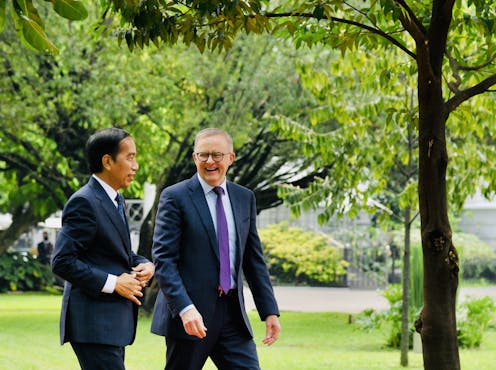

Early June marked a new highlight for the Indonesia-Australia relationship, as newly elected Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese chose Jakarta as the very first destination for his official overseas trip.

Albanese brought several issues to discuss with President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo: global and regional economic issues, post-pandemic economic recovery, and the implementation of the Indonesia-Australia Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (IA-CEPA).

Indeed, it has become a tradition for new Australian prime ministers to fly to Jakarta as their first bilateral visit. Albanese’s predecessor Scott Morrison did the same in 2018 after he was sworn in.

The first destination – be it a country or a region in a country – visited by a state leader signals that it must be among their highest-priority places to embrace.

For Australia, Indonesia must be a very important counterpart for Albanese to implement his foreign affairs policies and to secure the country’s interest in the South Pacific.

In contrast, Australia is not Indonesia’s top priority, but nevertheless Jokowi should not take Albanese’s approach for granted.

Australia to Indonesia: from geopolitics to economic interests

There are at least two reasons why Indonesia has become Albanese’s top priority for bilateral relations.

First, Australia needs a strong relationship with Indonesia to strengthen its influence in Southeast Asia and balance China’s regional dominance.

China’s influence in Southeast Asia and the South Pacific is growing, prompting Australia to seek ways to make its country more geopolitically secure.

Cooperation among South Pacific countries in the Pacific Islands Forum, such as Fiji, Solomon Islands, Kiribati, Samoa, Niue and Papua New Guinea, has begun to involve security issues. Many have allowed China to place its armed forces in Pacific waters to secure China’s economic interests.

Australia, of course, does not want the area directly adjacent to its waters to be controlled by China.

Until now, ASEAN member countries can balance themselves from the influence of China and the United States. And Indonesia will become the chairman of ASEAN in 2023, placing Southeast Asia’s largest economy in a strategic position.

With its presence in Southeast Asia, Australia can withstand the influence of China’s soft power in the region. If Southeast Asian countries can reduce their economic dependence on China, that will positively affect Australia’s security.

Second, Australia needs Indonesia to face a trade war with China.

Beijing has created a trade war against Canberra by increasing tariffs on wine, lobster, barley, coal, beef, cotton and timber imported from Australia. This followed Australia’s decision to block China’s tech giant Huawei from developing 5G infrastructure in the country, and its accusation that China was responsible for the widespread coronavirus.

Until 2020, China was Australia’s largest trading partner for both exports and imports, but the trade war has pushed Australia to divert its trade focus from China to other countries in the region, including Indonesia.

Australia may set its sights on increasing sales of wine in Singapore, livestock in Indonesia and the Philippines, and barley in Vietnam and Thailand.

Indonesia to Australia: how to respond?

Australia is not Indonesia’s top priority, because Indonesia sees itself as capable of becoming a strong player in the region even without Australian help.

What’s more, Australia’s decision to ally itself most closely with the United Kingdom and the United States – through the AUKUS Agreement – is not necessarily in Indonesia’s interest.

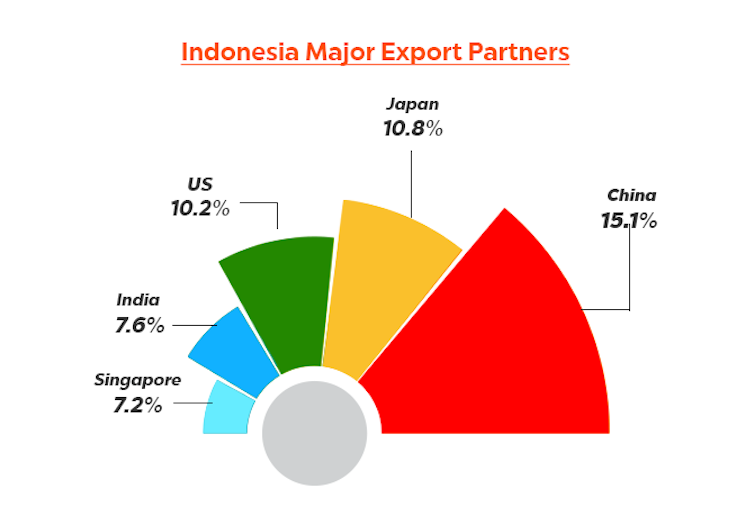

During the first quarter of this year, Australia was not among Indonesia’s top five export destinations for non-oil and gas commodities, and vice versa.

However, Indonesia can take advantage of this momentum, which is the way how Albanese is going to prioritise Indonesia as one of Australia’s main partners in his administration.

In a moment like this, Jakarta can try to persuade Canberra to refrain from interfering in Papua’s politics.

As one of Indonesia’s neighbours, Australia has a great interest in a peaceful resolution of the Papua conflict, and this often affects Australia’s relations with Indonesia.

Interfering in Papua’s politics can affect relations between countries in the region, as happened between Indonesia and Vanuatu. Vanuatu had openly criticised the alleged human rights violations in West Papua and asked United Nations member states to help the people there. Now, Indonesia and Vanuatu have a strained relationship.

Thus, countries that openly criticise the conflicts in Papua without passing through bilateral communication with Indonesia may risk their warm relations with Jakarta.

Australia can convey any concerns with Indonesia’s domestic political issues directly through its ambassador in Jakarta. This is not only about respecting one another’s national sovereignty, but more importantly about maintaining warm ties between Jakarta and Canberra.

On the other hand, with assistance from Australia, Indonesia can expect a chance to exert more influence in the South Pacific, which is vital to maintain stability in Papua.

Indonesia can also urge Australia to persuade its close ally, the US, to attend the G20 Summit in Bali this November – with or without Russian President Vladimir Putin’s presence – and help create a conducive situation ahead of the high-level meeting.

The US is among several western countries that pledged to boycott the G20 summit if Putin attends.

Australia and the US share interests in Southeast Asia and South Pacific and, historically, are primarily on the same camp in responding to global conflicts. Thus, Australia may have the power to convince the US that boycotting the talks will disadvantage efforts to boost Western influence against China in Southeast Asia.

The next question could be: why is the presence of all G20 leaders important for Indonesia?

Their attendance will signify the success of Indonesia in the G20 presidency. This is essential for, at least, President Jokowi personally, as he will be able to create a memorable legacy before leaving the office in 2024.

Yohanes Ivan Adi Kristianto does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.