Speaking to Classic Rock in 2015 for his fifth and final solo album, Higher Truth, the late Chris Cornell spoke with the equanimity of one who had seen it all and done most of it. As frontman with Soundgarden he was a pivotal cog in the musical revolution that cleared shop at the start of the 1990s, and later joined forces with the musical nucleus of Rage Against The Machine to form Audioslave. He died in 2017.

Ask Chris Cornell a question, any question, and off he will go: on tangents, down alleyways, occasional cul-de-sacs, but usually on to wide avenues ablaze with the memories of a life lived fully.

Speaking from Miami, Florida, at 10.30 in the morning local time, Cornell’s American PR calls with advance warning that his charge’s schedule is running late. It’s not difficult to imagine why, or to imagine his world: a land strewn with donkeys struggling to make do with no hind legs.

With a four-octave vocal range and homes in as many cities, this once grandly reluctant rock star seems today to be as much a part of the classic rock firmament as anyone you might care to nominate. What’s more, at last he seems to be at peace with this.

On Higher Truth you revisit the acoustic format of your 2011 album, Songbook. What was the thinking behind that?

Really it was the culmination of touring, of about four years or so of playing acoustic shows. I played the UK, Europe, the USA, Australia – I played everywhere. And the shows had a different feeling to them, kind of like a church-y environment. And I liked that; I liked the freedom that this gave me. Being in a band means certain limitations. Obviously I love Soundgarden and I’m very proud of the music we’ve made. But people know that Soundgarden isn’t going to play, say, a reggae song or something. The music isn’t stripped down. But in this format it is stripped down.

You were extremely lucky when Soundgarden became an A-list rock band. Or were you? The class of Seattle in the 1990s were the first generation of bands to challenge the notion that bigger is better.

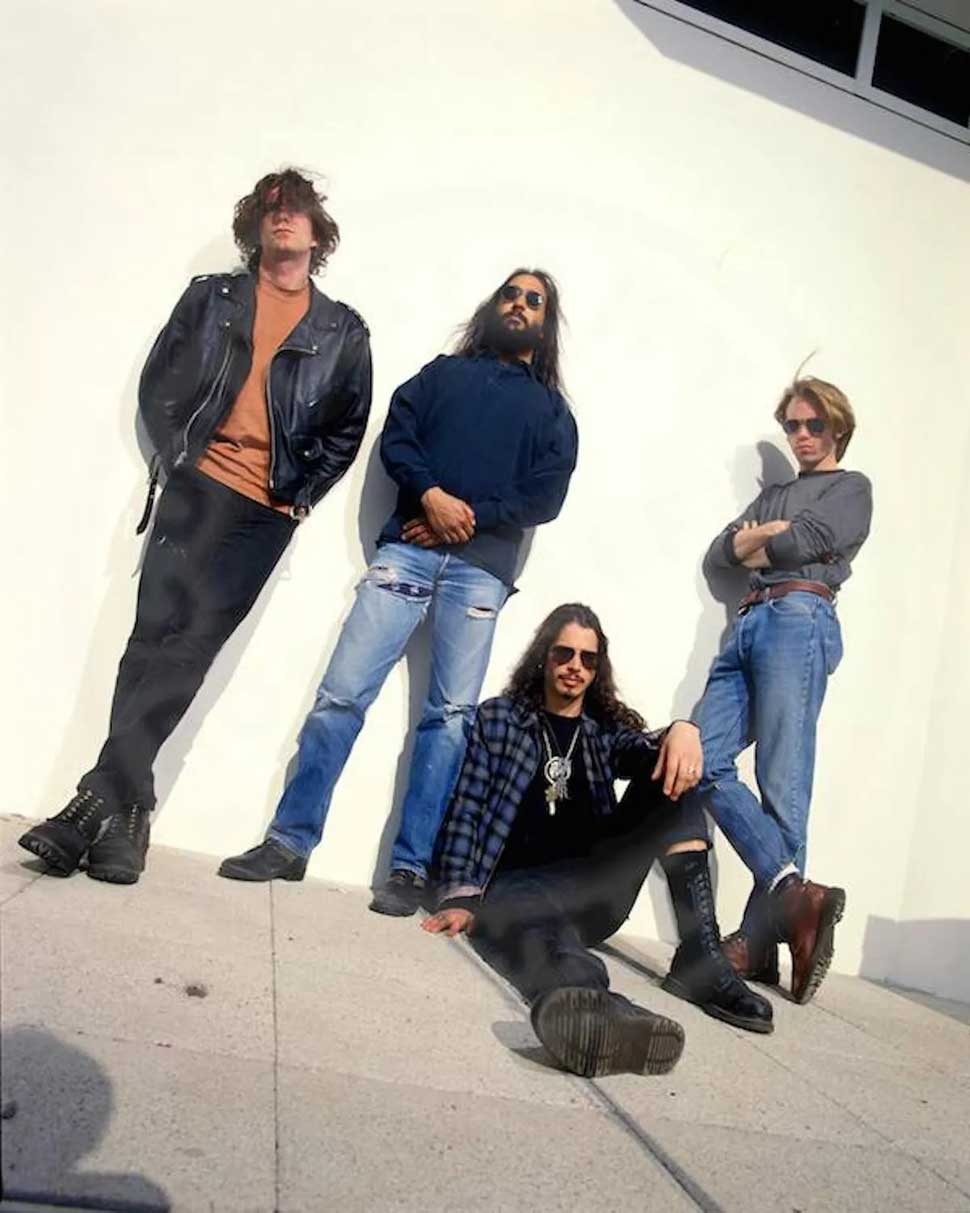

That’s right. And for a while there I was very stressed out. Before that, every single person in our audience had been recruited through our hard work. It was us touring in a van, thousands of miles, just the four of us and one crew guy. It didn’t look like the route to mainstream success. But we just toured constantly, and got played on college radio every now and again. But although we came to be seen as being peers of Nirvana and Pearl Jam, we actually preceded them.

We were the ones on the road who saw the door opening a crack, with bands like Red Hot Chili Peppers, Metallica and Jane’s Addiction who were testing the mettle of record company marketing departments. These are the people that told us we were going to be the future of rock, stuff like that. Well, we came from the world of fanzines, and we were fans of Bad Brains and Meat Puppets, and suddenly we were being mentioned in the same sentence as bands like Poison or Great White. It was a bit confusing.

When Soundgarden came to an end did you feel at all lost?

No, not really. I felt that things had definitely changed for me, but that was a challenge I welcomed. And musically I really felt that Soundgarden had gone out on top. I was proud of everything we’d achieved, musically, and I was very pleased we hadn’t stuck around for too long and done anything to cheapen the name. Of course, we would get back together – completely by accident, I might add – and make [2012’s] King Animal, so whatever feelings I may have had about there being any unfinished business were dealt with by that.

Your first solo album was Euphoria Morning, released in 1999. Did you feel exposed without a band around you?

It was a little scary, yes. Everything I’d done to that point had been collaborative, whether with Soundgarden or Temple Of The Dog. But I knew I wasn’t crazy to think I could do something that didn’t have a concept I could charge into. But I was happy with the reception it got – I wasn’t shot in the knees or anything.

For your third solo album, Scream, you worked with R&B producer Timbaland and Justin Timberlake. It was less favourably received. What are your thoughts on that record now?

Well, despite the fact that the people I worked with on that album were known for making music I had very little knowledge of, I’m really happy with what came out of those collaborations. It really was more than a Chris Cornell solo record. It also broke away from what I think was my own rigid manifesto as to how I should sound, a rigid manifesto that has nothing to do with what is good about songwriting. I was an ‘alternative’ artist, but when I started out there was no such label as ‘alternative music’. So it was good for me to break out of that box.

When you co-founded Audioslave in 2001 you must have been aware that you were conforming to one of the great clichés of rock’n’roll: the supergroup.

Of course! And the thing about supergroups is this: most of them were complete shit. Aside from Blind Faith – who were only together for about a year anyway – The Yardbirds and The Faces, the bar really wasn’t very high. But I was certain that I wanted to start writing music again in an organic fashion. And it didn’t get much more organic than writing in a tiny, dark room in North Hollywood. I was sure that people would want to hear what we were doing, but of course at the time there were lots of negative grumbles. And hearing all of this negativity kind of made me a booster for the band, even though at the time my life was chaos.

How was it chaos?

I was in the middle of my marriage [to Susan Silver, one-time manager of Soundgarden] falling apart, which had been falling apart for a long time. Along with this I was slipping into alcoholism, so I was dealing with the marriage issue in that way. I’d drunk from the age of seventeen right up to my mid-thirties, and during that time the drinking had gone from recreational to being a pattern of abuse.

So this was the guy that Audioslave had to deal with. Don’t get me wrong, we made three terrific albums together despite everything that was happening in my life, and I’m very proud of that. But I think were it not for the state I was in that things could’ve been different, and that’s a bit of a shame. But at that time, for the most part, I was a drunk. Well, I was sober at the end, but it takes time to try and get out of the mindset that got you to this point in the first place.

Were drugs a big part of your life during this period?

They were toward the end [of his alcoholism]. But drugs for me were never the key thing, they were never the first thing. If I woke up in the morning with a terrible hangover – maybe with a show to do – then drugs were a way of getting me through that hangover. But for me it was primarily about the drink. Although having said that, there is a high level of self-deception that goes along with people who take a lot of drugs or who drink to excess.

You’d seen the logical conclusion of intemperance with both Kurt Cobain and Mother Love Bone’s Andrew Wood. Didn’t that concern you?

That’s what I mean by self-deception. I didn’t consider myself to be part of that group. But at the same time I didn’t give a shit. Alcohol is a depressant, so I got depressed. I understood that. But meth and heroin, I knew what that was too, and I also knew the result of those drugs was that people would die. Drinking, I thought, was different.

The master tapes of the Temple Of The Dog album, which was a tribute to Andrew Wood, are being ‘held hostage’ by Rajan Parashar, who owned the studio where it was recorded. A&M, the label that released the album, have filed a lawsuit to retrieve the tapes. What do you think about that?

I feel it’s something that doesn’t really concern me. I don’t feel like a participant in this at all. The whole situation just doesn’t seem to move. It’s just silly. The fight isn’t between me and the guy who has the tapes, but between the guy who has the tapes and the record company. But although I don’t feel that this particular argument has anything to do with me, I do feel the issue of ownership is relevant. There is the fact that although an artist writes and records a song or an album, the copyright, the ownership of that music belongs to the record company. And that’s something I’d like to see more widely discussed.

Inevitably you’re associated with Seattle, but where do you actually live these days?

At the moment I’m in Miami, where we have a place. I do like it here, but it can get really humid. We also have places in New York, Paris and Rome. I like Rome a lot. I think it’s just such an exciting city, especially for an American, with all the history. I find it odd that people tend to concentrate on how crazy people are in urban environments. I’m surprised there’s not more crazy people. If you think about it, in huge cities such as LA or New York or London, very little actually goes wrong. Considering how many people there are there, they’re actually pretty safe places to live.

Speaking of crazy people, the race to become the Republican presidential candidate is in full swing, with Donald Trump leading the way. What do you think of him?

I wasn’t impressed by Donald Trump. Actually, me and my brother‑in-law were talking about this the other day, about how in the US, political debate seems to have become nothing more than right-wing entertainment. It’s crazier than it’s ever been. For me, I want a president who is a moderate guy that is credible, someone who understands his democratic role but also is willing to offer tax breaks. But this right-wing extremism doesn’t make for a better presidency, or economy, or anything.

Before it was announced that Sam Smith is doing the theme song for the new James Bond film, there were rumours that Radiohead were going to do one. Since you’ve recorded one, do you think they should have done it?

I don’t think they should do a Bond theme. They have nothing at all to gain and everything to lose by doing so. They’ve spent years creating and carving out their own corner, so why would they poke their heads out of that world? I do think that were they to do a Bond theme it would be great, but I just can’t see the point in them doing so. Even when I did it [with You Know My Name, for the 2006 film Casino Royale] it was a stretch, something really different. And then they had Jack White do one, and that was even more of a departure. But for me, a Bond theme should be a classic pop song and should be something timeless.

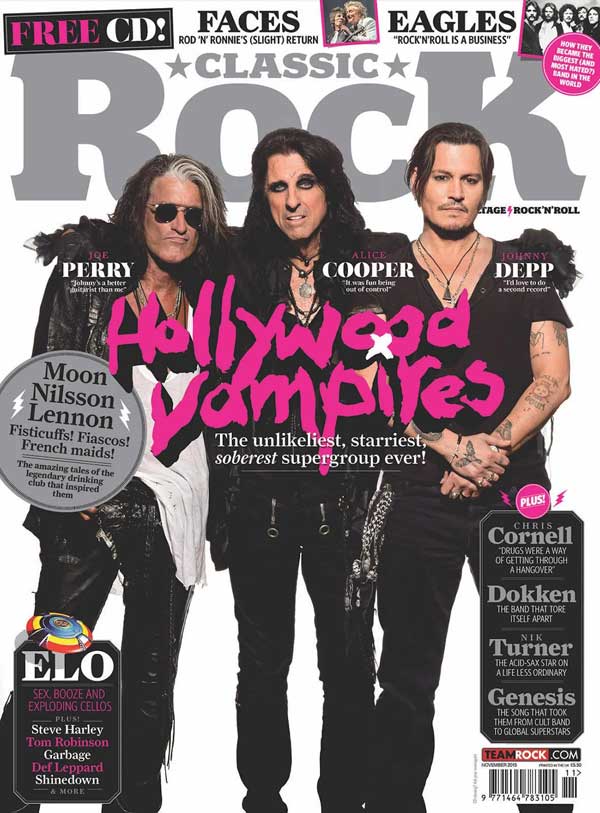

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 216, published in October 2015.