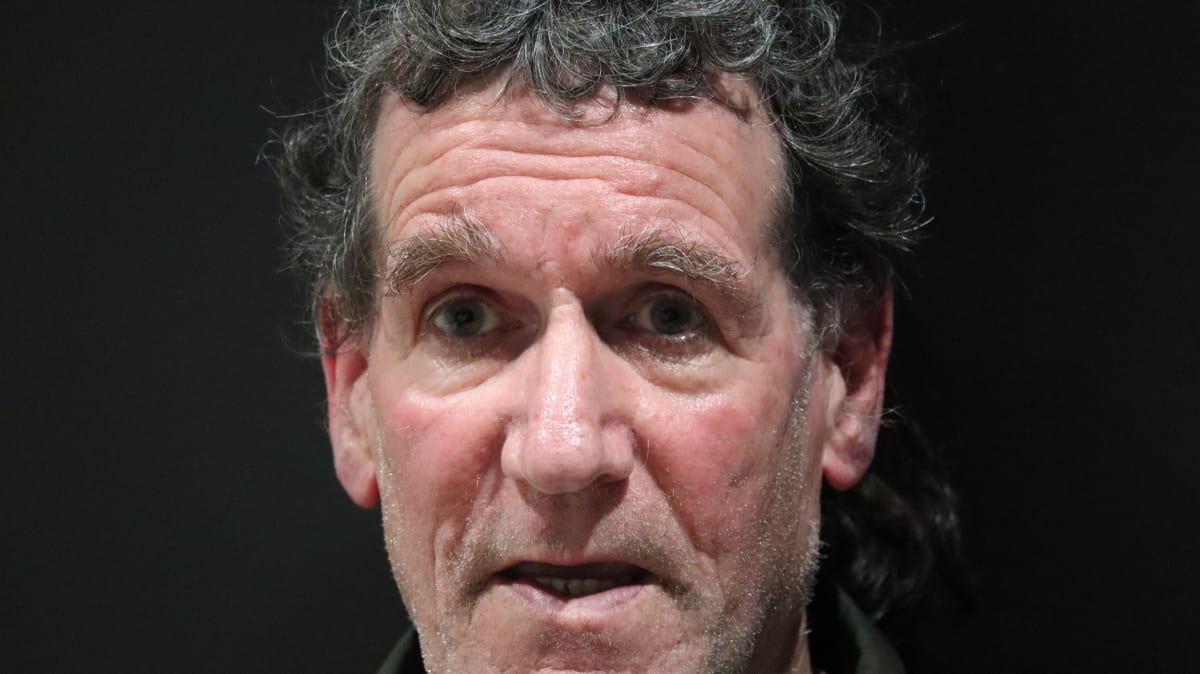

Pressure builds ahead of the country’s top public servant appearing at hearings this week. David Williams reports

Abstract, bureaucratic rubbish. It’s what Keith Wiffin was bracing to hear from government officials giving evidence at the Abuse in Care Royal Commission last week, but it’s still disappointing to hear, and insulting.

Particularly galling for him was the testimony from officials at the Ministry of Social Development, formerly the Department of Social Welfare, the state agency he believes is the main protagonist of abuse in this country.

Wiffin, 62, of Wellington, a survivor of abuse as a state ward, felt the officials’ testimony, last Monday, was arrogant, describing them as a “totally unfeeling, unempathetic group who gave us nothing, really”. Their “insensitive and insulting” response almost brought him to tears.

“I was pretty angry. I had to go for a long walk that night.”

MSD chief executive Debbie Power was presented with a list of perpetrators of sexual, physical, and emotional abuse, spanning decades.

She was asked by commission lawyer Anne Toohey: “Do you agree with me that across a range of institutions, there are individuals who are alleged by survivors to have committed abuse over quite lengthy time periods across a range of institutions nationally throughout New Zealand?”

Power replied: “That’s what the spreadsheet indicates, yes.”

She told the commission the ministry had better policies to tackle complaints.

However, she was confronted with allegations a person still working in a youth justice facility who had 26 allegations of abuse against them, the earliest from 2006.

Asked if this was a major failing, Power responded she wouldn’t say it was a failing, more a situation in which “we didn’t do our best work” which was “hugely unfortunate”.

One particular statement was music to survivors’ ears – the idea of keeping tamariki and rangatahi out of care in the first place.

Much of the officials’ time, however, was spent justifying a controversial new law concerning Oranga Tamariki, which they said would improve oversight and monitoring of children.

“That is hugely disrespectful to survivors, because we don’t think that’s the case,” Wiffin says. “You could have at least acknowledged the serious reservations we have about that because what you’re doing is essentially retaining power and control over the processes and asking us to trust you.”

“Errors is just such an understatement. This was absolutely horrific.” – Paul Gibson

On Tuesday of last week, Police Commissioner Andrew Coster said some survivors received “inadequate service” from the police, which was “difficult to hear”.

Royal Commissioner Paul Gibson’s questioning of Ministry of Health officials last Wednesday is worth quoting at length.

Gibson, a former Disability Rights Commissioner, who is blind, started by acknowledging concessions from officials, and positives, like the creation of Whaikaha, the Ministry of Disabled People. He then called for more genuine acknowledgement of historic abuse.

“Across all the ministries we’ve seen it would be fair to say that the response to the requests to produce from Ministry of Health was by far the least thorough and was actually almost denying of responsibility around historic abuse in care. That doesn’t give me a lot of assurance going forward ... the slowness to learn, the slowness to act, the slowness to take accountability.”

He picked out one particular phrase, used by an official, about not repeating “errors of the past”.

“Errors is just such an understatement. This was absolutely horrific, what happened under the watch of the Ministry of Health and its departments/successive agencies over time: over-medicalisation, developing tools designed to shock and torture people, extreme use of seclusion.”

Ministry of Education officials appeared at the Royal Commission last Thursday. Commissioner Andrew Erueti asked why it wasn’t prepared to accept there was systemic racism in the sector, when Māori were forbidden from speaking te reo Māori.

Secretary of Education Iona Holsted replied: “I’m not saying I don’t accept it. I’m just saying I’m not sure what it means ... because I’m not sure how it takes us anywhere.”

Another notable feature of the hearings was the lack of the word “apology”, and the over-use of “acknowledgements”. Holstead told commissioners she’d spent the night before working on her “acknowledgements”.

The scale of abuse over decades is overwhelming; a damning indictment of state agencies, sometimes working together, which promised to improve the lives of some of our most vulnerable but, instead, dished out the most terrible abuse and torture.

This history, from a system wrapped in racism and discrimination, is well-documented and well-understood, many of them from now notorious institutions. You might have heard the names: Lake Alice, Hokio Beach School, Kohitere Boys Training Centre, and Epuni Boys’ Home, where Wiffin was abused.

Last week marked the first half of a fortnight-long block of hearings at the Royal Commission dubbed the state institutional response.

Wiffin, a member of the Royal Commission’s survivor advisory group, although he’s speaking personally, told Newsroom last Thursday: “What I’ve heard so far is they have been willing to take some responsibility, but they haven’t taken enough responsibility.”

When it did happen, it tended to be when officials couldn’t avoid it. “It is almost begrudging.”

Too much time was taken talking up the improvements that have been made, he says.

Anything that reduces future abuse is welcome, he acknowledges.

“But what I haven’t quite seen enough of is the lens going on what’s happened in the past, what has led to the scale of this tragedy, the scale of the dereliction of duty, the scale of the betrayal, of survivors, and indeed, everyone in this country because of the scale of the impact.”

In 2020, the Royal Commission released research which estimated up to 253,000 people had been abused in care between 1950 and 2019.

It’s easy to believe most families in New Zealand have been affected in some way.

That makes the response of state agencies crucial, not just atoning for their past misdeeds but ensuring this never happens again.

Is abuse still happening today? “Absolutely, 100 percent,” Wiffin says.

“I’m well aware of instances where survivors now have been just as badly treated as we were, from my generation. And in crude terminology, they’ve been told to eff off just like we were.

“So it’s still happening now. Maybe not to the same degree, but don’t try and tell me it’s not happening.”

The first three days of this week’s hearings, held in Auckland and live-streamed, features officials from Oranga Tamariki (Ministry for Children). The hearing will wrap up on Friday with the appearance of the country’s top bureaucrat, Peter Hughes, the Public Service Commissioner.

Wiffin’s story is one of courage and fortitude in the face of ongoing abuse. That is, the abuse allowed by the state, in the first instance, through a lack of monitoring, and then, years later, perpetuated by the state, as it fought, vigorously, against what is known now to be his “meritorous” legal claim.

At age 11, Wiffin was admitted to Epuni Boys’ Home in 1970, following years of his family struggling to cope with the grief of losing his father. His home wasn’t abusive, but Epuni was.

The Royal Commission described it as a “deeply troubled institution with an entrenched culture of abuse”.

Housemaster Alan Moncreif-Wright sexually assaulted Wiffin, repeatedly. He was abused by other staff, physically and psychologically, as well as by other children – sometimes with staff’s encouragement. When he subsequently left for other state institutions, the abuse followed, suggesting a systemic problem.

Wiffin’s struggles spiralled into alcohol and depression, and he was pursued by nightmares. He wasn’t fully educated and his prospects suffered – for income, financial security, personal relationships and health.

In 2006, aged 46, Wiffin lodged a claim for historic abuse in the High Court.

The chief executive of the Ministry of Social Development wrote to him in January 2007, advising it took all claims of abuse and neglect seriously, and assuring him the ministry and Crown Law would be model litigants. The person who signed that letter was Peter Hughes, now the Public Service Commissioner.

Yet, there was no proper investigation, and Crown Law adopted an “adversarial, legalistic and aggressive approach” – despite a Cabinet-approved litigation strategy to settle claims considered meritorious.

The Royal Commission said the most basic of investigations would have turned up evidence corroborating Wiffin’s claims. Moncreif-Wright was a “prolific child-sex offender” who worked in a place giving him unfettered access to vulnerable young boys.

MSD falsely told Wiffin’s lawyer, Sonja Cooper, it didn’t have information about allegations of sexual and physical abuse by Moncreif-Wright.

The Crown made an offer to settle Wiffin’s claim in 2009, which contained no financial compensation, no apology, limited “acknowledgements”, and an offer of counselling up to a maximum sum of $4000. An internal email called it “paltry”, while the Royal Commission described it as a moral failure.

Dejected, Wiffin rejected the offer and discontinued his claim – a “good result”, according to correspondence from Child, Youth and Family to Crown Law.

No one from the Crown had contacted Moncreif-Wright, but, ultimately, police did, after the abuser was confronted by media. Wiffin was a witness in the criminal prosecution and Moncrief-Wright admitted five sexual offences against him while he was at Epuni.

Another twist involves the surveillance of abuse survivors, something Wiffin is convinced happened to him in the lead-up to a test case known as the White Trial, in 2007.

MSD spent $90,000 on private investigators to find information about claimants and witnesses – something it initially denied in 2016, but was found to be true by a later State Services Commission inquiry.

The State Services Commissioner, who now has a slightly adjusted title, was Peter Hughes. And MSD’s chief executive in 2007 was Peter Hughes. The Crown, guilty of withholding information about a known paedophile from a victim of abuse, investigated itself, a constant source of criticism from abuse survivors.

What does Wiffin want from officials this week? Honest and transparency, he says. He mentions Hughes’ appearance on Friday – “that’s what I want from him, most of all.”

Back when Hughes headed MSD, the scale of abuse must have become apparent by the sheer volume of claims, Wiffin believes, making it seemingly obligatory for ministers to be advised of a potentially massive problem.

Yet it was Wiffin’s lobbying of the Labour Party, while in opposition, which helped spark the Royal Commission, questioning the state agencies about their decisions and actions.

Whatever he did when he headed MSD, Hughes now sits at the top of the bureaucratic pyramid, astride a public service that, through many agencies, obstructed legitimate legal claims, intentionally delayed proceedings, and treated abuse survivors with callous indifference and cruelty, re-traumatising them.

Wiffin says: “We have had resistance from all of those government agencies in one form or another over a very long period of time. And he’s [Hughes] been in this role for a long time – long enough to see all that, long enough to know about it.

“What have you done about it?”