Shanquella Robinson’s violent death in a luxury rental apartment in Baja California, Mexico, in October is being investigated as a femicide, as prosecutors believe her killing occurred due to her gender.

Robinson’s vacation companions initially told her parents Bernard and Salamondra she had died of alcohol poisoning and refused to seek medical help, prosecutors say.

An autopsy later revealed she had suffered a broken neck minutes before her death.

Femicide is not recognised as a crime in the United States, despite being used in more than a dozen countries across Latin America and beyond to highlight what the World Health Organsiation describes as the “intentional murder of women because they are women”.

Experts say the failure to prosecute femicides under a separate statute is masking an epidemic of violence against US women.

“If we don’t use the vocabulary of femicide, we end up treating these crimes as one-offs,” Dabney Evans, director of the Center of Humanitarian Emergencies at Emory University in Atlanta, tells The Independent.

“We think, ‘Oh it was just this one guy who was a bad apple’, instead of looking at the systemic connections here which are the culture of violence, the culture of toxic masculinity, that arise from misogynistic and patriarchal power structures.”

Not only is gender-based violence not commonly viewed as an aggravating factor under US law, there are few accurate figures available.

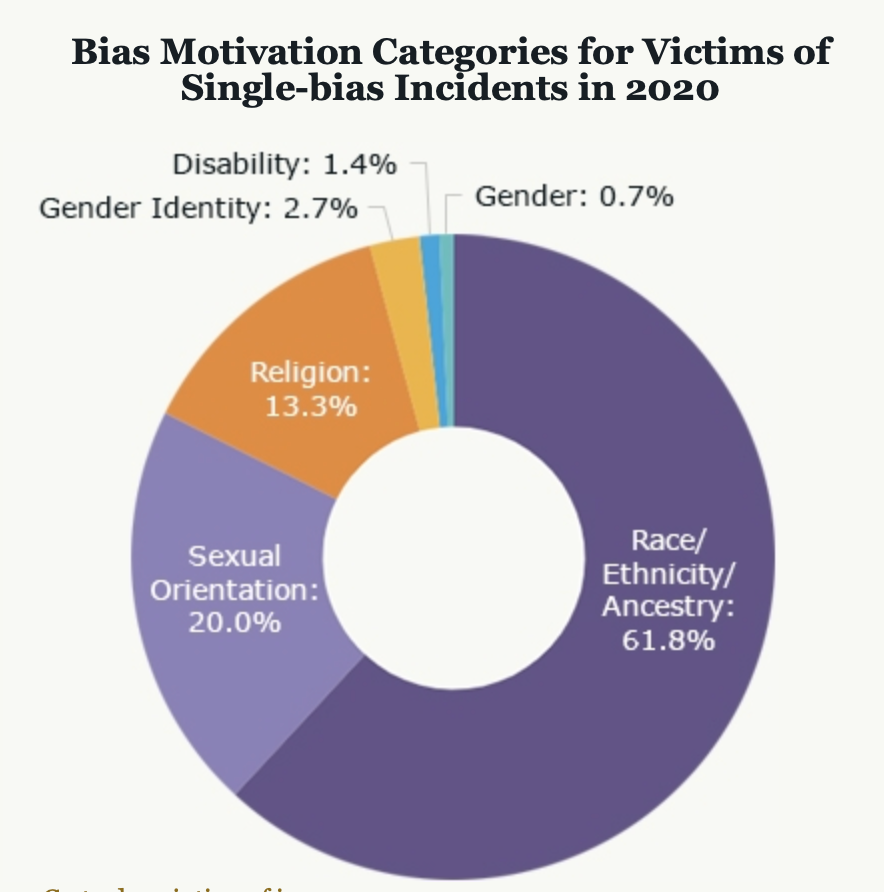

Federal hate crime records monitor violent acts based on religion, race, sexual orientation disability and gender.

But according to the latest figures from the Department of Justice, just 0.7 per cent of the 8,052 hate crimes recorded in 2020 were committed because of gender.

“That’s utterly ridiculous,” says Ms Evans.

“That number is woefully inaccurate in capturing female homicides that may be gender-related.”

‘Oftentimes it is the husband’

Femicide broadly falls under two categories — intimate and non-intimate. The killing of women by their current or former partner is by far the most prevalent.

Among the network of non-profit groups who track violence against women is Everytown for Gun Safety, which says that 70 American women are murdered with a firearm by an intimate partner every month.

A separate analysis by the Violence Policy Center found that 89 per cent of the more than 2,000 women who were murderered by men in 2020 knew their offenders.

“You can think about just about any high-profile crime against women, and oftentimes it is the husband or the boyfriend or the partner who is the perpetrator,” says Ms Evans, citing high-profile cases such as Nicole Brown Simpson, the ex-wife of OJ Simpson, and Laci Peterson, whose husband Scott was convicted of her murder.

In March, Joe Biden signed the reauthorisation of the Violence Against Women Act which expanded protection and support to female survivors of stalking, sexual assault and domestic violence.

“We’re giving survivors real resources against abuse now,” Mr Biden said at the time.

The signing was “overdue”, according to Ms Evans, and failed to plug the “boyfriend loophole”, which allows abusive ex-partners and stalkers with previous convictions to access firearms.

Men who commit violence against their partners are disproportionately more likely to go on to harm and kill others, she says.

A global crisis lacking ‘contextual information’

A United Nations report released last month found that more than 81,000 women and girls were intentionally killed in 2021.

Of those, around 45,000 were killed by family members or partners.

Report authors lamented the difficulty in estimating how many of the killings were femicides, as four in ten of the reported deaths had “no contextual information” that would confirm their circumstances.

“While the overwhelming majority of male homicides occur outside the private sphere, for women and girls the most dangerous place is the home.”

Asia recorded the largest number of female victims of homicide, with more than 17,000, while Africa had the greatest proportion per person.

The Americas reported an estimated 7,500 intentional killings of females.

The UN report states that the killing of women showed a noticeable increase at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, when many families were stuck at home during lockdowns.

In Mexico, femicide cases increased by 145 per cent between 2015 and 2019, according to the Los Angeles Times.

High-profile cases such as the April 2022 murder of 18-year-old law student Debanhi Escobar in the Nuevo Leon region ignited frustrations about a lack of progress in prosecuting femicides.

The killing of Escobar, whose body found dumped beside a highway weeks after she disappeared, remains unsolved, like more than 95 per cent of suspected femicides in Mexico, according to experts.

‘A direct aggression’

Shanquella Robinson’s case doesn’t fit the typical femicide designation. The 25-year-old from North Carolina travelled to San Jose del Cabo with six university friends, her father Bernard has said in interviews.

After her death, a sickening video emerged showing her being punched and kicked while naked by another woman.

On 23 November, Baja California Sur state prosecutor Daniel de la Rosa Anaya issued an arrest warrant for an unidentified suspect.

“Actually it wasn’t a quarrel, but instead a direct aggression,” he told MetropoliMX.

Authorities are yet to announce any arrests in the case.

That person’s identity has not yet released, but it has been widely reported as being the woman seen beating her in the viral clip.

Ms Evans told The Independent that the case should place a spotlight on violence against minority women.

“When we think of femicide, most of the cases that spring to mind are white women. However Black, indigenous and women of colour are much more likely to suffer violence.”

Among pregnant Black women in the US, the number one cause of death is intimate partner violence, she said.