The United States is facing an expanding gap between how much workers earn and how much they have to pay for housing.

Workers have faced stagnant wages for the past 40 years. Yet the cost of rent has steadily increased during that time, with sharp increases of 14% to 40% over the past two years.

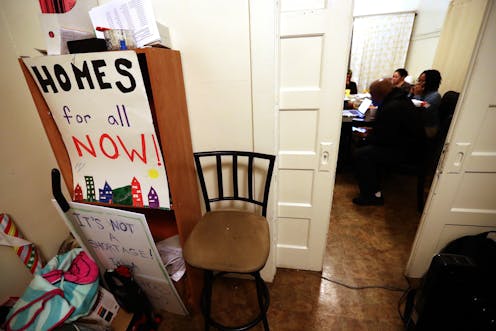

Now, more than ever, workers are feeling the stress of the affordable housing crisis.

While I was conducting research in economically hard-hit communities from Appalachia to Oakland, California, for my recent book, published in November 2021, nearly every person I met was experiencing the painful reality of being caught between virtually stagnant wages and rising housing costs.

As a sociologist, I had expected that low-wage workers would struggle with the cost of housing. I did not expect to meet people who worked two jobs and lived with roommates and still struggled to pay their bills.

For perspective, a person making US$14 an hour would have to work 89 hours a week to cover the rent on a “modest” one-bedroom rental, estimated to cost $1,615 per month, according to a 2021 study by the National Low-Income Housing Coalition.

Millions of workers earn less than $14 an hour. Among U.S. employees, the average hourly earnings, adjusted for inflation, were only $11.22 in 2022.

In January 2022, median rents in the U.S. reached their highest level yet. The average median cost of one-bedroom units in the 50 largest metro areas rose from $1,386 in 2020 to $1,652 in 2022.

‘Now I’m having to scrounge’

I interviewed PL (a pseudonym) for my recent book. He is among the 44 million people in the U.S. who rent their homes.

PL is a longtime Oakland, California, resident, who works full time in a professional career. Despite employment stability, his financial circumstances are worsening.

“Rent is raised dramatically from year to year. I work in a nonprofit organization, so I don’t get a raise every year,” PL told me during an interview in 2018. His monthly rent increased by $250 over the previous three years. Yet his salary remained static.

“That $250 was going toward the grocery bills, the gas bills. Now I’m having to scrounge,” PL said.

PL is not alone.

Households that spend more than 30% of their income on rent are referred to as “cost burdened,” according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. In 2019, 37.1 million households, or 30.2% of all U.S. households, fit this category. The situation has worsened since the pandemic.

The financial burden of the increasing cost of rent falls hardest on the half of workers in the U.S. who earn less than $35,000 each year. After paying rent, about 80% of renter households with incomes under $30,000 have between $360 and $490 left to cover all other expenses, including food, health care, transportation and child care.

Where can you live?

Oakland has been described by gentrification experts as the new center of the nationwide affordable housing crisis.

A growing tech industry in San Francisco, a lack of affordable housing, weak rent control laws and a predominance of low-wage service industry jobs contribute to the shortage of affordable housing in Oakland.

Vanessa Torres is one of the more than 15,000 people who live in a low-income neighborhood in Oakland known as “the Deep East.” When I spoke with Torres in 2020, the worry in her voice was clear.

“This is the ‘hood. If low-income Latinos can’t afford it anymore, well where do we go? If we can no longer afford to live in low-income communities that are considered dangerous, that are considered poor, then where do we see ourselves?” Torres said.

In 2019, the midpoint for monthly rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Oakland was $2,300.

Torres would need to earn almost $50 per hour, approximately $96,000 a year, to be able to afford $2,300 a month in rent, according to the nonprofit California Housing Partnership Corp.. Torres earns roughly $50,000 a year as an educator.

Still seeking solutions

Elected officials across the country have tried to address the affordable housing crisis through proposals to raise the minimum wage and to mandate more meaningful rent control. They have also proposed greater government investment in affordable housing, and pursued partnerships with developers. As yet, none of these efforts has been successful to any significant extent.

Countries with more government control over the economy have taken a different approach to affordable housing. For example, Nordic countries treat the development of low- and medium-cost housing as a public utility. This reduces and stabilizes housing prices by removing the cost of land, construction, finance and management from the speculative market. They have succeeded in producing quality housing that is subsidized and permanently price restricted.

Known as social housing in Denmark, this strategy has produced 20% of the total available housing there.

Given the affordable housing problems in the U.S., taking stock of other options could provide some inspiration.

For PL, the Oakland renter feeling the squeeze of rising rents, as well as for many other full-time workers, the future doesn’t look any better. PL, who is in his mid-50s, told me he doesn’t see a way to retire. He would need to leave his community in order to retire, but he can’t imagine where he would go. The East Bay is his home.

[More than 150,000 readers get one of The Conversation’s informative newsletters. Join the list today.]

Celine-Marie Pascale does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.