The Australian Electoral Commission moved its stall three times to get away from Yes and No campaigners at an Indigenous cultural festival, standing firm in its commitment to political neutrality on the Voice to Parliament referendum.

“They had to be very independent, so every time someone went and sat down next to them they had to keep moving,” Barunga Festival co-coordinator Anya Lorimer told Crikey. “In the end it was three times. I said: ‘You do you; you manage your conflicts and optics and do whatever you need.’ ”

A spokesperson for the AEC confirmed that it did have a roving stall at Barunga Festival earlier this month because Yes and No campaign stalls were in their vicinity a couple of times: “This was done because of our commitment to political neutrality — both real and perceived”.

Moving around had not affected its ability to hand out hard copy enrolment forms to First Nations peoples.

Although decisions to attend events like Barunga Festival were “always made carefully”, the AEC recognised the importance of establishing a regular presence in remote and regional communities, citing feedback from First Nations peoples that in-person attendance (particularly return visits) resulted in increased engagement.

The AEC confirmed that its community engagement teams would be at a number of NAIDOC Week events.

The NT Indigenous voting voice

In the Northern Territory, Indigenous voter enrolment and engagement is at a national low. AEC data shows it’s estimated that 23.3% of Indigenous people in the NT are not enrolled to vote. That’s second only to WA — which registers 25.9% Indigenous non-enrolment — but taking into account miscalculations in census population data due to collection issues in remote communities, NT rates are believed to be higher.

The national Indigenous unenrolment rate is 15.5% (compared with 2.7% for the whole nation), but the AEC told Crikey it had been diminishing year on year and “for the first time” has dipped under 100,000.

The NT has two Australian electoral divisions — Solomon, concentrated in Darwin and surrounds, and Lingiari which spans the rest of the NT. Lingiari has the highest (by far) proportion of Indigenous constituents, with the 2016 census counting 41.7%.

In every federal election since 2001, the Lingiari electorate has consistently registered the lowest (and getting lower) national turnout of enrolled voters. In 2022, 66.83% cast a ballot. That’s down from 72.85% in 2019, which was down from 73.7% in 2016.

Labor member for Lingiari Marion Scrymgour told Crikey the trends were “concerning” and Indigenous enrolment and voter turnout was “not where it needs to be”. She said if the government hoped to improve livelihoods for Indigenous people and bush communities, “it is critical they have a say” in the referendum and the next federal election.

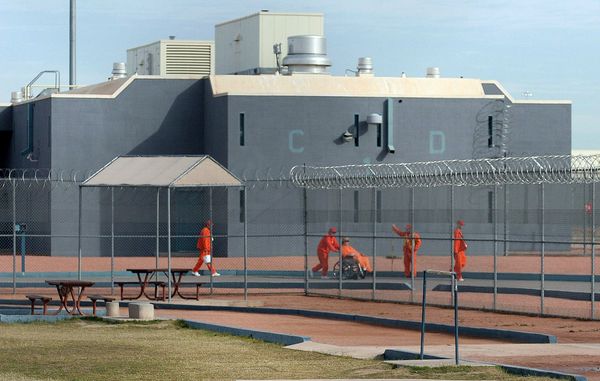

The high proportion of Indigenous prisoners in the NT also sets the territory back with voter enrolment and engagement. The rules are (federally) that anyone 18-plus and serving a full-time prison term under three years is formally part of the compulsory voting Australian cohort. Any prisoner doing time for more than three years is ineligible to vote, although it’s mandatory for that prisoner to enrol.

In the NT, 84% of all adult prisoners are Indigenous, 39% of prisoners have a sentence of three or more years, and from that cohort, 74% are Indigenous.

A spokesperson for the NT Attorney-General and Justice Department told Crikey, that abour 70% of NT prisoners are enrolled to vote, with the AEC trialling an automatic enrolment update program for corrections centres.

Raising the Indigenous vote

After the 2022 federal election, Indigenous enrolment and the Indigenous vote were deemed too low. The Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters declared improvement of First Nations’ ballots — particularly in remote Indigenous communities — to be a priority.

Both the Central and Northern Land Councils made submissions to the committee at the end of 2022 highlighting the need to step up efforts to better enrol and engage Indigenous people in central Australia. They identified the Northern Territory’s Indigenous population — who mostly live in remote or very remote areas — as the most disenfranchised cohort of Australian voters.

In a statement to Crikey, CEO of the NLC Joe Martin-Jard said that eight months later, it’s no secret that Aboriginal people are still underrepresented and there was “work to be done” building equity in electoral enrolment.

He was aware that the AEC was “actively working” to enrol Aboriginal people — particularly in remote areas of central Australia — so they can “have their voices heard”, but would not comment on the effectiveness of these activities.