Several countries across the African continent are currently embroiled in war. Some of those worst hit are South Sudan, Ethiopia, Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Somalia, the Central African Republic and Burkina Faso. These armed conflicts are caused by a range of factors, including bad governance, corruption, poverty, rights violations and religious intolerance.

Armed conflict has led to the loss of millions of African lives over the decades and negatively affected national development. It has also caused huge losses to cultural heritage.

As a scholar of international law, with a focus on cultural property law, my research and policy briefs have analysed applicable policies and legislation that would protect heritage during conflict.

I have found that without a reawakening of cultural conscience among Africans – and political will from governments – the continent’s heritage will continue to suffer neglect and destruction.

Partnerships among African states, heritage stakeholders, and regional and international organisations are equally fundamental in establishing a solid foundation for heritage protection.

Widespread destruction

There are several accounts of the destruction to Africa’s heritage in conflict situations.

For instance, the war between Eritrea and Ethiopia – which started in 1998 and ended with a peace deal in 2000 – resulted in the Ethiopian army toppling the Stella of Matara, a 2,500-year-old sculpture of cultural significance.

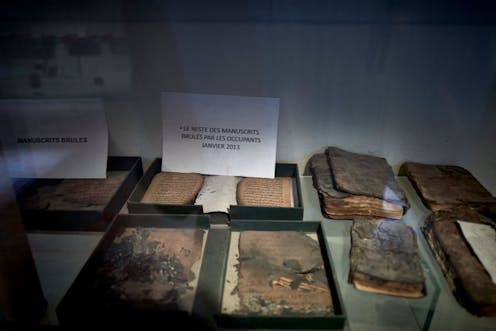

In Mali in 2012, rebel Islamist groups took over Timbuktu and destroyed mosques, mausoleums and Sufi tombs that had been built as far back as the 15th century.

In Côte d'Ivoire, sacred circular masks were stolen and some burnt during a conflict that began in 2002. The Klin Kpli, the sacred talking drum of the Baoule people, was stolen from the royal court of Sakassou.

In Senegal between 1990 and 2011, churches, mosques and sacred forests were destroyed as civilians used them for refuge and combatants sought to hide from government troops.

In the Nigerian civil war between 1967 and 1970, the Oron Museum in the country’s east was occupied by troops. The Oran Kepi ancestral figures kept there were moved to Umuahia town in the south for safekeeping. When the war reached Umuahia, the objects were transferred to Orlu, about 70km away. Unfortunately, a lack of knowledge on the value of these artefacts led to their being used as firewood by the residents of Orlu.

Read more: The ICC's Al-Mahdi ruling protects cultural heritage, but didn't go far enough

In Sierra Leone, the civil war between 1991 and 2002 severely damaged a museum in Freetown. Some artefacts were riddled with bullet holes, while others were destroyed by rain due to the damage done to the museum’s roof, windows and doors.

Ethiopia has more recently illustrated how armed conflict destroys historical items. The country’s northern region of Tigray – rich in religious heritage and a tourist attraction – has been war-torn since November 2020.

Ancient manuscripts and invaluable artefacts in the region have been targeted for destruction and looting by Ethiopian and Eritrean troops.

International treaties

International law provides for the protection of cultural heritage during war. However, for these legal mechanisms to take effect, governments need to have effected them during times of peace.

One such law is the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict. It has Protocols I and II.

Protocol II is the most effective at protecting heritage during conflict. State parties to the protocol can exercise universal jurisdiction to extradite or to try any heritage offenders found in their territory.

Another important law is the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property. There is also the 1995 UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects.

The 1970 UNESCO and 1995 UNIDROIT conventions – if properly implemented by countries – can help prevent the looting and illicit trafficking of cultural property. To implement these conventions, state parties need to, among other things, have up-to-date heritage legislation and inventories of their artefacts.

However, no African country has any laws specifically aimed at domesticating these international conventions. This makes implementation of their provisions largely impossible.

Ethiopia and the treaties

Ethiopia became a state party to the 1954 Hague Convention on 31 August 2015. However, it has not joined the convention’s 1999 Protocol II. This means the country cannot benefit from these provisions.

In 2021, Ethiopia submitted to the 1954 Hague Convention committee a report on its activities under the treaty for the period between 2017 and 2020. The country outlined its implementation of Articles 3, 25 and 28 of the Hague Convention.

Read more: For Africa's people, culture and heritage are a form of liberation

Article 3 covers measures put in place in peacetime to safeguard cultural property against the foreseeable effects of an armed conflict.

Article 25 addresses measures geared towards public enlightenment. This includes training of the military and civilian populations in peacetime on principles that would ensure the protection of cultural property.

Article 28 focuses on putting mechanisms in place nationally for sanctioning nationals and foreigners who violate the convention’s provisions.

Additionally, Ethiopia ratified the 1970 UNESCO Convention in November 2017. Articles 7 and 9 of the convention allow for international cooperation among state parties. This ensures that objects illicitly removed from the territory of a state are returned.

Ethiopia can rely on these provisions and, through diplomatic offices, ensure the return of objects looted during the war.

However, there are reports that Ethiopian forces are behind the destruction and looting of various historical and cultural heritage items in Tigray. This illustrates the gaps in the government’s political will to safeguard the country’s heritage.

Reversing the trend

Misinformation and a shallow understanding of the significance of heritage items are at the root of the violence demonstrated against heritage items in many parts of Africa – and beyond.

To counter these, protecting heritage requires:

political will

civic education on the value of heritage

partnership among African states, heritage stakeholders, and regional and international organisations

strengthening national legislation and harmonising it with international best practices.

Afolasade A. Adewumi does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.