Sometimes AI-generated imagery is obvious. An impossibly ‘perfect’ man or woman rammed so far up the uncanny valley that they look like a Polar Express pre-render destined for the cutting room. And sometimes it’s not. I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve marveled at a landscape or architectural ‘photography’ Instagram profile, only to be hit with the realization, later, that it was AI-generated.

Now, I’m not a complete AI skeptic. I think the technology has unfathomable potential, particularly in the fields of medicine and science. And I certainly don't look down on the creativity of the medium – there are some incredible AI artists out there. But I am skeptical about how society chooses to use it. Without getting too philosophical – not that I’m in any danger by quoting Conan the Barbarian (1982) – ”What is steel compared to the hand that wields it?”

AI’s relationship with the media has proven problematic, to say the least. Data scraping has prompted privacy and copyright hysteria, and AI-generated words, videos and pictures have only fuelled the fires of fake news. If the worst-case scenario is to be believed, the misuse of AI could pose a threat to both journalism’s purported position as the fourth estate and even the very fabric of democracy.

But my concerns – at least in this article – are comparatively twee. How will AI affect our perception of imagery in the long term?

Any question regarding AI is a burning one, because the technology is moving so darn fast. Artificial intelligence is nothing new, but its advancement and shift to the fore, in just a couple of years, is unparalleled.

Before 2023, it was largely the preserve of sci-fi storytelling and beardy tech journals, a middling bullet point lost in a software or hardware press release. It’s easy to forget how suddenly it became an accessible tool for the masses, a marketing buzzword, a technological milestone, and a prospective force for both good and evil.

But the threat to the photo and video industry has arguably been more instant and apparent than most. At once, AI-generated imagery began dismantling the photograph’s integrity, sidling its way into photography competitions, popping up in commercials – in place of hand-crafted images or videos – and who can forget Adobe’s AI terms and conditions furor?

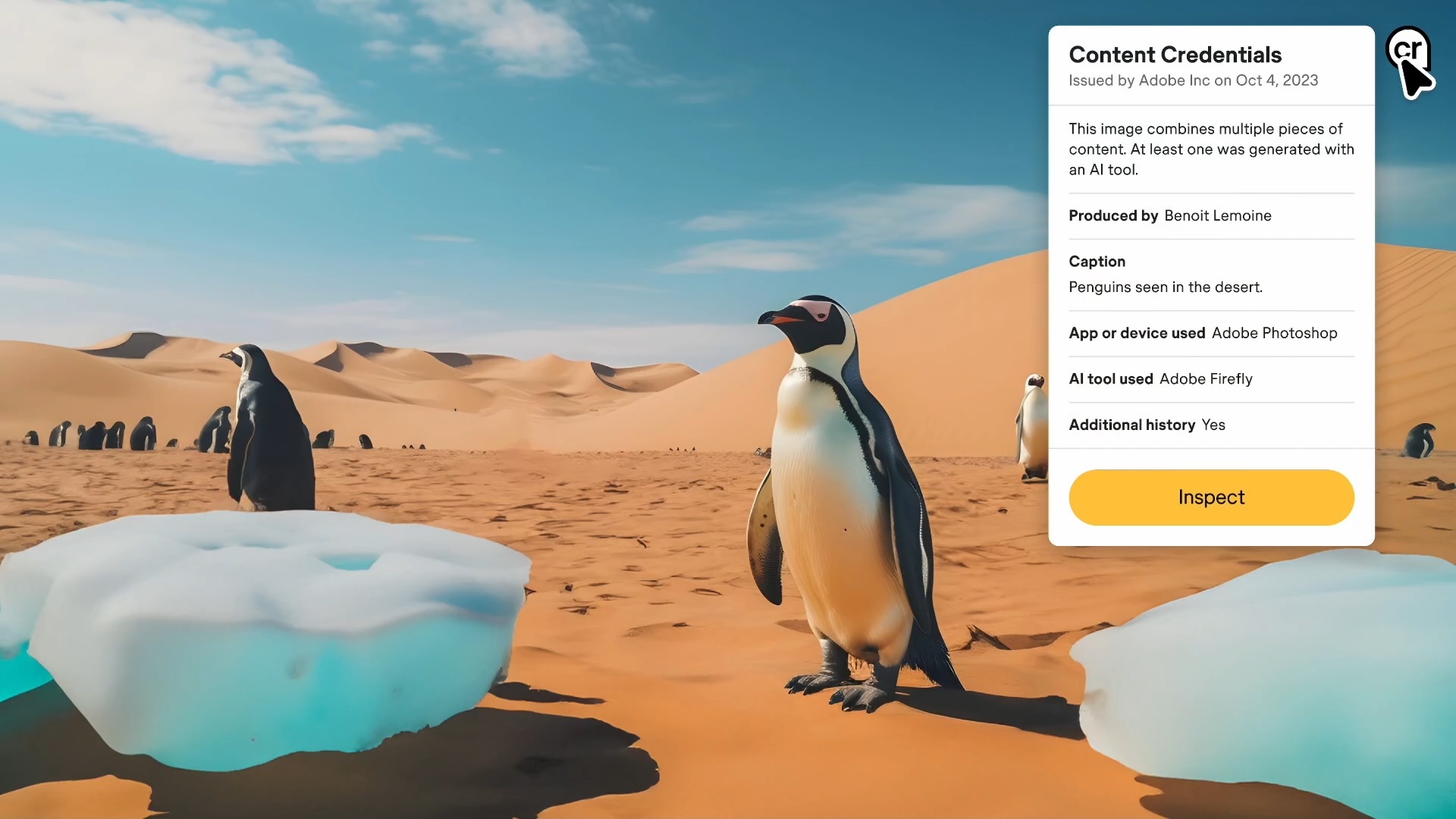

And yet, most detractors have focused their attention on issues of AI-image transparency. A quest to retain the validity of genuine photography, video footage and digital artworks. One solution is the emergence of Content Credentials, the industry’s play to safeguard original content. As well as Google’s SynthID, built to watermark its own Gemini AI creations.

Let’s say that tech industries and governments work together to achieve full AI transparency. There’s another problem. And that’s how AI changes our relationship with the imagery we consume. And this, I feel, isn’t being talked about enough.

The fact is, a lot of AI imagery has an attractive quality to it. You need look no further than the raft of AI-generated Super Panavision 70 videos (spearheaded by creators like AI FlickNips) that have garnered millions of views on YouTube.

You'll soon realize that, for every AI-generated monstrosity that gives viewers the uncanny valley heebie-jeebies, there’s a male lead – unobtainable biceps, oiled and rippling – and a female lead – distorted into an impossible hourglass figure – that viewers struggle to look away from.

These AI fabrications are the human equivalent of a pristine iPhone, slipped from its box milliseconds after the plastic screen protector’s been removed. Organic, they are not. And yet, that's what they purport to be.

And landscapes fare no better. Otherworldly vistas with once-in-a-lifetime sunsets that stretch perfectly across the sky, bathing the scene in liquid golden light. Pockets of mist – the perfect, cinematic consistency – evenly smattered throughout the frame. Unachievable streaks of ice-blue water flowing along idealized streams and rivers. And retina-burning colors, so vibrant and punchy, the finest day in Honolulu would seem drab in comparison.

The A-ayes have it…

My worry, then, is that we’re growing accustomed to these unrealistic visions of the world around us. And the more AI imagery is used, the more genuine portraits and landscapes will seem like relics of a distant past – a Seventies photo album gathering dust beneath a bed. And I don’t see a way to stem this flow of unrealistic imagery, either. You could argue that the AI imagery I've described has been achievable using CGI and digital artistry for years, and you'd be right.

But the problem with AI isn't necessarily the imagery that it creates, it's the prevalence of that imagery. Hand-crafted digital artwork is much more time-consuming and expensive. You need look no further than the film industry's usage of CGI and green screen over practical effects and locations to realize that so long as it’s cheap, the uncanny valley is a price we’re all too willing to pay.

Some may retort that old movies and photographs are still highly regarded, and practical effects are still seen to trump CGI in many cases. And what about the film photography resurgence and black-and-white photography, which never went out of style?

All valid points, but I’d argue that most people have become accustomed to the fabricated sheen of movies drizzled in CGI and green screen, and that much of the retrospective love for yesteryear is fuelled by nerd culture and movie buffs – not the masses.

Just yesterday I read a Telegraph article highlighting Netflix’s apparent disregard for old movies, 1973’s The Sting currently being the oldest film available for UK streamers (at the time of writing). And while film photography is indeed very popular, it’s still extremely niche in the grand scheme of things.

Besides, it’s aesthetics that fuel nostalgia – think film-style photography presets, vintage-clothed models photographed in high resolution and modern throwbacks à la Stranger Things – as opposed to genuine film photographs, old camera equipment and old movies. I will concede that black-and-white photography is an outlier, but then again, color still reigns supreme – and mono has become more of a stylistic choice as opposed to a purely retro indicator.

Sadly, I’ve yet to come up with an answer. For now, all we can do is continue taking real photos, capturing real video, and educating the next generation of photographers and filmmakers. But I fear the lure of cheap AI image generation will ultimately prove too great.

You may also like...

If you're into AI-generated imagery then check out the best AI image generators. If you're a photography purist interested in the latest cutting-edge tech, check out the best professional cameras. And if all this talk of nostalgia has whetted your appetite for retro gear, take a look at the best film cameras.