Oct. 17 marks the fourth anniversary of Canada’s recreational cannabis legalization. When The Cannabis Act was passed in 2018, Canada became the second country in the world to legalize the sale, possession and non-medical use of cannabis by adults.

Now, four years on, the federal government is reviewing the law to see if it’s meeting Canadians’ needs. Morris Rosenberg, the former deputy minister of justice, will chair an expert panel for that purpose.

Similarly, the Ontario Cannabis Store recently announced a “holistic review” of its pricing. Other provincial and territorial governments should follow these examples and likewise start looking for improvements in their cannabis rules.

The industry’s rapid growth

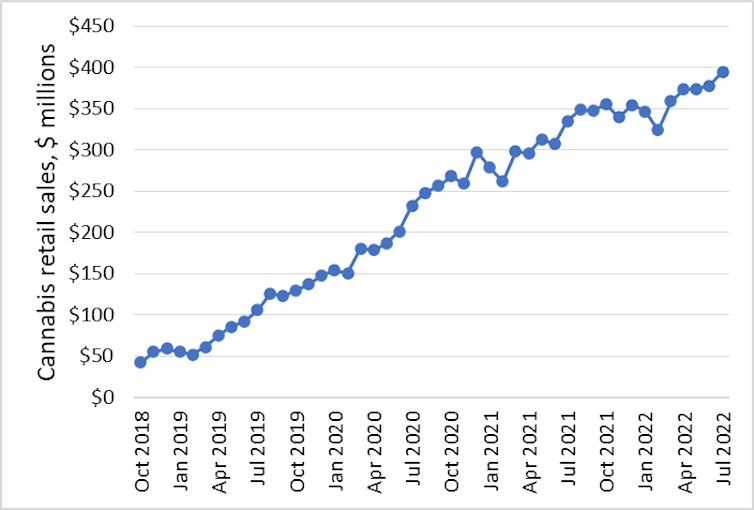

During Canada’s first month with legal recreational cannabis, there were only about 100 licensed stores and sales were just $42 million.

But the industry grew quickly — even the pandemic didn’t slow it down — and Canada now has more than 3,300 licensed stores. Legal cannabis products are more accessible than ever.

Legal products also became more competitive with illegal ones thanks to dry cannabis prices dropping 25 per cent since 2018. In some provinces, they now start at $3.57 per gram including taxes. Improved cannabis product quality has also made those products more competitive with illegal ones.

Consequently, monthly recreational cannabis sales hit $395 million in July, just over half the size of Canada’s beer sales.

However, not all is well with industry. Producers’ profits have suffered due to overproduction. Meanwhile, stores in some places, like Toronto and Manitoba, face too many competitors.

After having little information about the health impacts of cannabis for years, evidence is starting to emerge. A recent study found an increase in cannabis hospitalizations among young children — all the more reason to review cannabis rules.

The federal government’s review only covers things within its jurisdiction, like producers, products and pardons. Since the provinces regulate retailing and consumption, it’s crucial they review their rules too.

Cannabis taxes vary

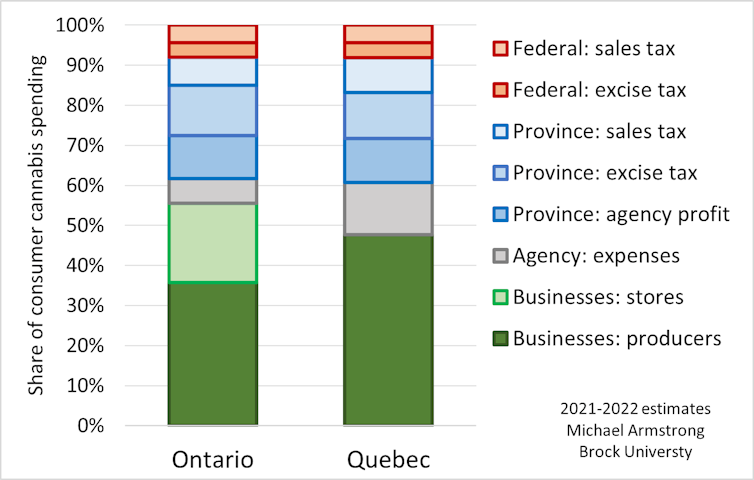

Aside from health-related issues, the provinces should revisit their cannabis rules on taxation. Ontario’s cannabis excise taxes during 2021-22 totalled $215 million, twice that of the year before. Profits at its Ontario Cannabis Store wholesaler, likewise doubled to $184 million. I estimate Ontario also collected about $121 million in sales tax, putting its combined cannabis cash haul at around $520 million.

This means the provincial government received about 30 cents out of every dollar its residents spent on legal recreational cannabis last year. The Ontario Cannabis Store spent another six cents on operating expenses.

By comparison, I estimate the federal government collected a relatively modest eight cents in taxes. That left about 20 cents for retailers and 36 cents for producers. Those businesses spent some of that on government licences, property taxes and income taxes.

Or consider Alberta, which often brags about charging no sales tax but rarely mentions its extra 16.8 per cent cannabis excise tax. That surcharge likely contributed about $74 million of the $164 million Alberta collected in cannabis taxes last year.

Governments clearly need revenue from someplace. But is it appropriate to extract so much from consumers in ways that ignore the industry’s low profitability?

Provincial agency operations

Provinces also should review their cannabis agencies’ operations, including whether those agencies should keep their wholesale monopolies. The Ontario Cannabis Store, for example, collects wholesale markups of about 31 per cent — even on sales it doesn’t touch, when producers sell directly in stores — when just 10 per cent would cover its operating costs.

And as monopolies, the agencies become bottlenecks if they fail. When computer troubles in Ontario and a strike in British Columbia temporarily stopped shipments from cannabis agencies last summer, retailers lost money because they ran out of products. Why not let products flow directly from producers to retailers instead, like Saskatchewan does?

A second issue is whether provincial cannabis agencies have enough stores. Québec’s efficient cannabis agency’s retail-plus-wholesale markup was just 38 per cent, compared to the Ontario Cannabis Store’s 74 per cent. But with fewer stores per capita than other provinces, its legal sales per capita were the lowest. That left more of the market for illegal dealers.

Lastly, provinces should consider simplifying rules to help retailers, without hurting public policy. For example, Alberta recently removed its requirement for stores to cover their windows. Transparent glass can make shops safer for staff inside, and street-friendlier for pedestrians outside.

Store locations are key

Retail density is another key consideration. At one extreme, some Ontario neighbourhoods have too many shops. This clustering occurred partly because the province stalled licensing for a year. The government should make it easier for cannabis businesses to move to underserved areas, thereby reducing the retail hyperconcentration.

Conversely, some rural areas have too few customers to support standalone shops. Newfoundland handles that by letting general stores sell cannabis. Other provinces could consider doing the same thing.

There are also some cities, like Mississauga, Ontario and Richmond, B.C., that have no legal stores because provincial governments let local councils opt out. While it was a smart political move for provinces to allow municipalities to opt out, it might not be a wise policy move.

Learning from experience

As one of the few countries to legalize recreational cannabis, Canada has set an example for others to follow. A growing number of places, including Thailand, Malta, South Africa, Mexico and Germany, are working to implement nationwide legalization.

Even the United States federal government recently took a tiny step toward reforming its conflicted cannabis law patchwork. In the U.S., some states have passed laws authorizing cannabis sales, but they remain illegal at the federal level.

These countries can learn much from Canada’s four years of experience. But Canada’s provincial and territorial governments should learn from that experience as well by reviewing their rules.

Michael J. Armstrong does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.