Larissa was a 21-year-old Canadian college student recovering from COVID-19 when she died from complications related to an accidental overdose of acetaminophen, a medication in probably every drug store and most medicine cabinets in the country.

At the time of Larissa’s death, her sister Darby was a second-year student at the University of Waterloo School of Pharmacy, where we cover this topic in class.

“We were shocked by how fast it happened,” Darby recalled. “Larissa was healthy and within a week of the overdose, her liver failed, she received a liver transplant, and died from complications. We still don’t know what happened. It’s hard because we realize we likely never will.”

Looking back, Darby recognizes that she will never know how Larissa overdosed, except that she did not mean to. It was probably an attempt to treat her COVID-19 symptoms at a time when she was not eating well.

As a liver specialist and pharmacists, we have cared for hundreds of people with acetaminophen overdoses and worked for years to raise awareness of the dangers of both accidental and intentional overdose. The three of us were developing educational tools on acetaminophen-related liver injury for health-care providers when we first learned of Larissa’s story.

Leading cause of acute liver injury

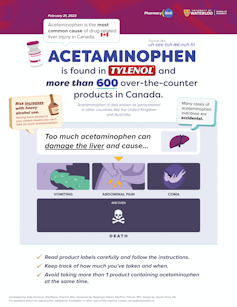

Acetaminophen is in more than 600 products, such as Tylenol, Percocet, Midol, Robaxacet and NeoCitran. Yet, it is also a leading cause of acute liver injury, which can be fatal without a rescue liver transplant. With millions around the world using acetaminophen every day, why are so few people aware of the dangers of overdose?

Approximately 4,500 Canadians are hospitalized from acetaminophen overdose each year — 12 hospitalizations per day. Up to half of overdoses are accidental, which is what Larissa’s family believes likely happened to her.

The risk is highest for people who regularly drink three or more alcoholic drinks daily or who are malnourished or fasting because for them, an overdose can occur at normal acetaminophen doses (for example, the maximum recommended 24-hour dose for adults is up to 4,000 milligrams, and lower in children).

A common error people make is combining over-the-counter and/or prescription drugs that contain acetaminophen. A 2020 survey we conducted also found that over half of respondents were not aware extra strength products contain up to twice the dose of acetaminophen compared to regular strength products.

More recently, the shortage of children’s pain and fever products raised concerns about the risk of accidental overdose in children, as parents and guardians looked to use adult products for their children.

Toxicity and overdose

Lower doses of acetaminophen are not toxic to the liver: most of it is broken down safely by the liver and leaves the body in urine. But the liver has a limited ability to break down acetaminophen.

When too much acetaminophen is taken in a 24-hour period, the liver cannot break it down fast enough. The extra acetaminophen spills over into a back-up pathway in the liver, and the liver breaks the excess down into another product that is toxic to it. The more acetaminophen taken at one time, the more toxic product is made.

In the first 24 hours after an overdose, there may only be mild symptoms such as nausea and vomiting, but many have no symptoms at all.

After one to two days, liver injury begins and symptoms may include abdominal pain, dark coloured urine, and yellow eyes and skin. After three days, symptoms such as bleeding, bruising, confusion and low blood sugar signal that the liver is failing and death can occur.

While the liver may heal itself, around six per cent of people hospitalized for acetaminophen overdose develop liver failure.

Prompt treatment is critical. An antidote is available (an intravenous medicine called N-acetylcysteine) but it is most effective if given within 24 hours of overdose. A rescue liver transplant may be needed, especially if treatment is delayed, and many die waiting for a liver or due to complications after liver transplantation.

Using acetaminophen safely

Given that acetaminophen remains one of the most common medicines for treating pain and fever, people need to take steps to reduce their risk of liver injury.

Start by reading all medication labels. Never take more than one acetaminophen-containing product at a time. Pay close attention to products for arthritis, cold and flu, sleep, menstrual pain and back pain. Do not hesitate to ask the pharmacist for help.

Always check acetaminophen packages for the maximum single dose and 24-hour dose. If the first acetaminophen dose is taken at noon, the 24-hour window ends at noon the next day. Take less if you regularly have three or more alcoholic drinks a day or if you have difficulty eating regularly, such as with an eating disorder, frailty in older age, or during episodes of nausea or vomiting.

When buying acetaminophen for common ailments like a headache or arthritis pain, reach for the regular strength product. Extra strength products increase the risk of accidental overdose.

In the event of an overdose, call Health Canada’s toll-free poison control line (1-844-POISON-X) or your local poison control centre for advice on next steps.

Kelly Grindrod has received research funding from the NSERC PromoScience, Public Health Agency of Canada, Canadian Institutes for Health Research, and the British Academy, and the Canadian Foundation for Pharmacy.

Eric Yoshida is affiliated with the University of British Columbia and the Vancouver General Hospital. He has participated in clinical trials sponsored by Gilead Sciences, Madrigal, Pfizer, Allergan, Celgene, Genfit, Intercept, Novodisc. He has also received an unrestricted research grant from Paladin Laboratories. He has no conflicts of interest with this current article.

Trana Hussaini does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.