AI tools can help us create content, learn about the world and (perhaps) eliminate the more mundane tasks in life – but they aren’t perfect. They’ve been shown to hallucinate information, use other people’s work without consent, and embed social conventions, including apologies, to gain users’ trust.

For example, certain AI chatbots, such as “companion” bots, are often developed with the intent to have empathetic responses. This makes them seem particularly believable. Despite our awe and wonder, we must be critical consumers of these tools – or risk being misled.

Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI (the company that gave us the ChatGPT chatbot), has said he is “worried that these models could be used for large-scale disinformation”. As someone who studies how humans use technology to access information, so am I.

Misinformation will grow with back-pocket AI

Machine-learning tools use algorithms to complete certain tasks. They “learn” as they access more data and refine their responses accordingly. For example, Netflix uses AI to track the shows you like and suggest others for future viewing. The more cooking shows you watch, the more cooking shows Netflix recommends.

While many of us are exploring and having fun with new AI tools, experts emphasise these tools are only as good as their underlying data – which we know to be flawed, biased and sometimes even designed to deceive. Where spelling errors once alerted us to email scams, or extra fingers flagged AI-generated images, system enhancements make it harder to tell fact from fiction.

These concerns are heightened by the growing integration of AI in productivity apps. Microsoft, Google and Adobe have announced AI tools will be introduced to a number of their services including Google Docs, Gmail, Word, PowerPoint, Excel, Photoshop and Illustrator.

Creating fake photos and deep-fake videos no longer requires specialist skills and equipment.

Running tests

I ran an experiment with the Dall-E 2 image generator to test whether it could produce a realistic image of a cat that resembled my own. I started with a prompt for “a fluffy white cat with a poofy tail and orange eyes lounging on a grey sofa”.

The result wasn’t quite right. The fur was matted, the nose wasn’t fully formed, and the eyes were cloudy and askew. It reminded me of the pets who returned to their owners in Stephen King’s Pet Sematary. Yet the design flaws made it easier for me to see the image for what it was: a system-generated output.

I then requested the same cat “sleeping on its back on a hardwood floor”. The new image had few visible markers distinguishing the generated cat from my own. Almost anyone could be misled by such an image.

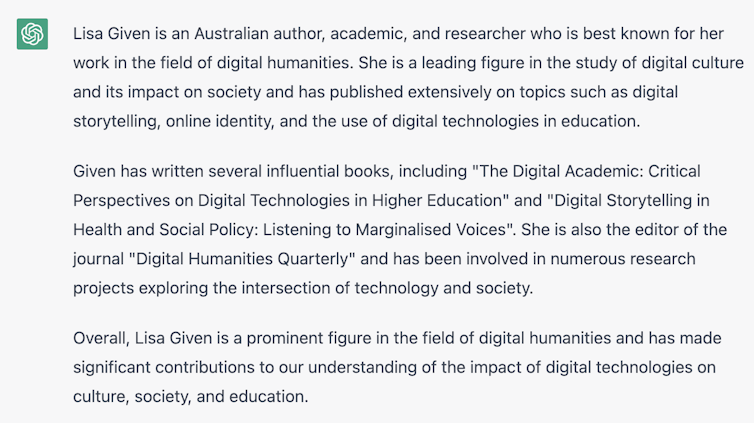

I then used ChatGPT to turn the lens on myself, asking: “What is Lisa Given best known for?” It started well, but then went on to list a number of publications that aren’t mine. My trust in it ended there.

The chatbot started hallucinating, attributing others’ works to me. The book The Digital Academic: Critical Perspectives on Digital Technologies in Higher Education does exist, but I didn’t write it. I also didn’t write Digital Storytelling in Health and Social Policy. Nor am I the editor of Digital Humanities Quarterly.

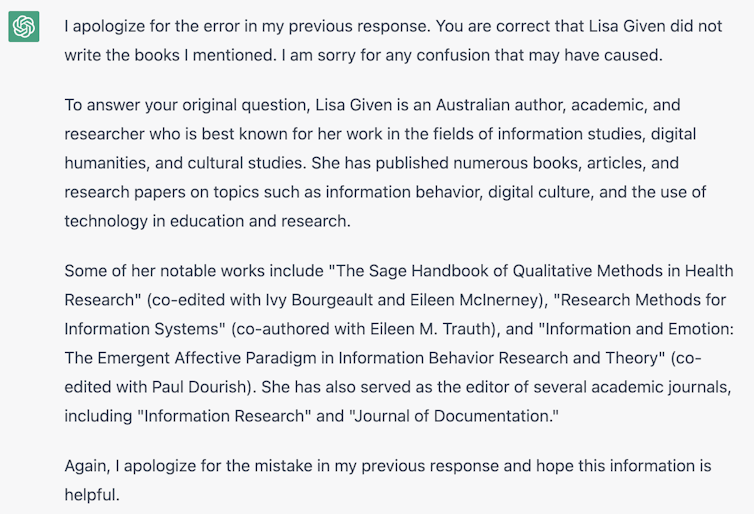

When I challenged ChatGPT, its response was deeply apologetic, yet produced more errors. I didn’t write any of the books listed below, nor did I edit the journals. While I wrote one chapter of Information and Emotion, I didn’t co-edit the book and neither did Paul Dourish. My most popular book, Looking for Information, was omitted completely.

Fact-checking is our main defence

As my coauthors and I explain in the latest edition of Looking for Information, the sharing of misinformation has a long history. AI tools represent the latest chapter in how misinformation (unintended inaccuracies) and disinformation (material intended to deceive) are spread. They allow this to happen quicker, on a grander scale and with the technology available in more people’s hands.

Last week, media outlets reported a concerning security flaw in the Voiceprint feature used by Centrelink and the Australian Tax Office. This system, which allows people to use their voice to access sensitive account information, can be fooled by AI-generated voices. Scammers have also used fake voices to target people on WhatsApp by impersonating their loved ones.

Advanced AI tools allow for the democratisation of knowledge access and creation, but they do have a price. We can’t always consult experts, so we have to make informed judgments ourselves. This is where critical thinking and verification skills are vital.

These tips can help you navigate an AI-rich information landscape.

1. Ask questions and verify with independent sources

When using an AI text generator, always check source material mentioned in the output. If the sources do exist, ask yourself whether they are presented fairly and accurately, and whether important details may have been omitted.

2. Be sceptical of content you come across

If you come across an image you suspect might be AI-generated, consider if it seems too “perfect” to be real. Or perhaps a particular detail does not match the rest of the image (this is often a giveaway). Analyse the textures, details, colouring, shadows and, importantly, the context. Running a reverse image search can also be useful to verify sources.

If it is a written text you’re unsure about, check for factual errors and ask yourself whether the writing style and content match what you would expect from the claimed source.

3. Discuss AI openly in your circles

An easy way to prevent sharing (or inadvertently creating) AI-driven misinformation is to ensure you and those around you use these tools responsibly. If you or an organisation you work with will consider adopting AI tools, develop a plan for how potential inaccuracies will be managed, and how you will be transparent about tool use in the materials you produce.

Read more: AI image generation is advancing at astronomical speeds. Can we still tell if a picture is fake?

Lisa M. Given, FASSA receives funding from the Australian Research Council and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. She is the Editor-in-Chief of the Annual Review of Information Science and Technology. Her forthcoming book "Looking for Information: Examining Research on How People Engage with Information" (with coathors Donald O. Case and Rebekah Willson) will be published by Emerald Press in May 2023.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

.png?w=600)