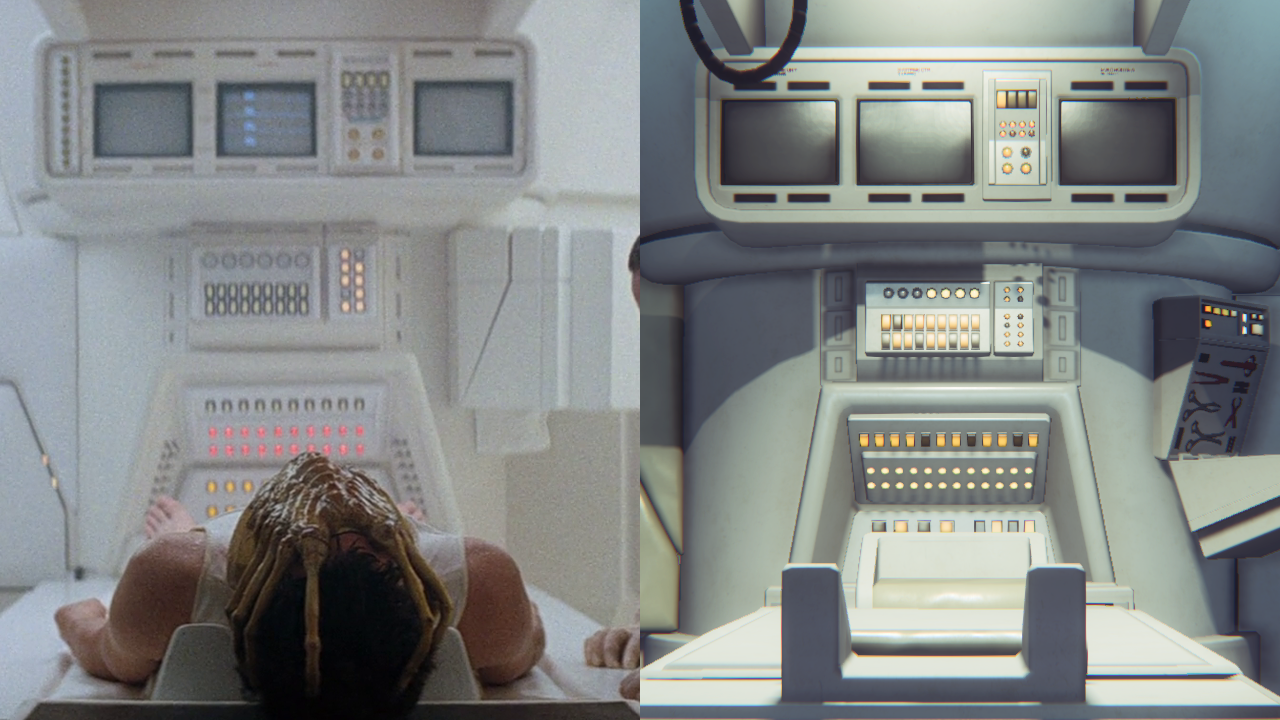

The next thing we see is Ripley emerging from a transparent, sarcophagus-like hypersleep pod aboard the Torrens. This octagonal, padded room is quiet except for the distant rumble of the engines and the chirps of nearby computers. This location will be instantly recognisable to anyone who's seen Alien, as it's a near-perfect replica of the hypersleep chamber from the 1979 movie. This iconic set was designed by Benjamín Fernández, a Spanish art director, who used hidden hydraulic rams to make the flower-like pods open slowly.

Ripley inserts an ID card into a terminal, presumably to alert the crew of the Torrens that she's awake. Explore the room and you'll find a few interesting objects, including a book with a medieval coat of arms on the cover titled War in Totality—a reference to developer Creative Assembly's popular Total War series of military strategy games. There are several photos stuck to the walls too, including a picture of the White Cliffs of Dover. Details like these make the Torrens, and later Sevastopol, feel real and lived-in.

The hypersleep chamber also marks the first of many appearances of Alien's famous drinking bird. This novelty toy, whose head bobs up and down as it appears to sip from a glass of water, was one of many strange knick-knacks decorating the Nostromo—which Alien writer Dan O'Bannon explained as being 'from various gift shops around the universe, wherever they stopped off. I figured that wherever you go there will always be gift shops.' Sevastopol and the Torrens are similarly littered with toys and other assorted junk collected from around the galaxy. Life in deep space is hard, so it's no surprise that people want to liven up the places where they live and work.

Ripley leaves the hypersleep chamber and it's immediately obvious from the layout of the ship that the Torrens has a lot in common with the Nostromo. Both vessels are Lockmart CM-88B Bison towing ships, but the Torrens has been refitted as a transport vessel, used for moving people around rather than large cargo like the refinery in Alien. This is reflected in its appearance, which is more comfortable and less industrial than its 1979 counterpart. It's not quite the Enterprise-D, but for a spacecraft in the Alien universe it's positively luxurious. Warm colours and soft lighting set this vessel apart from its submarine-like cinematic counterpart. As Ripley moves through a corridor, fluorescent lights flicker on and make it feel like the ship is waking up alongside her.

Move the camera down towards Ripley's feet and you'll notice that she's in her underwear. Ridley Scott originally wanted the crew to be completely naked in their hypersleep pods, but the studio was dead set against it. Scott actually shot the scene twice—once with the cast wearing underwear and once without—just in case they had a change of heart. 'I wanted to have a total sense of reality and rawness to this whole film,' he said in a director's commentary recorded for Alien's original DVD release. 'Because the realer and truer you get, the scarier it gets later. But I lost that argument for obvious reasons.'

In a nod, perhaps, to influential first-person shooter Half-Life, Ripley locates a locker with her name on it and retrieves her clothes. You can take a shower, too, whether you already have your clothes on or not. A crew roster on a screen reveals who she's travelling to Sevastopol with, including Christopher Samuels (the synthetic human we already met in the intro), another Company employee named Nina Taylor and the Torrens' skeleton crew: Diane Verlaine, the ship's owner and captain, and William Connor, her second officer.

Nearby, a random assortment of papers is stuck to a wall—including one bearing the name Weylan-Yutani, without the D. This is what the Company was named in the original movie, before it was retconned to Weyland-Yutani in Aliens. According to production designer Ron Cobb, who came up with the name, he originally wanted to call the company Leyland-Toyota, suggesting an alliance between the British and the Japanese in this vision of the future. But this wasn't allowed for copyright reasons, 'so changing the letters gave me 'Weylan', and 'Yutani' was a Japanese neighbour of mine.'

This otherwise unremarkable scrap of bureaucratic paperwork also has the lesser used 1979 version of the corporation's logo printed on it, which Cobb based on the winged sun: a solar symbol associated with divinity, royalty and power that was used by the Egyptians, Persians and Mesopotamians in ancient times. Alien: Isolation is impressively zealous when it comes to honouring the original movie and using it as the primary source material, but all other references to Weyland-Yutani in the game, including later appearances of the logo, are based on the series' current official post-Aliens canon. This random piece of environmental decoration, possibly left over from an earlier iteration of the game, makes me wonder if this wasn't always the case.

Exiting the locker room, you can now decide who to speak to first: Samuels in the medbay or Taylor in the communal kitchen/lounge area. The dialogue changes slightly depending on who you bump into first, but not in any significant way. You can also head straight for the bridge if you're feeling anti-social, but you'll miss out on some interesting world-building.

In the medbay, Ripley asks if Samuels woke up early. 'Well, I don't really need as much sleep as the rest of you,' he says, pointedly reminding us that he's not made from the same flesh and blood as the rest of the crew. He notes, as if we hadn't guessed already, that the Torrens is a 'very similar model' to the Nostromo. Ripley says she's worked engineering jobs on ships like this before. We get the sense that space travel is nothing special for her, which is a nice echo of the original film, where it was treated with a similar lack of reverence. This is not the final frontier: just a place where people go to do a job.

The medbay is a brilliant recreation of the infirmary set from the movie. It even has a functional CT scanner—based on a design by Ron Cobb—which folds away into a concealed, glass-covered chamber when a button is pushed. The room's ambient background noise, including a rhythmic, pulsing sound that sweeps in hypnotic waves, is also lifted directly from the film. Fans of Ridley Scott's other masterpiece, Blade Runner, may recognise this sound. It was reused as part of the futuristic ambience of Deckard's apartment.

In the lounge, Taylor is struggling with the hangover-like after effects of hypersleep. 'I don't do long-haul very often,' she says. 'Most legal execs don't travel further than the coffee machine.' Ripley reassures her that you get used to it, another clue that our hero is accustomed to travelling in deep space.

While Ridley Scott was overseeing the construction of the Nostromo bridge set, he asked the carpenters to lower the ceiling to add to the crew's feeling of isolation and claustrophobia

Taylor is, as her previous dialogue suggested, part of Weyland-Yutani's legal team. She's been tasked with overseeing the handover of the Nostromo flight recorder and compiling a final accident report detailing exactly what happened to the missing ship. In a revealing line of dialogue she notes that this will look great to her superiors—before realising how insensitive that sounds. Ripley is unfazed. 'It's okay. We'll both get what we want, right?'

The lounge will be instantly familiar to anyone who's seen Alien, being a near-identical replica of the room where Kane famously 'gave birth' to the xenomorph that terrorised the crew of the Nostromo. In the kitchen there are replicas of the futuristic-looking coffee dispensers that appeared in the movie. Alien's set designers used a pair of real-world Braun Aromaster KF20 coffee machines as the basis for these, as well as a Krups 223 coffee grinder—which also appeared, more famously, in Back to the Future Part II as Mr Fusion, the 'home energy reactor' retro-fitted to Doc Brown's time machine.

Overflowing ashtrays, discarded beer cans and other junk give the Torrens a similarly untidy, lived-in feel as the Nostromo's shared spaces; although Verlaine's ship isn't quite as grimy. On a nearby terminal, Ripley reads a message sent to Taylor outlining the Nostromo incident and listing the missing crew. The author, a Weyland-Yutani employee named Saul, writes about this tragedy in the cold, matter-of-fact way only a true Company man could.

Ripley moves to the bridge and meets Verlaine face-to-face for the first time. The captain is wearing a clean, neat uniform, reflecting the pride she takes in her ship. Under the jacket we catch a glimpse of a pink paisley shirt, which recalls Brett's Hawaiian shirt. Sartorial details like this reinforce the idea that Alien: Isolation is presenting us with a seventies vision of the future.

While Ridley Scott was overseeing the construction of the Nostromo bridge set, he asked the carpenters to lower the ceiling to add to the crew's feeling of isolation and claustrophobia. Even though the Torrens' bridge is much brighter, this dropped ceiling still gives the place an oppressive feel. It's a subtly brilliant piece of off-the-cuff set design from Scott, and one that informs many of the new areas Creative Assembly went on to design for Sevastopol.

You can also catch a tantalising glimpse of the Torrens' humming, womb-like MU-TH-UR supercomputer chamber here through a window—but, alas, it's sealed off. You can only access this iconic location for yourself, albeit on another starship, in the game's Nostromo DLC missions. Then, when you're done exploring, it's just a matter of picking up a briefing file and triggering a dramatic cutscene that sets Alien: Isolation's story fully in motion.

Bringing an image of Sevastopol up on a flickering CRT screen reveals that the station is seriously damaged—including, in a stroke of bad luck for Ripley and co., the dry-dock bay. This means Verlaine is unable to dock the Torrens and attempts to contact the station for help, only to receive a garbled radio message from someone named Waits, a Colonial Marshal. Through the static we can make out the words 'serious situation', but not much else.

Ripley, Samuels and Taylor are left with no choice but to strap on the Torrens' yellow pressure suits and spacewalk over to Sevastopol via a precariously long cable. Then, suddenly, disaster strikes. An explosion sends a hulking chunk of metal debris hurtling towards the cable, snapping it and sending the three characters spinning off in different directions. Ripley manages to grab hold of the station before she's swept away into the darkness of space, narrowly escaping into an airlock, unaware of the nightmare that awaits her.