The debate about generative AI in architecture and creativity as a whole looks set to rumble on for perpetuity. Creators are divided into two camps; AI is either a tool like any other, or it is an existential threat that looks set to unravel the intangible magic of human creativity. Architecture might consider itself the mother of the Arts, but it is an intractable morass of disciplines and data. Could AI tools offer a path through the complexities of modern construction without sacrificing the visual expressionism of architectural design?

Founded by the late Zaha Hadid in 1980, ZHA has always been a pioneer in computer-aided design. Wallpaper* spoke to the studio’s Associate Director Shajay Bhooshan, a co-founder of CODE, the studio’s Computational Design Research Group, along with Lead Designer and CODE colleague Vishu Bhooshan and ZHA Director Nils Fischer, who has been at the firm for 20 years. How have machine learning, AI and CAD evolved and intersected over the years?

AI in architecture: what does the future look like?

‘We’ve done machine learning for many years for floorplate optimisation,’ says Fischer, ‘it’s what many people would consider AI.’ The studio was quick to explore the potential of early generative software, notably DALL·E, OpenAI’s text-to-image model first released in January 2021. ‘We were as excited as everyone else,’ says Fischer, ‘we’re not frightened of breaking things.’

As Instagram’s most popular architecture firm with 1.4m followers, ZHA had a massive visual archive, both public and private. One of the first AI experiments the studio undertook was to upload this dataset into Stable Diffusion, another generative artificial intelligence model. ‘Our team has been curating data sets and training models,’ Fischer explains, ‘[but they] are like a five-year-old child – they have fantastic dreams but not what you actually need.’

AI has proved an effective ‘quick and dirty’ way of creating renders and visualisations, without making any impact on the design process. As Fischer says, ‘Midjourney will not solve the issues of construction and programme.’ ‘General purpose AIs are particularly bad at understanding the interface of elements,’ he continues, ‘they have a pseudo-understanding of construction.’

While this is true of all LLMs and the way they respond to cues and questions, ZHA is committed to building tools that exploit the strengths of AI, rather than the illusions that paper over its weaknesses. ‘I think the next big thing in architecture is using language models,’ says Fischer, ‘like in coding.’ ZHA’s CAD programme of choice is Autodesk Maya, a modelling package that had its origins in cinema and animation. ‘You could theoretically use Maya data to train an AI, like a code repository,’ says Fischer, ‘[if you] create a codifiable design language for architecture, it doesn’t matter what you design – you have a language.’

What stops this kind of repository becoming practical is the vast complexity of a building. ‘The investment in detail outweighs the benefits,’ Fischer explains, ‘in automotive and aerospace you have design and fabrication under one roof – the IP is all in one bucket. Liabilities are different in construction.’

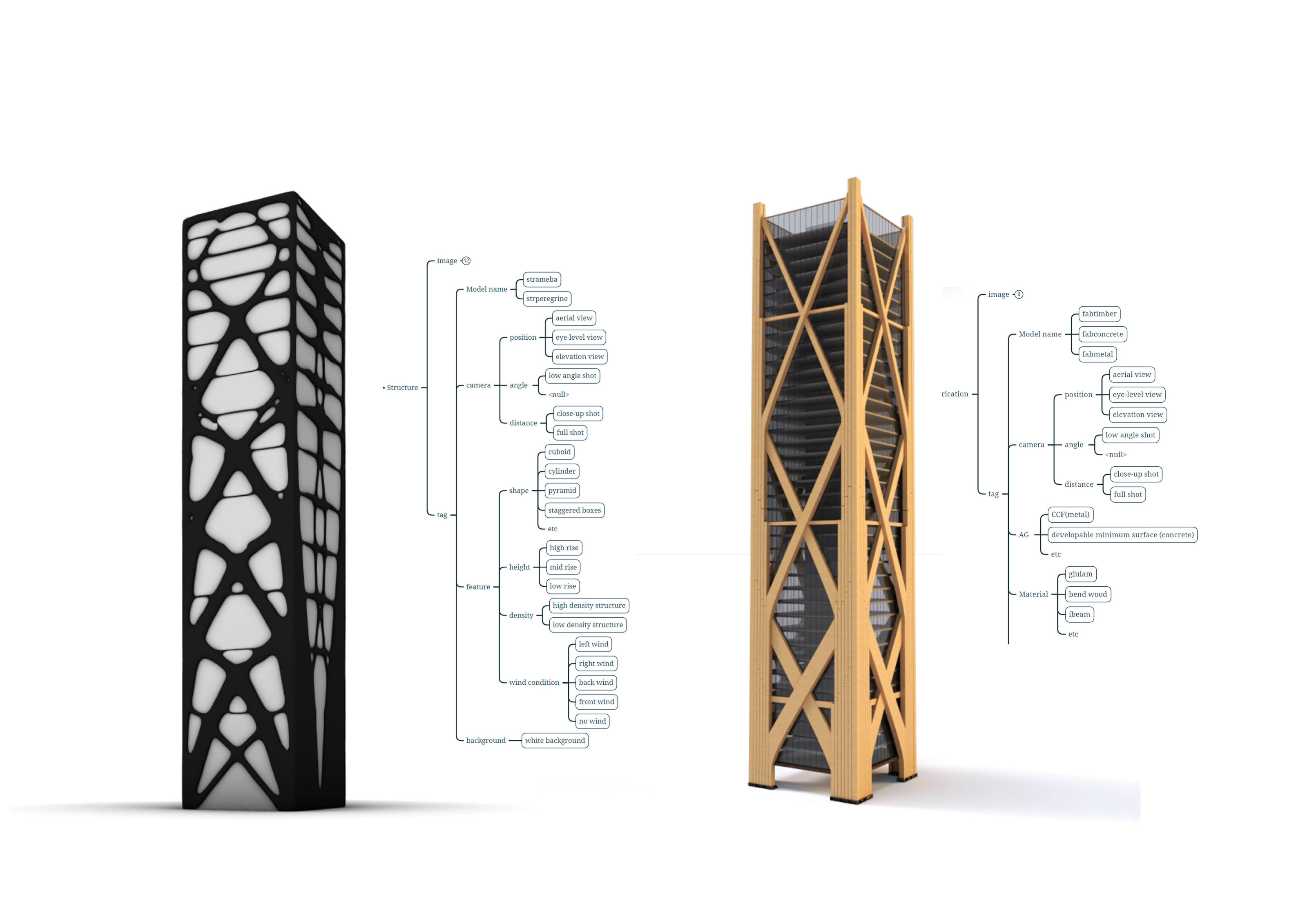

So how has ZHA’s use of AI progressed? According to Shajay Bhooshan, the gulf between the two-dimensional image and the three-dimensional model are still huge. ‘Images are a unified format – there are billions of them. They align with the way computer hardware works. 3D is different,’ he says, ‘those prerequisites are not there.’ Ultimately, ZHA is seeking to create a ‘prototype unified file format that would be the 3D equivalent of an image,’ something that could be used to train a generative AI.

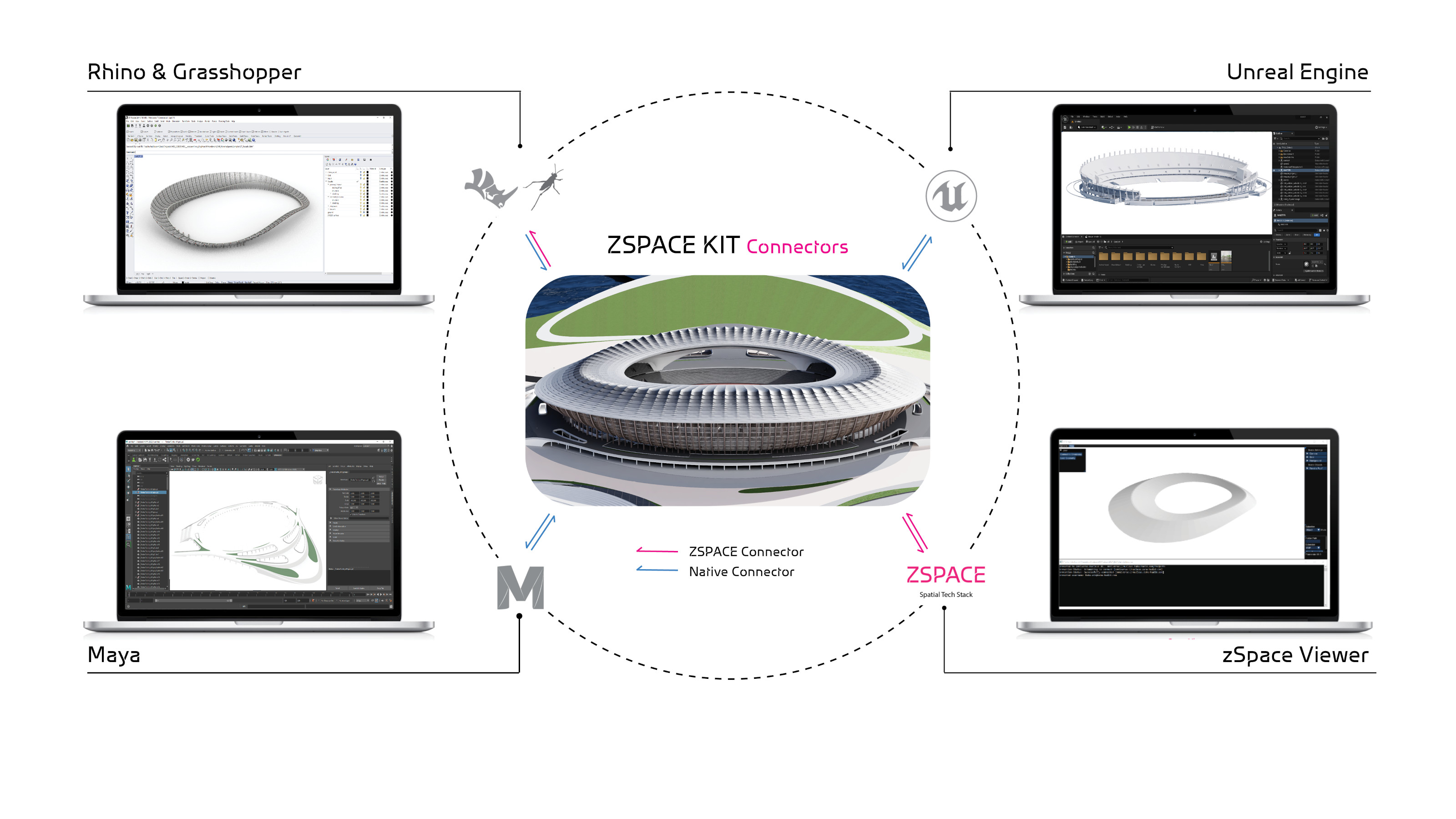

ZHA is using NVIDIA’s Omniverse Platform, a modelling toolkit that speeds up the integration of 3D models with design, rendering and presentation tools, as part of its ZSPACE kit. For manufacturing, the idea of creating a ‘digital twin’ of a product or factory is standard practice. Architecture is a bit more esoteric and specialised. Vishu Bhooshan explains the NVIDIA tie-in as being ‘about getting various stakeholders to collaborate in the same file format.’ ‘It’s very rare for architecture companies to have this information available in an accessible way,’ Shajay adds.

All of this work requires number crunching on an unprecedented scale. ZHA uses NVIDIA-powered workstations containing its latest GPUs (graphical processing units), using off-the-shelf software like Unreal Engine in addition to specialist CAD programmes to create real-time visualisation as well as more complex data-heavy models. NVIDIA, which recently surpassed Apple as the world's most valuable company, focuses mainly on industries like manufacturing and automotive, not comparatively small sectors like architecture. However, through its collaboration with ZHA, Omniverse’s abilities have expanded.

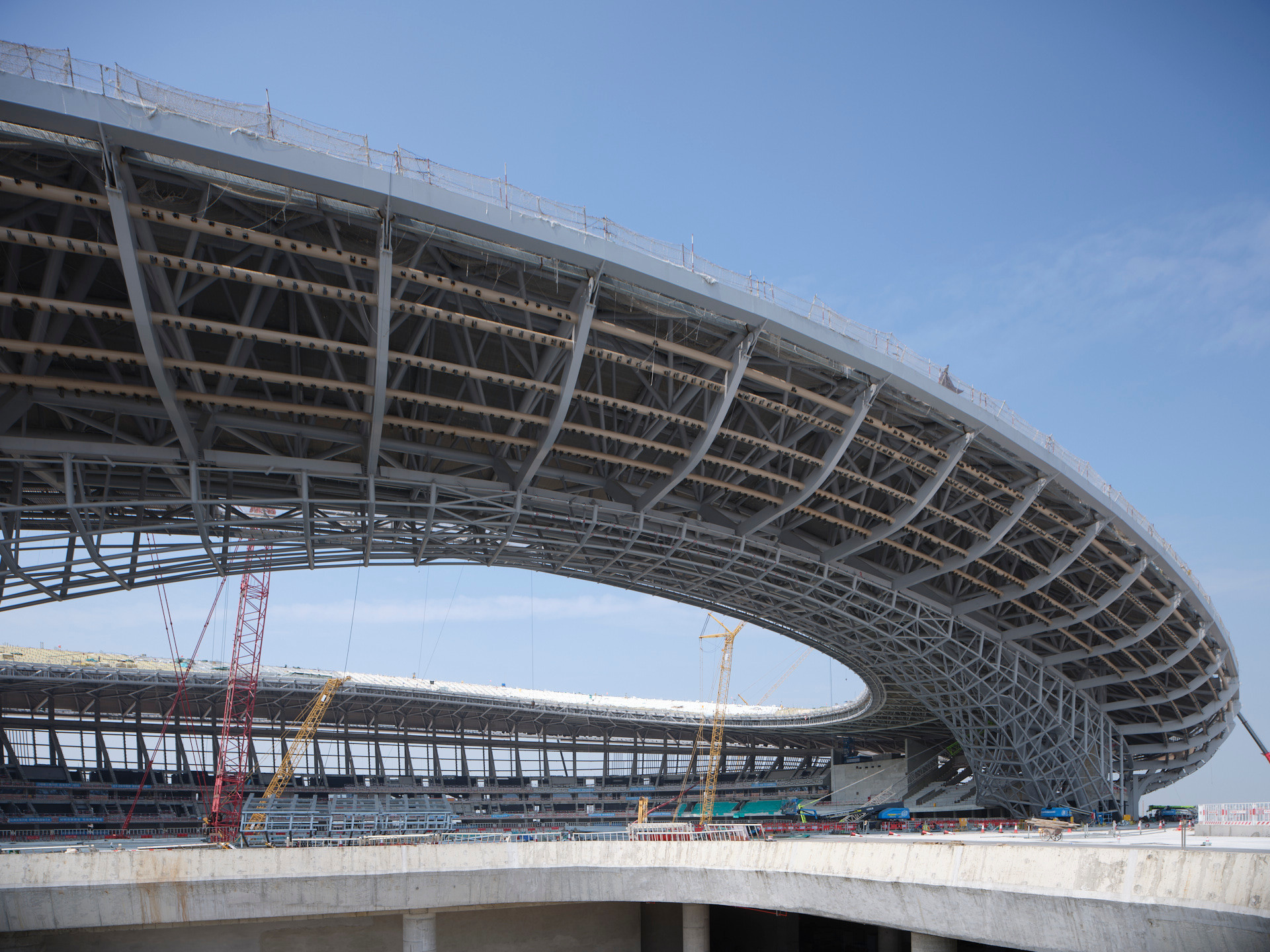

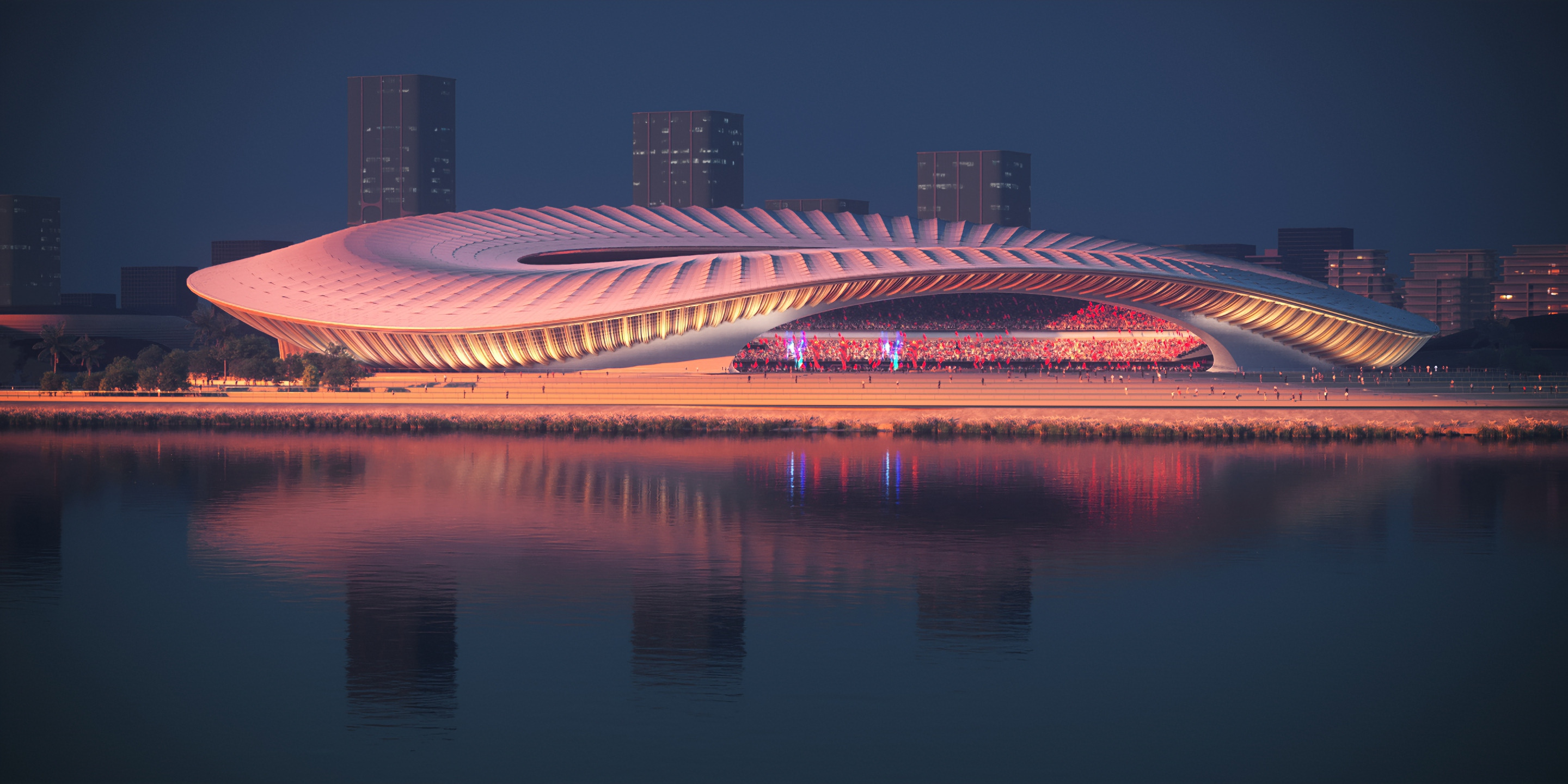

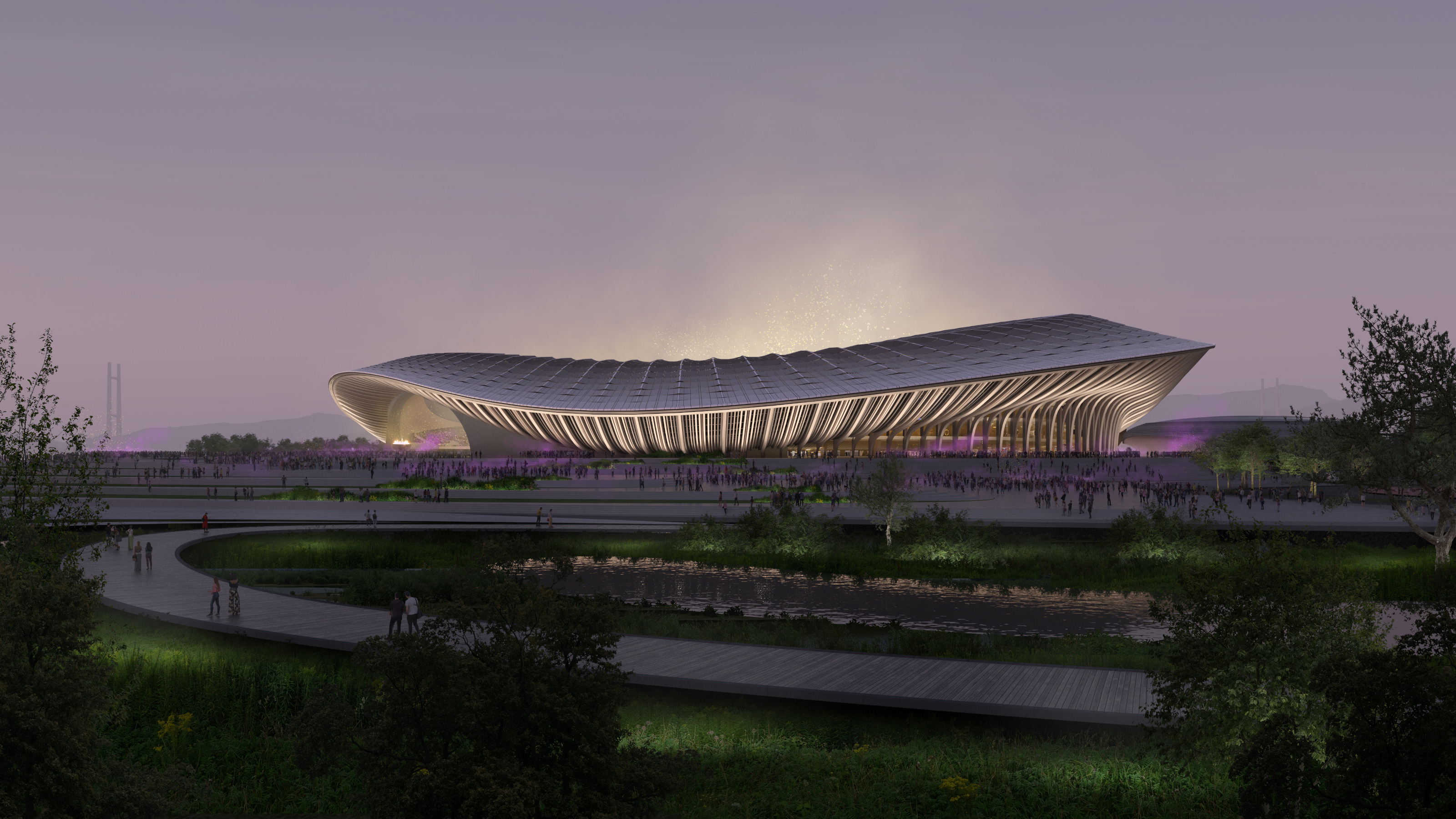

The first physical application of the tools is on ZHA’s Nansha Sports Complex in Guangzhou, a 60,000-capacity stadium that is currently under construction. The project uses the Omniverse Platform to unite the previously incompatible suites of software used to create the geometry, form and visualisations of the complex. Previously, all of this data had to be manually compiled and cross-checked, interchanged between 3D packages like Maya and McNeel Rhino3D. NVIDIA’s tool unites these datasets using OpenUSD, an open-source version of Pixar’s Universal Scene Description framework, originally developed for animation.

The creation of these vast, ‘clean’ 3D models also has huge implications for AI, going far beyond the 2D applications of generative AI. Instead, the 3D data that is created will allow the next generation LLMs to propose 3D architectural forms, informed by the datasets and parameters of each site. ‘If you give an AI a virtual world it can learn the latent relationships in that world,’ Shajay Bhooshan says, explaining how current AI models are ‘an abstraction of a neural network. It’s clearly not the human brain, but it’s useful because it gives us an insight into how we can make decisions.’

In terms of shaping buildings, this allows ZHA to apply ‘point generating elements’ to their designs, things like better transit, more daylight, low energy, etc. ‘Architecture doesn’t really invest in research,’ he adds, ‘this is a rising tide that will lift everybody’s boats. These tools have a value that isn’t determined yet.’

ZHA is already dipping its toes in virtual worlds, using Fortnite to set up a series of modular architectural elements that could be added to the game world as a means of testing out a form of generative urbanism. As well as the Fortnite collaboration, recent ZHA projects have included work with artist Refik Anadol, as well as an ongoing focus on small, experimental projects like pavilions. Describing them as ‘sculptor’s maquettes’ and technology demonstrators, these small structures have been an essential part of the studio’s output since the earliest days.

Fischer describes AI as a ‘toolset change’, adding that ‘it’ll become part of the profession. You’ll be looking at a number of niche tools that solve very specific problems.’ These could be sustainability uses that take a 3D model to create a lifecycle carbon assessment, for example. ZHA was a pioneer in parametric design, creating models that automatically adjusted according to design variations. Using an AI to process the dataset allows near instant feedback on things like wind studies, energy use, etc., as well as explore myriad visual opportunities for a site.

‘Our investment in AI is to improve our own speed of iteration. We don’t do a lot of buildings, but we do a lot of competitions,’ Shajay continues, ‘AI is a co-pilot or assistant to help complete things, and to make parametric design more accessible to people.’ The ability to render up views in real-time has also transformed client presentations. ‘It helps them participate in their own building,’ he adds, ‘AI has completely changed the art of rendering.’

The architects describe this ability to simultaneously model and get feedback as like working in ‘digital clay’. Noting that many developers already use a form of AI to shape a structure to the limitations of a site, lighting, planning, massing and potential occupation, ZHA is arguing for a more considered, deeper application of this technology. As Fischer notes, ‘most of our cities happen without architecture – look at the coast between Hangzhou and Shenzhen, where 40 million people live. In 20 years, we’ll need cities for 600 million people just to match population projections.’ ‘One of the key roles AI will play in our industry is to democratise design, which will be a good thing,’ says Shajay Bhooshan.

The idea that complex buildings using the fluid, sculptural forms associated with the studio – and with Zaha’s own artistry and practice – could be generated by a set of parameters is unnerving. However, ZHA are quick to point out that they provide a premium product, innovating through public buildings like stadiums, galleries and transport interchanges. ‘We’re a top tier practice because we never do anything twice,’ says Fischer, ‘our AI toolkit will help us do that. Construction is not rocket science, but pretty much every building is a prototype,’ he adds, ‘AI can overcome the inherent inefficiencies in the construction market.’

ZHA’s team is not concerned with AI tools accelerating a race to the bottom. Shajay Bhooshan quotes ZHA principal Patrik Schumacher. ‘He says ‘aesthetics is the promise of performance.’ We know how to turn that into reality.’ Elevate the standard at the top, and you raise everyone else’s game. ‘When Corb came to India he designed seminal buildings in places like Chandigarh, but this also improved the lowest common denominator,’ he explains.

ZHA believes the Nansha Stadium could be considered as ‘project zero’ of AI in architecture, a first step towards a new era of computational design that will have broad implications for architecture and urbanism all over the world.