New York City, United States – Since the start of the Israel-Hamas war, Mohammed — a Cornell University student who asked to be called by a pseudonym — has been careful about attending pro-Palestinian protests.

He always nudges his fellow demonstrators to take precautions: Wear a face mask. Go with a buddy. Remain vigilant.

But it’s not just campus tensions he’s worried about. Mohammed, an aspiring researcher, is concerned that speaking out about the war could imperil his future career goals — and those of his classmates.

“People have been fearful to the point where they don’t want to attend rallies anymore,” Mohammed said. “People are worried about the issue of jobs.”

As demonstrations continue across the United States, protesters rallying for the Palestinian cause have become increasingly uneasy about the professional repercussions they could face for expressing their thoughts.

Those fears have materialised in several high-profile cases. On October 22, a top Hollywood agent resigned from the board of Creative Artists Agency (CAA) amid backlash after she compared Israeli actions to “genocide” on social media.

And on October 26, the editor of the magazine Artforum was fired after he published an open letter from artists calling for “an end to the killing and harming of all civilians”.

But experts say students make up a bulk of new reports of discrimination — and they often have little experience and modest professional networks to fall back upon if they face backlash in their nascent careers.

To Mohammed, the effect has been silencing. He has noticed that his peers “don’t want to be on the front line” and have limited their public advocacy for fear they too could lose professional opportunities.

“I guess that people just thought, ‘Everything we do, we’re always going to be demonised. So what’s the point of talking?’” he said.

Isabella, a PhD student at Harvard University who likewise used a pseudonym to protect her anonymity, said the situation is forcing students to choose between their advocacy and their professional aspirations.

“Any graduate students who support Palestine have to come to a decision on whether or not they’re willing to put their future career on the line before they speak up,” she told Al Jazeera.

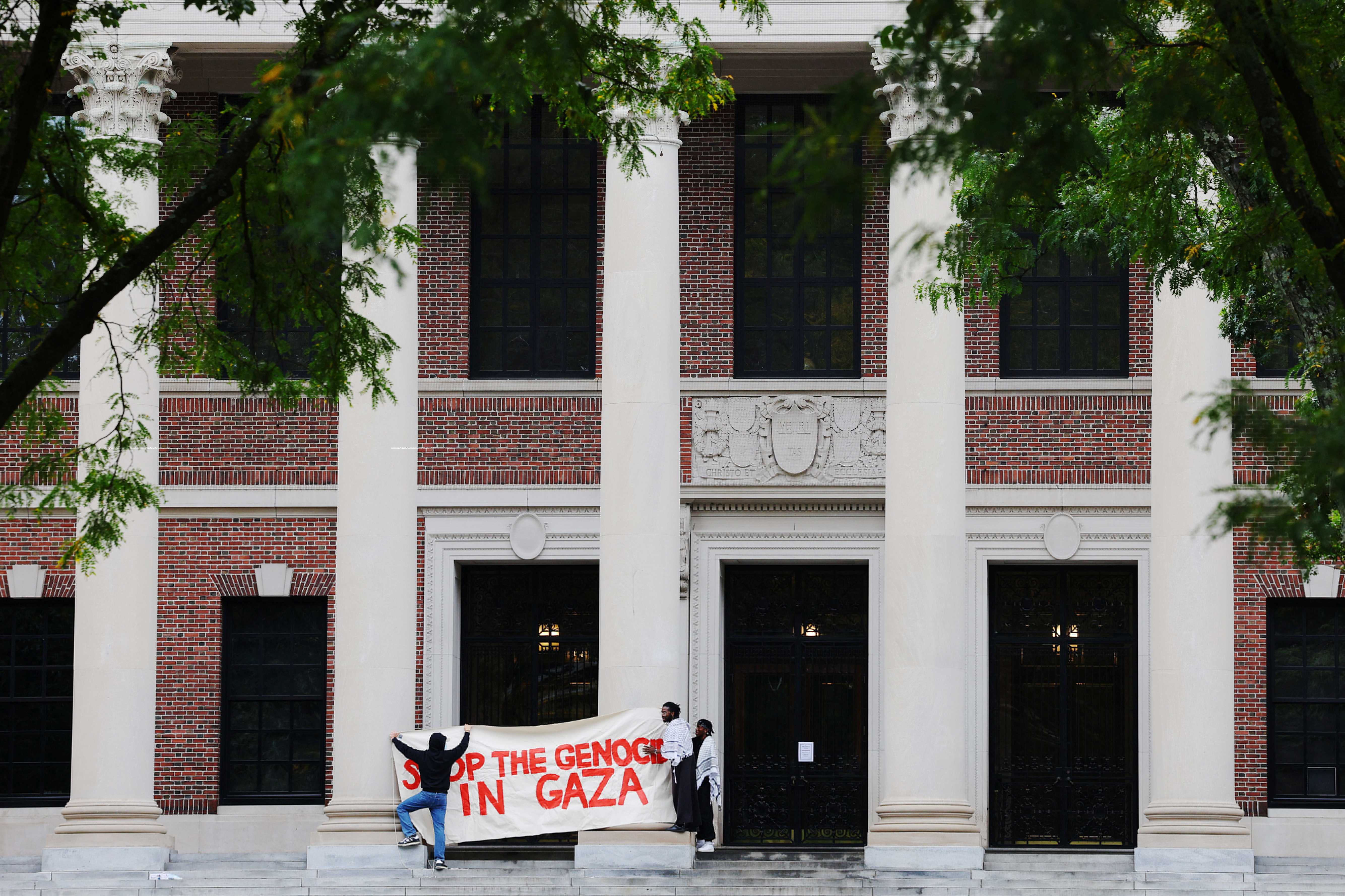

Her campus made international headlines shortly after the start of the war, when 30 student groups signed a letter holding Israel “responsible for all the unfolding violence”.

The letter — released shortly after Hamas launched a surprise attack on Israel on October 7, killing nearly 1,400 people — sparked widespread outcry.

Wall Street executives like hedge fund manager Bill Ackman demanded to know which students were behind the letter so that they could avoid hiring them. Some students were doxxed, a practice by which personal information is shared online to shame or intimidate individuals.

Isabella said that anonymous websites like Canary Mission and the conservative group Accuracy In Media have continued to publish information about pro-Palestinian students.

Accuracy in Media recently parked a mobile billboard truck just outside Harvard’s campus, its screens displaying the names and photos of students allegedly involved with the letter. Above their faces read the title, “Harvard’s leading antisemites”.

Similar trucks have appeared near other Ivy League campuses, including those of Columbia University and Cornell.

Radhika Sainath, a senior attorney at Palestine Legal, a US-based nonprofit, told Al Jazeera that her team has seen an influx of reports from college students who say they are facing discrimination on campus and by employers.

“We’re seeing Palestinian students being threatened with violence and anti-Palestinian and Islamophobic messages,” Sainath said. “They’re getting harassed with death threats, threats to their careers.”

Since October 7, her organisation has received more than 400 complaints through its web platform alone — not counting complaints made directly to its lawyers. Sainath said it is unclear how many students are represented in that total.

Still, the volume of complaints so far dwarfs the total number of complaints Palestine Legal received in the whole of 2022, when it responded to 214 cases.

“People who are taking a principled stance for human rights — who are condemning Israel’s ethnic cleansing of Gaza right now — are being called in,” Sainath said. “They’re being questioned. They’re being fired.”

Baher Azmy, a lawyer at the Center for Constitutional Rights, a progressive legal non-profit, said the workplace climate for students and professionals alike is reminiscent of the period leading up to the Iraq War.

At the time, the attacks on September 11, 2001, had provoked a wave of public grief — and with it, anti-Muslim sentiment, Azmy explained. But there was not “as much of a mechanism to monitor people’s point of view and retaliate against them”.

That has changed with the advent and widespread use of social media.

“That has led to not only concrete reprisals of students, but just a climate of fear and paranoia,” he said.

Azmy also indicates there is very little in the law to prevent employers from making hiring decisions based on what they find online.

Federal law does forbid employers from discriminating based on race, religion, national origin and other factors. Some state laws go even further. In California, for instance, employers are also prohibited from retaliating against employees for their political activities and beliefs.

But as Azmy sees it, the challenge lies with the concept of “at-will employment”, wherein private companies can “largely terminate or withdraw offers” at their discretion. Whether this practice can tip into hiring discrimination is often difficult to prove.

The idea of “blacklisting” students from employment opportunities therefore falls into a legal grey area.

“Conceptually, this constitutes retaliation because of a viewpoint that employers don’t like,” Azmy said. “But it would be challenging to enforce against a private employer.”

Mohammed said he is willing to speak out even if it costs him future opportunities. Still, he requested anonymity when speaking to Al Jazeera.

“You have a truck with pictures of your face on campus. They turn up to our rallies to intimidate people,” he said, referencing the billboard trucks at Cornell. “People are scared.”

But Mohammed remains resolute: No job offer is worth his silence. “I’ve made it very clear,” he said. “There’s nothing you can offer me to be quiet about genocide.”